Welcome to Minegolia

In this briefing, we take a look at the development of the mining sector in Mongolia

Introduction

Mongolia, the landlocked country between China and Russia, currently rests on the brink of economic transformation, as it celebrates the mining sector’s 90th birthday this year. Its untapped mineral wealth, coupled with its rapidly developing mining industry, have created the world’s biggest resource boom. As with any boom, there are concerns about stability and sustainability. In such an environment, investors need to be armed with the hard facts, insight and pivotal developments – the focus of this article, capable of influencing the decision to partake in Mongolia’s intriguing story.

And the story is indeed intriguing. Whilst current GDP growth is, by any standards, outstanding some commentators have suggested that there is still additional growth which is, as yet, unexploited – as Mongolia literally sits on mountains of minerals.

Since 1990, following the introduction of democratic elections, Mongolia has worked at establishing an equilibrium between the interests of the State and that of the private sector to tap into the additional growth. It is hoped that with recent legal reforms, aimed at promoting transparency and consistency, with particular success in the mining sector, the country will fully embrace this principle. However, as with any developing economy, investors should continue to watch the country’s progress.

Mining legislation – a step into a free market economy

Initially based on the writings of Chinggis Khaan, the relatively new laws of Mongolia are now based on principles of democracy and privatisation and have emerged following the collapse of communism over 20 years ago – the aim was to create a free market economy.

The 1997 Minerals Law was a positive step in that direction, under which taxation and royalty burdens were low, making Mongolia a favourable place for investors. This law was superseded in 2006 with a new Minerals Law1 (the New Minerals Law). The New Minerals Law attempted to try and find a balance between expansion and foreign led developments as against national interests over Mongolia’s geological riches.

Licence to…drill?

One way in which the New Minerals Law safeguards Mongolia’s mineral wealth is through licensing. This captures all minerals in Mongolia, with the exception of petroleum, water and natural gas. Both exploration and mining licences can be granted to only Mongolian legal entities, although it is sufficient for foreign investors to set up wholly-owned subsidiaries in Mongolia.

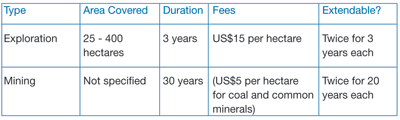

Exploration licences are granted on a first-come-first-served basis for a period of three years. They are extendable for two further periods of three years each, for areas of land between 25 and 400,000 hectares. Licence fees are applicable and holders are required to have a minimum spend on exploration work.

Mining licences are granted for a period of 30 years, extendable twice for 20 years each time. In addition, annual licence fees apply and mineral royalties are payable on the sale of coal (and common minerals (Common minerals are those as prescribed by the Government)) and other minerals (e.g. gold, copper, zinc) at 2.5% and 5% respectively. These are standard flat rate royalties.

Use it, don’t abuse it or lose it

There is a set process for applications for exploration and mining licences. Applications are made on a special government agency approved form together with supporting documents, detailed in the New Minerals Law. Once submitted, the application is registered and processed, with the decision being provided within a couple of weeks. Currently, there is no clear guidance on what grounds licences can be refused.

Moreover, the process of renewing licences offers no assurances, thus forcing investors to continually re-evaluate the mineral potential of their tenements. A recent trend appears to be revocation of licences. In late 2010, hundreds of licences were revoked under the 2009 Law on Prohibition of Mineral Exploration in Water Basins and Forest Areas (the Water and Forest Law) – aimed at protecting Mongolia’s environment. There have been other sporadic revocations. For example, the recent sale by Ivanhoe Mines of a 57.6% interest in SouthGobi Resources Ltd to the Aluminium Corporation of China (Chalco), triggered the Government to suspend operations and revoke exploration and mining licences of SouthGobi Resources Ltd. The Government’s need to review the new structure comes as a surprise, however many believe that underlying factors such as the perceived reliance on the Chinese market (or reduced government take on account of onward sales) has played a significant role – and some may say, justifiably so. In sum, like many resource-rich areas, the Government has adopted an approach of ‘use it, don’t abuse it or lose it’.

