In circumstances where our collective efforts to keep the global temperature rise to 1.5°C are unsuccessful, at a societal level we will have to adapt to the consequences that will follow. As discussed in our previous client briefing, our ability to achieve the 1.5°C target is looking more remote, and this invites us to take a hard look at the state of play in adaptation finance.

Until now, adaptation finance has mostly been discussed in the context of funding arrangements to support developing countries. The cost of adaptation for the private sector in the developed world has hardly been addressed, perhaps on the assumption that this can be readily financed using existing financial instruments. However, as we discuss below, current adaptation finance structures only work where there has been some form of public or government sponsorship or role. This limits the scale of financing and leaves the private sector at the mercy of the public sector’s priorities and budgetary capacity. The biggest risk therefore is that climate change exposure impacts private sector assets adversely to the point where the asset is either uninsurable or the required insurance premiums make the asset less marketable.

In the context of adaptation for the private sector in the developed world, the insurance sector is the ‘canary in the coal mine’. We discuss some of the challenges the insurance sector faces in supporting adaptation finance in this paper and highlight the importance of changes needed to the capital regulatory framework for insurers.

‘Adaptation’ can be defined as “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects“.1 From this definition, adaptation occurs in two systems – (i) in human systems, where it seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities; and (ii) in natural systems, where it materialises as intervention to facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects. The cost associated with the process of implementing adaptation are ‘adaptation costs’ and could be defined as “the costs of planning, preparing for, facilitating and implementing adaptation measures, including transaction costs“.2 The act of providing or raising finance to support or pay for these adaptation costs is, ‘adaptation finance’.

As the impacts of climate change become more severe, adaptation costs are rising by the year. The 2023 Global Landscape of Climate Finance indicates that developing countries will need USD 212 billion per year in adaptation finance up to 2030, and USD 239 billion per year between 2031 and 2050.3 This cost relates to developing countries only; developed countries also face the cost of adaptation but the assumption is that they do not require financial support via international treaties such as the Paris Agreement, in the manner that the developing countries do. This acknowledges the reality of the gap between the Global North and the Global South in that the Global South is less equipped to look to financial market solutions or tools to fund these costs.

The difference between the finance required to meet the adaptation costs and the finance available, is termed the ‘adaptation finance gap’. Needless to say, the wider the adaptation finance gap, the greater the adverse climate consequences and the higher the losses and damages that could follow from human or the natural systems’ ability to adapt to its surroundings.

To date, the concept of adaptation finance has mostly been focused on public sector sources of finance, with the role of the private sector almost being an afterthought. Most policy papers define adaptation finance in language neutral to whether the source of finance is private or public but largely only describe public sector financing sources.4 Furthermore, the notion of adaptation finance, at least in the context of the Paris Agreement, is entirely focused on the adaptation costs of developing countries. The reality is that in a 2 degree plus world, all countries will have adaptation needs.

Public sector adaptation finance is largely characterised by grants and loans, both concessional and non-concessional.5 In particular, debt remains the most utilised instrument under adaptation finance globally, increasing in 2021–2022 to 80% of total adaptation finance from 70% of flows in 2019–2020.6 The latest data from the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) indicate that in 2021–2022, project-level market rate debt constituted USD 37.5 billion (or 59%) of average annual adaptation flows.7 This represents an increase from 2019–2020 when project-level market rate debt accounted for USD 24.2 billion (or 46%).8 While the amount of grants has increased, international public finance flows are nevertheless dominated by loans (62 per cent, of which around a quarter are non-concessional).9

The table below provides a useful snapshot of the specific types of debt typically utilised by the public sector in adaptation finance:10

| Type of Funds | Financing sources | Instruments | Sample sub-instruments for urban settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Municipal government | Local revenue generation | Utility fees Open space funds/land value capture General obligation bonds Local property, income, and sales taxes |

| State/provincial government | Grants, incentives, technical assistance funds | Insurance Tax advantages Low-cost project debt Infrastructure investment funds Shared taxes Intergovernmental funding transfers/revenue sharing |

|

|

National government |

|||

| Public Finance | National DFIs | Grants, project debt (low-cost or market rate), technical assistance, risk instruments |

Risk mitigation support of PPP Project level debt Project preparation facilities and other technical advisory Insurance |

| Bilateral DFIs | |||

| Multilateral DFIs | |||

| Climate Funds | Grants, debt, equity, guarantees | Dedicated climate funding (i.e., Adaptation Fund) |

The variety and innovation of the financial instruments used for adaptation finance have taken us this far. Given the need to scale up adaptation finance further both in the public and private funding context, the question should be asked if more, or different, tools are needed.

Many of the instruments in the table above cannot be achieved by the private sector acting alone. This invites either (i) a public-private partnership model (for example, funding initiatives led by multilateral development institutions or sovereign wealth funds working together with the private sector), benefitting from the leverage of public and private finance or (ii) an entirely new class of purely private finance focused on adaptation.

Logically, in the near term the former will be easier to scale but in the medium term, the latter will become essential, for the reasons we outline below.

