Does the Singapore carbon tax help facilitate demand for international carbon credits in Singapore?

The forthcoming amendments to the carbon tax rate(s) set out in the Singapore Carbon Pricing Act 2018 create an arbitrage opportunity for Registered Persons.1

Specifically, Registered Persons will be able to procure and surrender eligible ‘international carbon credits’ at a lower price than the carbon tax rate for an emissions year and if the price of the ICCs in the then-spot market is significantly higher than the carbon tax rate, sell those ICCs and use the proceeds to pay the carbon tax instead.

The Singapore Government should provide further clarity in relation to:

- the eligibility criteria of ICCs (specifically if there will be vintage requirements and what happens mid-way if there is a change in eligibility criteria);

- the role of the new ICC Registry and how ICCs are issued; and

- the process for surrendering ICCs,

so that Registered Persons and market intermediaries who are considering how to structure investments in eligible international carbon credits can proceed with greater certainty.

Disclaimer:

Holman Fenwick Willan Singapore LLP is licensed to operate as a foreign law practice in Singapore. Where advice on Singapore law is required, we will refer the matter to and work with licensed Singapore law practices where necessary.

Introduction

Singapore’s Parliament has passed the Carbon Pricing (Amendment) Act 2022 (the Amendment Act) to amend the Carbon Pricing Act 2018 (the Act). The amendments will come into effect following a notification by the Minister of Sustainability and the Environment2 and are expected to come into operation on 1 January 2024.3 In this paper, unless specified otherwise, a reference to the ‘Act’ refers to the Act as amended.

This paper discusses ‘international carbon credits’ (ICCs), which was introduced as new concept under Singapore law by the Amendment Act.4

The amendment of Singapore’s carbon tax rates is “a key enabler” in Singapore’s Long-Term Low-Emissions Development Strategy which aims to, amongst others, achieve Singapore’s goal of net zero emissions by 2050.5

However, for the market, this development creates an arbitrage opportunity for ‘registered persons’ as defined in the Act (Registered Persons).6 Specifically, Registered Persons may:

- procure and surrender eligible ICCs at a price that is lower than the carbon tax rate for an emissions year; and

- if the price of the ICCs in the then-spot market is significantly higher than the carbon tax rate, sell these ICCs and use the proceeds to pay their carbon tax instead.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the introduction of the ICC scheme has generated both excitement and confusion (as discussed below) amongst Registered Persons. Further, the current lack of guidance on the ICC regime creates uncertainty for market intermediaries who may be considering entering into long-term arrangements in relation to ICCs without the benefit of the interpretative and procedural subsidiary legislation and guidance material.

The key areas of concern for Registered Persons and market intermediaries alike are:

- the criteria for eligible ICCs; and

- mechanism(s) to support or facilitate delivery and surrender of ICCs.

Since 2021, there have been regulatory sandboxes in place for carbon credit projects with“like-minded countries and/or private sector partners in accordance with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement on [ICCs]”.7 These issues may have already been considered by the Singapore Government (the Government) as part of such sandboxes. Nonetheless, clarity on these points will be beneficial so that entities are able to structure their commercial arrangements with greater certainty.

