There may be an assumption that tokenisation is the only way to achieve fractionalisation of the ownership of real-world assets – and, specifically, commodity products.

As we discuss in this paper, it is possible to fractionalise commodities off-chain, i.e. in a manner which does not rely on distributed ledger technology or blockchain solutions. So, what factors influence the legal structure that is applied to underpin the fractionalised solution, whether on-chain or off-chain? We consider those factors in this paper.

The fractionalisation of a commodity refers to creating smaller, more affordable fractions in a single unit of a particular physical commodity – a gold bar, for example – by notionally dividing it into shares that can be bought and sold by multiple stakeholders. This is often referred to as creating ‘fractional ownership’.

Whether that ‘ownership’ gives legal title in the commodity to the holder of the fraction, or whether it gives the holder something else, depends on the legal structure that is adopted to underpin the fractionalisation. This may, or may not, be tokenisation. To be clear, although fractionalisation is often cited as one of the benefits that arise from tokenisation of a commodity, as we discuss below, tokenisation is not the only way in which fractionalisation can be achieved, as a matter of law. There may be other legal structures that can be implemented to achieve a similar legal or commercial outcome, such as, an undivided interest in the commodity.

We are seeing an increased interest in finding ways to fractionalise commodities, often on the back of distributed ledger technology (DLT) through the issuance of tokens.

One of the biggest drivers for this arises from the opportunity to enhance market access to commodities, as an investable asset class, to private investors (as opposed to major institutional investors). This class of private investors may include retail investors, but perhaps is more accurately targeted at small to medium sized companies (SMEs) looking to diversify their exposure to different asset classes.

“Fractional ownership may allow for more inclusive access of small and retail investors to somehow restricted asset classes, while enabling global pools of capital to reach parts of the financial markets previously reserved to large investors.” – OECD (2020), The Tokenisation of Assets and Potential Implications for Financial Markets, OECD Blockchain Policy Series1.

It is worth noting that fractionalisation, as a concept, is not novel. In the context of attracting investment into financial products, the sale of units in an exchange traded fund (ETF), mutual fund or real estate investment trust are ultimately all existing examples of fractional investment opportunities. This paper, however, focuses specifically on commodities, distinct from other real-world assets. We note that there have been ETFs of many classes of commodities, including baskets of commodities. However, ETFs fall within the bucket of products targeted at institutional investors because they remain in a highly regulated space.

Investment in commodities has always been seen as more challenging due to their physical nature, real-world application, and distinct features that vary from commodity to commodity. For example, natural gas and soymeal cannot be stored in the same way, and nor can electricity and crude oil be transported in the same way. These differential features of commodities, requiring expertise to supply, manage, transport and store, is the reason specialist commodity businesses have developed by category, such as ‘oil majors’, ‘mining majors’, ‘agri-majors’, etc., and big commodity traders develop specialist desks for trading particular products.