The fact that the current definitions of adaptation finance face many questions, either in being overly focused with the public sector or with other hurdles such as ever changing environmental parameters11 is the focus of a report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (the IISD Report).12 The IISD Report finds that the absence of a clearly defined taxonomy that permits a clear distinction between adaptation finance and development finance, prevents the delivery of data that might support the build out of a better definition of adaptation finance. Private capital providers – including banks, institutional investors, and private equity – currently contribute just 2 per cent of the tracked finance for climate adaptation.13 The data that would give researchers a better foundation to determine what the private sector would need to create bankable adaptative financing solutions, both for the developing world and the developed world, is quite limited.

Bridging the adaptation financing gap using private sector finance is the most direct opportunity to allow for scale and is what is being called for by the decision on the revised “new collective quantified goal 14 at COP 29 in Baku (see our previous client briefing). The biggest obstacle for private sector participation, at scale, is the traditional financier’s measure of how a return on capital for an investment is determined. Traditional revenue models do not fit well with adaptation finance because, often absent a government’s involvement, there is no revenue source to support that return on capital. Sometimes, adaptation finance is needed just to avoid a loss of asset value. Unlike the public sector, the private sector is yet to create the tools that allow for other economic benefits (in the vein of positive externalities leading to social benefits) to count towards the value proposition of engaging in adaptation finance. In the public finance context, the social benefits (i.e. a public return) of investing in adaptation and resilience are clear even if the metrics to support it are not always consistent. In short, to mobilise adaptation finance in the private sector, a paradigm shift will be needed. For the reasons we discuss below, we consider that this is now urgent, and cannot be postponed.

The Financial Times ran a series of articles during the course of 2024 on the theme of ‘The Uninsurable World’. The key message of those articles was quite simple – “Global warming is making extreme weather events such as storms, floods and wildfires more frequent and severe, and therefore increasingly difficult for the [insurance] sector to cover.”15 Examples of such extreme weather events in immediate memory include the wildfires in Los Angeles in 2025, flooding in Germany and Spain in 2024, six hurricanes hitting the Philippines in a month in 2024, flooding in the United Arab Emirates in April 2024 and heatwaves in Japan and Australia. The UN’s World Meteorological Organisation’s report on 2024 lists 152 unprecedented extreme weather events in that year.16

Munich Re estimates that “Worldwide, natural disasters caused losses of US$ 320bn in 2024 (2023, adjusted for inflation: US$ 268bn), of which around US$ 140bn (US$ 106bn) were insured. The overall losses and, even more so, the insured losses were considerably higher than the inflation-adjusted averages of the past ten and 30 years (total losses: US$ 236/181bn; insured losses: US$ 94/61bn).“17 This comes off the back of a “run of four consecutive years when overall insurance losses from natural catastrophes have topped $100bn …“18

These increased losses have therefore, impacted (re)insurance coverage and the profitability of participating in the (re)insurance markets. Part of this excessive loss is explained by more extreme flooding and more severe thunderstorms, which are considered non-peak or secondary perils by insurers (in contrast to peak peril events such as earthquakes and hurricanes) and how many insurer risk models underestimated the risk of such non-peak perils. These models are now swiftly being readjusted by insurers leading to higher insurance premiums and, in some cases, withdrawal of insurance coverage altogether.

This is why the governments are having to step in to provide coverage of some areas that are no longer insurable or affordable. For example, the UK’s Flood Re Scheme, a government funded not-for-profit reinsurance body, seeks to limit the cost of flood insurance for properties at the highest risk in the UK. Under the scheme, if an insurer calculates that the flood risk element of a policy will cost more than the premium set under Flood Re, that insurer can cede the flood risk part of the policy to Flood Re.19 The scheme is funded by a levy charged by the UK government from the insurance industry and in 2023 covered 260,000 homes (an increase of 110,000 since 2018). The increase of homes covered by the scheme highlights the point that more homes are becoming uninsurable absent such schemes. Many such government schemes have limits for damage and cover that means, even with the benefit of such insurance, the gap between the actual loss and the insured loss, is likely to increase.

On the basis that the Paris Agreement outcomes seem likely to be more consistent with a 2+ degree scenario, these extreme weather events will only increase. The logical consequence is that more businesses and their physical assets will be exposed to the risk of increasingly unaffordable insurance premiums and, in some circumstances, an absence of insurance coverage. Uninsurable assets very quickly suffer from loss in value because of the owner’s increased exposure to having to bear a loss from an event affecting the asset. Disposing of or raising finance against such assets similarly becomes more challenging.

If private sector adaptation is to be scaled, the economic rationale for financing adaptation can be linked to metrics that are more familiar to the insurance industry than they are to the banking industry.

There are many lessons from the insurance industry that can be applied to or adapted for the adaptation finance sector. For example, insurance industry leaders like Marsh have developed quantitative and qualitative analytical tools that assess both asset-level considerations (e.g. risk to physical assets) and system-level considerations (e.g. critical infrastructure and supply chains) in assisting businesses to determine their adaptation and resilience to climate change.