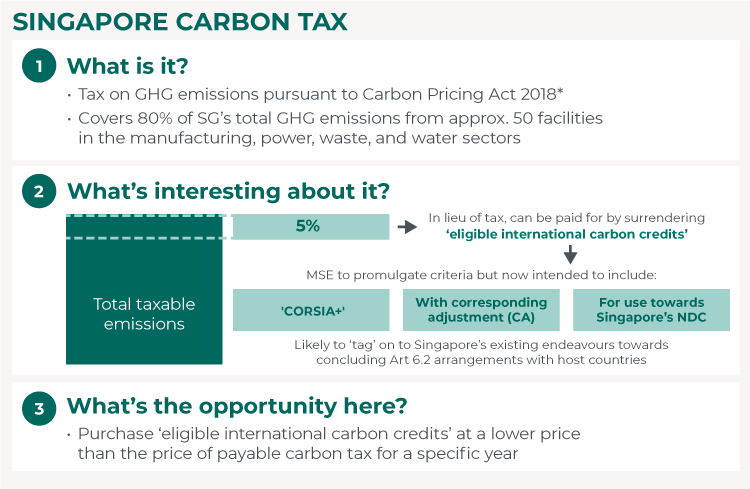

Singapore’s Carbon Tax Scheme

Broadly, under the Act, a carbon tax is “charged on the total amount of reckonable [greenhouse gas (GHG)] emissions” of a business facility8 for a prescribed industry sector that emits 25,000 tCO2e or more GHG emissions in an emissions year. The carbon tax presently covers “80% of [Singapore’s] total GHG emissions from about 50 facilities from the manufacturing, power, waste and water sectors.”

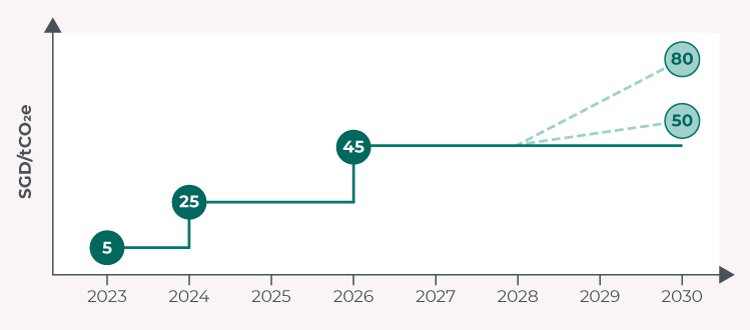

The Amendment Act increases the ‘carbon tax rate’ set out in Part 2 of the Third Schedule to the Act on an incremental basis:

- SGD 5/tCO2e in 2023;

- SGD 25/tCO2 in 2024 and 2025; and

- SGD 45/tCO2 in 2026 and beyond.

However, based on official statements from the Government, the carbon tax rate will increase to between SGD 50/tCO2e and SGD 80/tCO2e by 2030.9

Figure 1: Price Trajectory of Singapore’s Carbon Tax (SGD/tCO2e)10

The existing carbon tax system set out in the original Act had relied on what is now known as a ‘fixed-price carbon credit’ (FPCC). A Registered Person can apply and pay for FPCCs issued by the National Environment Agency (NEA). The Registered Person can then surrender their FPCCs to NEA in lieu of paying the carbon tax which the Registered Person is liable to pay under the Act. The price of FPCCs is set out in Part 2 of the Third Schedule of the Act.

The FPCC scheme will remain broadly unchanged when the Amendment Act comes into force. However, the price of FPCCs will increase, broadly in line with the carbon tax rates discussed above.11

The Introduction of International Carbon Credits

One of the principal changes introduced by the Amendment Act is the distinction between a FPCC and an ICC.

The new ICC regime will work in a similar way to the FPCC scheme in that eligible ICCs can be surrendered in lieu of FPCCs up to a prescribed limit (discussed below). The Registered Person is “treated as having paid the tax to the extent of the carbon price of the [FPCC] that the eligible [ICC] has been surrendered in place of”.12

The Government’s intention appears to be to tap into Singapore’s arrangements with other jurisdictions under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement on ICCs (Article 6.2). For instance, in April 2023 Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong talked about Singapore building “a pipeline of high-quality carbon credit projects to help meet our climate goals”.13 This suggests that the Government may be directly or indirectly financing these projects, purchasing carbon credits on a forward basis to lock in supply, or both. Notably, this willingness to accept Article 6.2-related ICCs does not appear to extend to the other mechanism set out in Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement (Article 6.4 Mechanism) which could have been used to support domestic abatement activity in Singapore without the need to export the Article 6.4 emission reduction internationally.