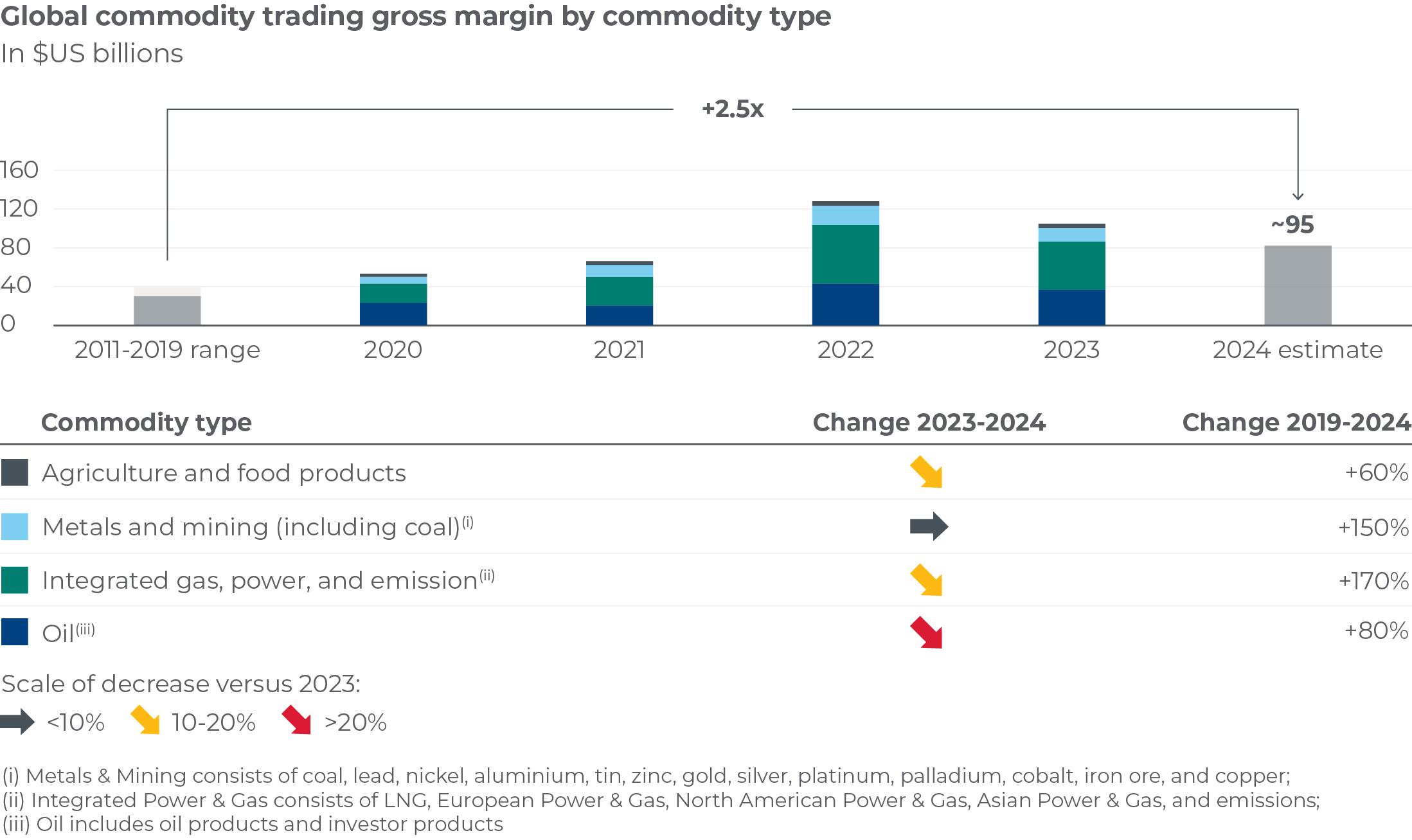

Notwithstanding this, as the data compiled in the table below about the gross trading margin of commodities2 shows, the rate of growth across different commodities sectors over the past five years, is too important for investors to ignore. The growth of gross trading margin in the metals and mining sector alone has been 150% between 2019 and 2024. To date, the benefit of such opportunities has been limited to institutional investors, specialist commodity majors and traders. The business case, therefore, to open up commodities to a wider category of investors is obvious.

Source: Christian Lins, Adam Perkins, Alexander Franke, and Marc Zimmerlin, Ushering in a New Era For Commodity Trading Growth, in BALANCING ACT: A NEW BASELINE FOR COMMODITY TRADING GROWTH (Oliver Wyman).3

“It’s about reimagining the whole end-to-end process of finding and matching investors with investment opportunities, and the subsequent secondary market opportunities once an investment has been made. There are potentially new opportunities on both the supply and demand side.”

Mark Whitman and Antony Lewis, Asset Fractionalisation – What, Why, and the Future (2019)

In the context of the benefits of tokenisation, it is often said that, in theory, any recognised, discernible unit of a particular commodity can be tokenised and, therefore, fractionalised. This may be true as a general remark but once you consider the features or characteristics of the underlying commodity, it becomes clear that some commodities are more suitable than others for fractionalisation.

Gold bars are often cited as an example of a commodity that can be fractionalised. A single LBMA ‘loco London’ gold bar, at roughly 430 fine ounces, is presently valued at over US$ 1 million. This high cost per bar means that only institutional investors or high net worth individuals can access gold as an investment. However, fractionalising rights to that bar enables multiple investors to be exposed to gold as an investment class, thanks to the lower price of entry, thus democratising access to such commodities investments. Further, gold does not have an expiry date and although it must be stored securely, it does not require a high degree of maintenance. By way of contrast, agricultural products such as coffee beans, which should not be stored for more than a year, do not allow for anything more than short-term fractionalised investments. Carbon offset units, representing a claim that 1 tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) has been reduced or removed, cannot be easily fractionalised without causing traceability and evidentiary challenges associated with multiple retirees of the very same tonne of CO2e.

Often the provider of the fractionalised solution does not have the requisite expertise associated with the specific commodity category. This too can be a limiting factor in what the fractional solution provider is capable of fractionalising. As we discuss further below, in the context of on-chain tokens that are backed by a commodity, trust in the person looking after the commodity, as the bridge between the on-chain world and the off-chain world, becomes paramount to the confidence that can be placed in the commodity token. For ease of reference, in this paper, reference to ‘off-chain’ means “actions or transactions that are external to the distributed ledger or blockchain”, and ‘on-chain’ refers to, “actions or transactions that are recorded on the distributed ledger or blockchain”4.