Marsh recognises that adaptation by a business leads to a greater chance of avoiding economic losses and can increase revenue and cost savings. Similarly, if adapting to structural changes is considered an essential part of strategic business management (including taking into account social, political and environmental factors/ changes) to minimise risks and potential costs for the business, then the physical impacts of climate change is one such structural change which should be taken into account by businesses.20

Marsh’s ‘Climate Adaptation Framework’ includes tools that, in assessing the adaptation opportunities for a business’s physical assets, allow it to assess the costs and benefits of each adaptation measure that could be implemented by a business whose physical assets are exposed to climate risk. Using catastrophe models, insurers can quantify the impact of resilience measures implemented by such a business, for example by altering the elements of the model that consider ‘vulnerability’.21 This enables the adaptive benefits to be measured in terms of reduced risk which, in turn, potentially leads to a saving in the insurance premium. In simple terms, a business can invest in adaptation steps that can reduce its exposure to increased insurance premiums. However, random adaptation steps will not necessarily work as the adaptive steps must be recognised by the insurer who, in turn, is constrained by its own regulatory requirements.

Businesses should therefore work closely with their insurers to help determine their climate risk and identify solutions that would be recognised by their insurers. However, the question of how those solutions should be funded by a business, is the biggest challenge for the private sector today.

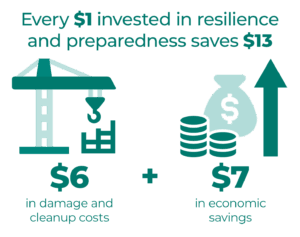

In public sector adaptation terms, the costed benefits of adaptation have been studied. According to a report co-authored by the US Chamber of Commerce22: “Each $1 invested in disaster preparation saves $13 in economic costs, damages, and cleanup.”

However, almost all of the examples in the study involve measurement tools that are easier to apply in the public sector than the private sector. Most private sector entities are forced to seek to fund their adaptative measures using their own balance sheet or borrowing using traditional lending terms. Capital market tools, such as green bonds, will allow use of proceeds for adaptation work but the repayment of the bond has to flow from the traditional business of the organisation. A mere reduction in risk of loss or maintaining the insurability of the asset itself cannot today repay the bond investor or the traditional lender.

The willingness of insurance companies to deliver insurance products that support adaptation actions can currently be addressed somewhat by how the asset is valued in that insurer’s risk assessment process. However, most insurance products which protect assets subject to climate risks are annual products and, therefore, do not assess longer term risks of climate related risk exposure and their ability to develop products with a longer-term risk horizon in mind is constrained by the Solvency II regulatory regime that applies to EU insurers.23

Solvency II, a risk-based capital regime, requires insurers to hold an amount of capital which is calculated based on the risks they take on and specifies clear methodologies for calculation of those risks. The calculation of insurance liabilities under Solvency II, involves insurers determining a ‘best estimate’ of their liabilities and a risk margin. The amount of capital which needs to be held is by default calculated using a standard model, although insurers can use a bespoke internal model or a mixture of both.

The standard model includes a module for natural catastrophe risks. The European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) has identified that “current capital requirements have been calibrated based on the available historical data for past events. Sustainability developments and, in particular, climate change risks, are expected to materialise over the next 10 to 20 years. Climate change is likely to increase the frequency/severity of natural catastrophes. Such expected fluctuations need to be captured in the risk management strategies in a forward-looking manner in the ORSA24. Past data on its own is unlikely to be a good predictor of future risks.”25 Of course, insurers also need to price products in a prudent manner, and ensure that they have sufficient capital to pay claims – an insurance product which provided a platform for adaptation would be no use if it failed in its primary purpose of meeting the liabilities it was purchased to cover.

Solvency II is designed to reflect the exposure of insurers to risks over a one-year time horizon and, as EIOPA acknowledges, “the medium to long term impacts of climate change cannot fully be captured in Solvency II capital requirements“26. Notwithstanding this, EIOPA does not suggest a change to the one-year time horizon for assessment of risk but instead, suggests that other complementary tools such as scenario analysis and stress testing be used as means to capture the impacts of climate change, including adaptation risk.

Even if an internal model is used to calculate the capital which an insurer is required to hold, there are constraints in using internal models for measuring risks over longer time frames because there is lack of suitable data for calibration of existing risk models to allow for measurement of risk such periods.

If, as now seems inevitable, adaptation is set to become a critical element of the world’s response to climate change, in the Global North as well as in the Global South, there is an urgent need for a greater focus on adaptation finance in the private sector. The insurance industry will have a critical role to play in this.

In order to scale the insurance industry’s investment in adaptation solutions, two key obstacles will need to be overcome. The first is access and availability to suitable data on forward looking risk. The second is the need to adapt current models “in the absence of known market prices and historical data, taking into account trends that are implied by climate change.”27 Until these are overcome, or the Solvency II regime is amended to be less dependent on historical data in the context of climate change risks, there will remain constraints on the insurance industry to create suitable tools to support the markets adaptation needs.

Footnote