Figure 2: Snapshot of the Singapore Carbon Tax

*As amended and when in force. Note that the Carbon Pricing (Amendment) Act 2022 was enacted on 10 March 2023 but the provisions have not yet come into force. NEA has said that “[a]ll the legislative amendments will come into effect on 1 January 2024”: https://www.nea.gov.sg/our-services/climate-change-energy-efficiency/climate-change/carbon-tax

What is an ‘international carbon credit’

An ICC is“a certificate representing one tonne of GHG emissions reductions or removals measured in tCO2e, generated from any project or programme outside Singapore”.14 There are two key elements to this definition:

| Element | Significance |

|---|---|

| It is a certificate15 representing 1tCO2e of GHG emissions reductions or removals | The Government is not limiting ICCs to just one of ‘reductions’ or ‘removals’ and the definition explicitly includes both reductions and removals. |

| It relates to a project or programme outside Singapore | What this means is that a GHG emission reduction or removal project in Singapore, e.g., a VCS or Article 6.4 Mechanism project relating to a GHG emission reduction activity in Singapore will not be accepted for the purposes of the ICC scheme. The Government’s reasoning is not entirely clear but appears to be linked to Singapore’s economy-wide nationally determined contribution (NDC) and perhaps a presumption that the cost of domestic abatement in Singapore would preclude the economic viability of the reduction or removal activity in Singapore. It therefore appears that the Government is seeking to use eligible ICCs towards its NDCs following Art 6.2 arrangements with host countries. |

The Act is silent on how ICCs will be issued. Section 33D provides that the NEA can“establish, maintain and manage” an ‘International Carbon Credits Registry’ and “open and close ICC registry accounts for registered persons in such registry for purposes connected with the surrender of eligible international carbon credits in place of fixed price carbon credits in connection with the payment of any tax under [the] Act” [emphasis added]. On 4 July 2023, Minister Grace Fu confirmed that the Government was “working on the establishment of an ICC registry”.16

What remains unclear, is whether ICCs will be issued by the newly created ‘International Carbon Credits Registry’ (ICC Registry) and transfers will have to be made within the ICC Registry’s infrastructure, or if ICCs would be issued by an existing voluntary carbon standard registry.

The former option appears unlikely at present:

- debates in Parliament on the memoranda of understanding with Verra and Gold Standard suggest that ICCs would, in the first instance, be issued by a separate carbon standard registry;17 and

- unlike FPCCs18 there is no section in the Act which deals with the crediting of ICCs (though this may be addressed in subsidiary legislation).

We discuss this point in further detail below (see Surrender), but a lack of clarity here will affect delivery and offtake arrangements.

Eligibility

Pursuant to section 33A of the Act, an eligible ICC:

- “meets the prescribed criteria”; and

- “is acceptable as an eligible international carbon credit by [NEA] in accordance with any direction of the [Minister for Sustainability and the Environment]”.19

The prescribed criteria and directions will be set out in subsidiary legislation.20

Eligibility: what we know so far

Eligible ICCs will be ‘CORSIA+’.

Minister Grace Fu indicated in November 2022 that the ICC criteria will “minimally reference the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation” (CORSIA) as“[t]hese are a set of environmental integrity standards that have been developed and backed by a multilateral process led by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), in consultation with green groups and experts, and are widely regarded as some of the most rigorous in the industry.”21

However, Minister Grace Fu has also advised that “[a]s the market for carbon credits is nascent and growing, [Singapore] will review [the] eligibility criteria periodically to align with developments” so there may be changes over time (as we discuss further below).

In February 2023, following certain news reports on Verra, Minister Grace Fu advised Parliament that the Government intends to ensure that the ICCs used for the carbon tax would “uphold high environmental integrity standards” and a “whitelist of acceptable [international carbon credits]… which will include eligible host countries, carbon crediting programmes and methodologies”22 will be published later in 2023.