There are many benefits of fractionalisation beyond democratising access to certain types of commodities. We highlight some of these benefits in the table below.

| No. | Particulars | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 24/7 trading and real-time settlement producing capital efficiencies for participants in the trade | Traditional commodity trading markets operate on schedules dictated by global exchanges and settlement systems for payments. Tokenised commodities liberate the trading of commodities from scheduling constraints, allowing for the instantaneous transfer of ownership of the (interests in) commodities, regardless of the time of the day or the geographic location of the parties. With the right application and legal analysis in the clearing jurisdiction where such technology is implemented, it could reduce counterparty risks, free-up collateral and produce capital efficiencies for the participants in the trade. |

| 2. | Removes frictional costs in transacting and transparency | Depending upon the fractionalisation structure used, e.g. whether through tokenisation or the use of undivided interests (see below), one can expect a reduction of frictional costs compared to the traditional form of commodity transaction. This arises through factors such as: (a) economies of scale where the intermediary costs are absorbed significantly by the central agency and distributed amongst all investors of a class; (b) reduction of the number of intermediaries involved whereby the multiple third-party functions are consolidated into more efficient structures; or (c) disintermediation, that is, replacement of human-centric services with automated protocols. In contrast to the traditional costs of transfer which may involve frictional costs (for instance, for brokerage), the cost of an on-chain transfer of a fractionalised and tokenised commodity may just be a few cents, depending on the chosen blockchain. The on-chain solution also comes with an ancillary benefit, in that it allows for transparency of ownership records by providing a verifiable record of every transaction. The immutable ownership chain which can be created by DLT and viewed either publicly (for a public blockchain) or privately can serve as an indicator of who holds title in the token and the underlying commodity. Such traceability is valuable for commodities where authenticity in ownership chain is critical. |

| 3. | Automated functionality in smart contracts increases efficiency | Using DLT, functionalities built into the smart contracts facilitating the fractionalisation, such as codes which are automatically executed upon pre-defined conditions being met, can optimise the transaction process. For instance, a smart contract could be programmed to release funds to a seller automatically upon the specific quantity of fractionalised (interests in) commodities being verifiably delivered to the buyer’s digital account. |

| 4. | Unlocking greater liquidity | By removing the price entry barrier on commodities, fractionalisation expands the pool of potential buyers for the commodities. When this is coupled with the ability to transact round the clock, fractionalisation inherently creates a more active and dynamic market. The benefits are compounded with more accurate price discovery on account of the price of the asset being determined by real-time demand and supply. This is particularly beneficial for commodities that are otherwise illiquid. |

Despite its many benefits, fractionalisation comes with its own challenges. We discuss some of these challenges below:

| No. | Particulars | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Exposure of retail customers to financial products | Historically, most financial instruments have been out of reach to retail customers unless offered by or through regulated market intermediaries. Commodity products such as derivatives or futures in commodities are regulated instruments meaning that access to commodity price exposure has been subject to regulatory supervision. Fractionalisation, with a view to increasing access to retail and SME audiences, cannot be at the expense of the protections otherwise afforded to retail investors by regulatory frameworks. Compliance with the relevant regulatory frameworks becomes paramount to ensuring the success of the fractionalised commodity product. However, this is harder to do in the context of permissionless networks. For example, ensuring that anti-money laundering laws (AML) and counter-financing of terrorism (CFT) requirements of a particular country are met is more difficult to achieve where there is no ‘single point’ of contact to apply such regulations to, and where tokens may be traded on a decentralised token exchange by anyone with access to a simple piece of computer code. In this context, technology may also provide the solution, through the use of “permissioned” protocols. Such protocols restrict access to certain whitelisted participants that have satisfied regulatory requirements, including specific ‘Know-Your-Customer’ (KYC) regulations that might otherwise be applied to centralised markets. Other solutions may involve the use of ‘zero knowledge proofs’.5 |

| 2. | Real-world connectivity | Unlike some pure decentralised finance products, where the connection of the token to the physical world is minimal, commodity-backed tokens representing physical, real-world assets, cannot avoid that connection. This is because the underlying commodity, against which the token is issued, has to be stored, maintained and ideally capable of being either delivered or sold, in order to deliver up a cash value equivalent. This is also true of other fractionalised solutions that are not token based. This necessitates the role for a ‘gatekeeper’ to manage the commodity. We use that neutral term deliberately, rather than ‘custodian’, ‘trustee’ or ‘bailee’, each of which denotes a specific legal relationship between the person possessing or controlling the commodity, and the ‘notional’ owner of the commodity (whether via a token or undivided interest). The holding structure may vary based on the market practices of the specific commodity in question, or the laws of the jurisdiction where the commodity is held. Warehouses, vaults and storage tanks often work on the basis of a bailment model, but variations on these themes include custodial frameworks or arrangements where the ownership is vested in a trustee. |

| 3. | Regulatory and cross border enforcement | The laws around how tokenised products are regulated are not globally harmonised. In particular, in the context of on-chain commodity products on a public blockchain, managing the regulatory perimeter that applies to the token becomes much more challenging given the inconsistency in cross-border regulatory frameworks. This can lead to regulatory arbitrage increasing the risks for retail customers. Legal uncertainty in some jurisdictions, relating to whether commodity-backed tokens are recognised as property under private law, can lead to doubts as to whether they can be owned or not. Legal uncertainty can also follow in respect of smart contracts written in code, and whether they are enforceable in the same manner as traditional contracts under the private law of the relevant jurisdiction. These are not issues in jurisdictions such as Singapore and England where laws or jurisprudence around smart contracts has been articulated but, absent universal adoption of such rules, this can inhibit the wider use of such fractionalised solutions. Writing the applicable governing law and choice of jurisdiction that is intended to apply to the commodity-backed token into the code of the smart contract can help with determining the applicable law and the forum for airing any disputes. |

| 4. | Redemption of the fractional interest | A key feature of the fractionalised commodity-backed asset is the ability to redeem that interest and take delivery or possession of the underlying commodity. In the context of smart contracts built into the fractionalised unit, the speed of redemption or settlement is considered a key advantage of the use of DLT. However, it cannot be assumed that redemption means physical delivery, or possession, of the underlying commodity. For example, in the case of the HSBC Gold Token issued in Hong Kong dollars using a private ledger structure, the token holder is ultimately ‘cashed out’ and no physical gold is deliverable. The role of the commodity ‘gatekeeper’ (see above) in facilitating redemption, is the bridge between the on-chain world and the off-chain world. However, if the underlying commodity has been stolen, destroyed or damaged while in storage, essentially the value of that fractional interest can be worthless. The importance of a ‘trusted’ gatekeeper to verify the authenticity, quality, quantity and provenance of the commodity, cannot be underestimated. This necessitates scrutiny and due diligence of the issuer of the token, and the ‘gatekeeper’, where they are different persons. The redemption of the commodity is also an important driver in the choice of commodity to be fractionalised and the legal structure that underpins it. For example, the Pax Gold token, representing one fine troy ounce of a London Good Delivery gold bar stored in vaults in London, gives the token holder fractional ownership of a part of a whole bar. This could lead to a result where a “customer could hold fractions of several different bars …“,6 so where a customer does not own enough tokens equal to a full gold bar, its stake in a gold bar is pro-rated. Redemption, by taking delivery of the gold bar, is only therefore possible and permitted where the customer holds at least 430 ounces of Pax Gold (i.e., a whole London Good Delivery gold bar). Abaxx Spot’s off-chain product allows holders to redeem their undivided interest through physical delivery on a single 1 kilo bar of gold, essentially lowering the bar for physical delivery of gold, compared to Pax Gold. |

| 5. | Interoperability between the on-chain world and off-chain world | Fractionalisation, when channelled solely through tokens, is premised on the creation of a unified, global marketplace. The reality, however, is that it could give rise to fragmentation of the market for the same commodity, if the commodity’s tokens are traded on-chain in a manner that is not interoperable with the off-chain physical market, splitting the market into two distinct pools and creating grounds for price arbitrage. Whereas fractionalisation is a benefit that may create liquidity for an illiquid physical commodity asset, the flipside is that it can bifurcate the price discovery of a liquid physical asset by fragmenting the on-chain market from the off-chain market. Further, where there is an absence of interoperability between the on-chain and off-chain commodity products, a delinking of the token price can occur from the underlying asset in traditional markets.7 |

An undivided interest in respect of a commodity is a proportional ownership of that commodity, held within a bulk. Both English common law and the (UK) Sale of Goods Act 1979 recognise the ability for an ownership interest to arise in the context of the sale of goods held in the form of a bulk (or within a fungible pool of a commodity). Besides just recognising the title to the goods, the law also recognises the owner’s ability to transfer its title (essentially, its undivided interest) in the goods under a sale and purchase arrangement.