In summary, the eligibility criteria will use CORSIA as the starting point23 but introduce additional requirements, e.g., excluding certain methodologies or types of projects or programmes24, and limiting the list of eligible host countries (initially to those that Singapore has an Article 6.2 arrangement with for example, but once the Article 6.4 Mechanism is operational, this may be expanded to other countries).

Eligible ICCs will likely have to be authorised for corresponding adjustment and use towards Singapore’s NDC

In our view, it is likely that eligible ICCs will have to be authorised for corresponding adjustment and use towards Singapore’s NDC.

Although this is not expressly stated in the Act or Parliamentary reports, Minister Grace Fu has expressly stated that surrendered eligible ICCs will need to be “compliant with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement”25 which suggests that the requirements for internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) under Article 6 would have to be satisfied.

In our view, these elements are (i) the de minimis requirements under the Article 6.2 guidelines agreed under the Paris Agreement, and more importantly (ii) corresponding adjustment and NDC use authorisation. This is because the carbon tax relates, ultimately, to Singapore’s emissions and accordingly Singapore’s obligations in relation to its NDCs under the Paris Agreement. For every tCO2e that exceeds Singapore’s committed NDC level (a ‘+1’),26 Singapore would have to procure a reduction or removal (a ‘-1’) to cancel out such excess and ensure that Singapore can meet its NDC. Recognising that Singapore is an “alternative energy disadvantaged” country, the Government stated in the Second Update to its First NDC that it “will also pursue opportunities to leverage international cooperation under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. This includes the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs)”.27 As Minister Grace Fu noted, with the finalisation of the Article 6 rulebook and countries now able to “cooperate through carbon markets to mutually support their respective climate targets… Singapore is keenly exploring… new possibilities”.28 Therefore, it seems likely that Singapore will wish to ensure that eligible ICCs qualify as ‘ITMOs’ for use towards Singapore’s NDC.

Figure 3: List of Memoranda of Understanding or Letters of Intent relating to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement as publicly announced by the Government (as at 22 August 2023)

| Jurisdiction/Host Country | Date Announced |

|---|---|

| Ghana | 15 November 2022 |

| Morocco | 7 July 2022 |

| Peru | 21 November 2022 |

| Colombia | 3 August 2022 |

| Vietnam | 18 October 2022 |

| Thailand | 14 October 2022 |

| Papua New Guinea | 16 November 2022 |

| Mongolia | 9 June 2023 |

| Indonesia | 21 March 2022 |

| Dominican Republic | 27 June 2023 |

| Cambodia | 26 April 2023 |

| Kenya | 1 May 2023 |

| Bhutan | 18 May 2023 |

| Chile | 14 August 2023 |

| Sri Lanka | 22 August 2023 |

Eligibility: the unknown

What yet has the Government to confirm in relation to eligibility?

- Vintage of eligible ICCs. To the extent that Singapore intends to use eligible ICCs towards its NDCs, will there be limitations on the vintage of eligible ICCs? Based on present guidance for Article 6.2 and Article 6.4, the earliest vintage will be 2021. Whilst the Government has only projected the position up to 2030 (which is the date of its first NDC, as revised), the carbon tax regime under the Act extends beyond 2030 and depending on the type of project in question and the voluntary carbon standard, ICCs from such projects with crediting periods starting today may be generated beyond 2030. Registered Persons purchasing on a forward basis will welcome clarity on this point so as to better structure their commercial arrangements.

- What happens if there is a change in eligibility criteria? Long term offtake agreements may procure ICCs from a specific project on the basis that each ICC issued in respect of it is (on day one) an eligible ICC. There is investment risk if an ICC could become ineligible during the term of a forward purchase arrangement (e.g., due to quality concerns but at no fault of the project or its developer and/or if the Government unilaterally decides that a project’s methodology is no longer eligible under the ICC scheme). In such a situation, and if the Registered Person’s sole interest in ICCs was for the purposes of its compliance obligations under the Act, the ICCs would no longer be fit for purpose. Such Registered Persons would want some assurance on the usability of such ICCs prior to taking on such long-term commitments. Clarity from the Government for such circumstances would be most welcome from all quarters.

The prescribed limit

Pursuant to section 33B(1) of the Act, the total number of eligible ICCs cannot exceed the ‘prescribed limit’, which we expect will be confirmed via subsidiary legislation.

The figure of 5% of taxable emissions has been touted as the limit which is under consideration. As noted by the National Climate Change Secretariat:29

The facility-level limit has been set at 5% to ensure that the industry continues to prioritise domestic emissions reduction, while providing an additional decarbonisation pathway for hard-to-abate sectors that may find it challenging to significantly cut emissions in the near to medium term. This limit is aligned with other comparable jurisdictions with similar climate ambitions, such as South Korea and California. We will continue to review the facility-level limit over time to align with international developments.

In November 2022, Minister Grace Fu acknowledged that this number was the ‘start’ and that “as the market develops, [Singapore] will see how it goes and [it] will make changes along the way”.30

Further, the Act provides that the Minister for Sustainability and the Environment can permit eligible ICCs to be “surrendered in excess of the prescribed limit in any particular case or class of cases”31 – thus potentially allowing flexibility in respect of certain industry sectors or participants. This power is distinct from the transitory allowances which ‘Emissions-Intensive Trade-Exposed sectors’ are permitted under Division 1A of Part 5 of the Act.32 These allowances are deducted directly from total taxable GHG emissions for the purposes of calculating the carbon tax payable by a Registered Person.33

As at 17 August 2023, there are no public announcements to that effect and it therefore does not appear that the Minister’s power to permit excess surrenders will be utilised when the Amendment Act comes into force.

Surrender and Delivery of eligible ICCs

This is the least clear part of the Act but, in our view, is a crucial aspect of the ICC scheme, at least for the purposes of structuring transactions. Determining what ‘surrender’ amounts to, and how it might be effected, are key aspects of how the market will approach delivery mechanisms as between a Registered Person (as buyer) and a project developer or intermediary (as seller).34

As discussed above, an eligible ICC can be surrendered under the Act in lieu of a FPCC up to a prescribed limit.35 However:

- ‘Surrender’ is not defined in the Act; and

- The precise mechanics of surrender are unclear. Unlike the FPCC regime in the Act,36 the Amendment Act is silent on the surrender process for eligible ICCs.

As discussed above, an ICC Registry may be set up (i.e. ICC Registry accounts for Registered Persons will be created by NEA for the purposes of ICCs).37

The surrender process may be more logically and appropriately dealt with as part of subsidiary legislation and guidance38 if the eligible ICCs are issued initially by a third-party registry as opposed to a registry set up by NEA. For instance, most projects are presently developed under one of the voluntary carbon standards (e.g., the Verified Carbon Standard). After the GHG emission reductions or removals are verified to the administrator’s satisfaction, units are then usually issued to a registry linked to the standard (e.g., the Verra Registry in the case of the Verified Carbon Standard). Transfers of units occur within and pursuant to that registry’s framework and process requirements. The rules of that third-party registry determine the transfer/delivery process. Advisers in the voluntary carbon market will be familiar with this.

It is likely that for ICCs there will be two parts to the delivery process – from a project developer or intermediary to the Registered Person, and from the Registered Person to the NEA.

During the first part, deliveries may operate as per what is presently done for existing voluntary carbon market deliveries.

However, during the second part of the process, given that the Registered Person is seeking to satisfy its compliance obligations, delivery and (subsequently) surrender need be done in accordance with the Act. In the context of FPCCs, surrendered FPCCs are removed from the Registered Person’s account in the FPCC Registry. Taking the same approach to ICCs held in voluntary carbon standard registry accounts may present certain difficulties, for the reasons discussed above.39 Further, to the extent that the Registered Person needs to deliver the eligible ICCs to Singapore’s ICC Registry,40 how delivery and surrender will be effected, in practice, needs to be clarified in subsidiary legislation.