In the context of choosing legal structures for fractionalising commodities, the “undivided interest” provides an important alternative to support the fractional right-holder’s relationship with the commodity. It allows the commodity stored (for example, in a warehouse, tank or vault) to be fractionalised in proportion to the owner’s interest in the bulk. The size of the fraction can be determined by the issuer, or ‘gatekeeper’, responsible for looking after the commodity in the bulk. For example, the World Gold Council’s recent pooled gold interest (PGI) product, offers a fractionalised unit that is one thousandth of an ounce of a LBMA Good Delivery gold bar. Because the LBMA Good Delivery gold bar is roughly a 12kg large gold bar, the likelihood of physical delivery is lower because of ultimate indivisibility of the bar itself. By way of contrast, the Abaxx Spot gold product fractionalises a 1kg bar of gold, meaning that physical delivery of the undivided interest is more viable for a greater number of token holders.

These two examples, where fractionalisation has been achieved using the undivided interest structure but have not been tokenised, highlights the multiple choices that are involved in designing a fractional solution in respect of a commodity.

A number of factors influence the structuring choice, including:

As a general rule of thumb, the choice of using DLT brings the product ‘on-chain’ whereas not using DLT keeps it ‘off-chain’. This can influence the legal frameworks that apply to the fractionalised instrument. For example, the EU Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) Regulation defines ‘crypto-assets’ as assets that are a “digital representation of a value or of a right that is able to be transferred and stored electronically using distributed ledger technology or similar technology“.8 So, by choosing DLT, the fractionalised instrument immediately falls within the scope of the MiCA Regulation, or any equivalent that might exist in the relevant jurisdiction. This can then lead to forum shopping for regulatory arbitrage.

If the objective is to give an investor the ability to take physical delivery of the underlying commodity, rather than to create a cash-settled alternative, then an undivided interest approach may be preferred, since in such a scenario, the enforceability of the fractional owner’s legal title then becomes paramount. This can only be determined, with any certainty, where the laws applicable to the sale and purchase of the underlying commodity and the location of the commodity support the enforceability of the legal title of the fractional owner. For the reasons discussed above, legal certainty is harder to achieve in the on-chain public ledger context than in either the on-chain private ledger or off-chain context. The gold and silver backed tokens issued by Kinesis are an example of an on-chain public ledger that uses the undivided interest approach, but restricts the transferability of the tokens by restricting (through the forking of the Stellar layer 1) open source blockchain and not allowing the use of smart contracts in respect of the token, presumably to help ensure compliance with laws of the relevant jurisdictions.

As for whether to fractionalise on-chain via a private ledger or off-chain, that may turn on whether the laws of the relevant country apply a harsher regulatory framework for a crypto-asset than for a traditional commodity product. Some jurisdictions, like China, have issued regulatory bans on private ownership of stablecoins, including those which are asset-backed by commodities.

As highlighted above, managing the regulatory perimeter for compliance with laws relating to AML, CFT or KYC becomes harder with commodity tokens travelling on a public, open source blockchain. Pax Gold, for example, retains the right to “freeze, temporarily or permanently, user access to Paxos issued asset-backed tokens including…gold-backed stablecoins“, as well as the right of seizure or forfeiture in circumstances where it is required to do so by law, including in response to formal legal directives from regulators, judicial authorities or law enforcement agencies. Paxos requires any person wishing to redeem the Pax Gold token to open an account on its platform. This means that even though the Pax Token is freely available on-chain, for redemption purposes, it will only be available to those who can satisfy Paxos’s compliance requirements. Paxos also retains the right not to permit redemption where they have determined that Pax Gold has been used, or is being used, for illegal or sanctioned activities. A token presented for redemption in such circumstances may be forfeited.

It is clear that although there are benefits from on-chain fractionalisation solutions, the challenges arising from decentralisation mean that there may be more impediments to rights of redemption. This is because the laws associated with regulation of on-chain activity are still evolving and do not have the same maturity as the laws that apply to off-chain structures. As such, where the investor group being targeted comprise refiners, smelters, jewellers or industrial consumers, they are more likely to rely on the ability to take delivery of the commodity represented by the fractional solution and will therefore wish to reduce their risk on redemption failures. This, in turn, invites solutions that are off-chain.

There are clearly pros and cons in the choices associated with fractionalisation of commodities. The commercial or strategic choices have to be balanced against legal structural choices. As we argue in this paper, the legal structure that forms the foundation of how the fractionalisation is achieved, itself offers up a number of alternatives that influence the eventual design of the fractionalised solution. The physical nature of commodity products means that not everyone can create a credible fractionalised commodity product. Having confidence or trust in the ‘gatekeeper’ is, in our view, one of the most important factors in determining the success or failure of the fractionalised solution being offered.

Footnotes