For completeness, under many existing voluntary carbon market documentation, delivery of the carbon units may (subject to the rules of the voluntary carbon standard) be done by way of ‘retirement’. In other words, the carbon units are retired by the seller for the benefit of a person designated by the buyer. We query whether this is workable under the Act. It is not clear whether ‘retirement’ of an eligible ICC by a Registered Person (or a market intermediary on behalf of the Registered Person) with the ‘use case’ being compliance or ‘retirement’ for use by the Government for NDC purposes41 would be consistent with the terms of the Act (unless supplemented by relevant drafting in the much anticipated subsidiary legislation). Ultimately, given the compliance obligations which Registered Persons must meet, the delivery/surrender process for ICCs must comply with the Act. The process must also be workable and cost-effective if the ICC regime is to succeed. Given market interest in ICCs and the opportunities offered by the forthcoming changes to the Act, it would be useful if the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment could clarify the ICC surrender process.

Conclusion

The Act (as amended) presents opportunities for Registered Persons and market intermediaries. However, clarity in respect of:

- eligibility criteria (specifically if there will be vintage requirements and what happens mid-way if there is a change in eligibility criteria);

- the role of the new ICC Registry and how ICCs are issued; and

- the process for surrender of ICCs,

would be welcome.

Other issues, such as how any Article 6.2 framework agreed by the Government and a host country might deal with the involvement of a market intermediary (in particular, an entity incorporated outside Singapore), how an authorisation framework may work, and whether a market intermediary should (or, indeed, could) have investor protection under such a framework, are outside of the scope of this paper but should be explored as part of the structuring of any transactions relying on such Article 6.2 frameworks.

These issues will impact how Registered Persons and market intermediaries will structure their investments in eligible ICCs for the purposes of the Act.

The market is alive to these questions and Registered Persons and market intermediaries are considering the form that their long-term offtake plans for ICCs may take. Given market interest in ICCs and the opportunities offered by the forthcoming changes to the Act, it would be useful if the Government could clarify how they intend the ICC regime to work in practice and provide greater investment certainty for market participants.

Footnotes:

- Defined below.

- Section 1 of the Amendment Act. As of 17 August 2022, no such notification has been issued by the Minister.

- National Environment Agency, “Carbon Tax”: https://www.nea.gov.sg/our-services/climate-change-energy-efficiency/climate-change/carbon-tax [NEA Carbon Tax]: “All the legislative amendments will come into effect on 1 January 2024.”

- Other aspects of the Amendment Act, which include an updated list of greenhouse emissions and their global warming potential values, are beyond the scope of this paper.

- National Climate Change Secretariat, 4 November 2022 “Singapore’s Long-Term Low-Emissions Development Strategy”: https://www.nccs.gov.sg/media/publications/singapores-long-term-low-emissions-development-strategy/.

- At a risk of oversimplification, a Registered Person is a person who is obliged to register as a ‘registered person’ under the Act for a business facility that is a subject of the Act and thus obliged to pay the carbon tax.

- Ms Grace Fu, Hansard, 4 July 2023, Parliament No. 14, Session No. 2, Volume 95, Sitting No. 106, “Regulatory Sandboxes for Small-Scale Carbon Offsetting Projects”: https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/sprs3topic?reportid=oral-answer-3268 [Sandbox Debate].

- Being a single site at which any activity or series of activities (including ancillary activities) that involves the emissions of greenhouse gas and forms a single undertaking or enterprise, having regard to any circumstances prescribed under the Act: see sections 2 and 3 of the Act.

- See e.g., “with a view of reaching [S]$ 50 to [S]$ 80 per tonne by 2030“: NEA Carbon Tax.

- Once the amendments in the Amendment Act are in force. The pricing trajectory from 2029 to 2030 has not legislated: see footnote 7 above.

- Note that while the Government has suggested that the pricing will be adjusted from 2028 onwards, the Act itself presently states that the carbon tax etc. for 2028 onwards would be SGD 45. Consequently, further legislative amendments will be necessary in order for the projected Singapore carbon tax price to be further increased.

- Section 33B(3) of the Act. See also section 17(3A) of the Act.

- Deputy Prime Minister, Mr Lawrence Wong, Hansard, 10 April 2023, Parliament No. 14, Session No. 2, Volume 95, Sitting No. 96, “Prime Minister’s Office (Strategy Group) (Addendum to President’s Address): https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/sprs3topic?reportid=president-address-2151.

- Section 2 of the Act.

- As an aside, a registry responsible for the issuance of voluntary carbon credits may not construe such a credit as a ‘certificate’ and may use more generic language. The impact of this, if any, is outside the scope of this paper.

- Sandbox Debate.

- Ms Grace Fu, Hansard, 7 February 2023, Parliament No. 14, Session No. 1, Volume 95, Sitting No. 82, “Due Diligence on Carbon Credits Issued by Gold Standard and Verra”: https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/sprs3topic?reportid=oral-answer-3037 [Due Diligence Debates]. For instance: “The MOUs are not legally binding and do not qualify all ICC issued by Gold Standard and Verra, as companies must meet the environmental integrity criteria of the Singapore Government” [emphasis added].

- Section 27 of the Act.

- Section 33A of the Act; see “Minister” in Section 2 of the Act.

- Ms Grace Fu, Hansard, 8 November 2022, Parliament No. 14, Session No. 1, Volume 95, Sitting No. 74, “Carbon Pricing (Amendment) Bill”: https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/sprs3topic?reportid=bill-600 [Carbon Amendment Bill Debates].

- Carbon Amendment Bill Debates.

- Due Diligence Debates.

- It is not clear whether this is CORSIA Pilot Phase or CORSIA Phase One, but this is likely CORSIA Phase One due to vintage and corresponding adjustment requirements.

- Singapore has signed MOUs with, amongst others, Verra, Gold Standard, GCC, ART and ACR. Contrast that to the list of registries which are presently eligible or have in-principle approval from CORSIA for CORSIA phase one.

- Carbon Amendment Bill Debates.

- And to the extent that Singapore intends to meet its NDC.

- UNFCCC, “Singapore’s Second Update of its First Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and Accompanying Information”.

- Carbon Amendment Bill Debates.

- See National Climate Change Secretariat, “Carbon Tax”: https://www.nccs.gov.sg/singapores-climate-action/mitigation-efforts/carbontax/ [NCCS Carbon Tax].

- Carbon Amendment Bill Debates.

- Section 33B(2) of the Act.

- For how they are determined, see NCCS Carbon Tax.

- Interestingly (and mostly for legal geeks), the entire section on such allowances is subject to the purview of the Minister for Trade and Industry and not the Minister for Sustainability and the Environment. As Minister Grace Fu explained, “Similar to our corporate income tax framework under the Economic Expansion Incentive (Relief from Income Tax) Act 1967, the industry transition framework will be administered by the Minister for Trade and Industry, who can assign relevant functions and powers to an appropriate public body”: Carbon Amendment Bill Debates.

- For instance, if delivery of eligible ICCs by way of retirement is subsequently deemed to be acceptable.

- Sections 17(3A) read with section 33B of the Act.

- Section 28 of the Act.

- Section 33D of the Act.

- E.g., subsidiary legislation pursuant to Section 33D of the Act.

- There may be a need to consider sub-account structures in the context of the registry’s architecture and agreements between the third party registry and NEA but this is outside the scope of this paper.

- E.g., to account for requirements under the Article 6.2 guidelines – though these have not been fully decided.

- E.g., Gold Standard has presently used “Singapore” as a test case in their Article 6 guidance material for their registry, including retirement for ‘compliance’ use case by ‘Singapore’.

-1024x683.jpg)