Concerns over licences?

Many commentators have expressed concerns over the outright ban on the issuance of new exploration licences, which began in 2010 – a ban that has now been extended until the end of 2012. However, there may be legitimate reasons for the ban since the newly anticipated law in this area, will aim to address public concerns over environmental degradation as well as regulate and curb certain undesirable activities such as:

- Trading ‘licences as commodities’.

- Illegal mining.

Recent weeks have also witnessed a moratorium on the issue of new special mining licenses for a period of five years with the aim of protecting the environment.

Gaining access to the upside – Mongolia’s early missteps

An instrument, which may have discouraged certain investors from participating in Mongolian mining projects and yet was geared at protecting Mongolia’s mineral wealth and maximising revenue, was the Windfall Tax. It imposed a 68% tax on the sale of metal. This was applied on copper (above $2,600/ton) and gold (above $500/ounce). After much criticism, this tax was repealed and replaced by a new Surtax Royalty Scheme, incorporated into the New Minerals Law.

The rates of the Surtax Royalty vary from 1% to 30% and depend on the market price, the type of mineral and the scale of processing of the minerals. All are applied in addition to the standard flat rate royalty, namely 2.5% on coal (and common minerals) and 5% on other minerals including but not limited to zinc, copper and gold. It is unclear at which stage of the process the Surtax Royalty rates will be imposed, how the market price will be determined or how the tax will be collected. For obvious reasons, this development remains a positive step but only time will tell how it works in practice.

Getting a fair share

It comes as no surprise that with growing revenues and a developing economic environment the Government has been keen to carve out what it would consider a ‘fair share’. The resulting approach, has been the introduction of revised state equity participation rights. These rights, which were introduced under the New Minerals Law, allows the Government a right to a 34% equity stake in projects, where it provided no funding and a 50% stake in projects involving state funding. The affected projects are those involving minerals of ‘strategic importance’. This was defined, for the first time by reference to national security, in addition to other factors including economic and social development, as well as, production levels. The existence of a strategic deposits list brings certainty and ensures the Government is not getting more than a ‘fair share’.

And yet a dialogue

In light of this changing regulatory market, the Government has been and is willing to enter into a dialogue in relation to the form and amount of state participation. One instrument facilitating this dialogue has been the Investment Agreement (IA), which is available to mining licence holders undertaking an investment of more than US$50 million during the first five years of a project. The IA will set out agreed tax rates, mineral royalties and financing arrangements, all of which are dependent upon the duration of the project and the investment size. More importantly, a well negotiated IA can override legislative provisions, bring stability to investors already exposed to considerable physical and project risks and provide a tailored approach key to sector development. This should put the Government in good stead to enter into IAs in the future.

Still, it is important to remember that any agreement with a sovereign state will not eradicate the fight for control parties may have internally, against which investors should also protect themselves at all costs.

Putting up fences or bringing stability?

In its quest to find a balance between the rights of all stakeholders, has the Government gone too far with the introduction of its most recent law? The Law on the Regulation of Foreign Investment in Business Entities Operating in Sectors of Strategic Importance (the Strategic Foreign Investment Law) was passed by Parliament in the last couple of weeks, with the purchase by Chalco acting as the catalyst. The Strategic Foreign Investment Law introduces a scheme of approvals necessary for acquisitions in relation to state-owned and private investments, with the former being more onerous.

The most notable provision requires investors for any acquisition to obtain approvals from the Government and subsequently Parliament, to acquire a stake of more than 49% in businesses in ‘strategic sectors’ where the transaction is worth in excess of US$76 million (100 billion tögrög). These ‘strategic sectors’ include: minerals, banking and finance, media and telecommunication, according to the draft read to Parliament.

With investors breathing a sigh of relief at the latest version of the law, which has a narrower scope than initially anticipated, commentators have suggested that the Strategic Foreign Investment Law is in fact a positive development for Mongolia by bringing it closer to the developed mineral-wealthy economies by injecting stability and clarity.

Raising capital…raising Mongolia’s presence

To become a mining powerhouse and compete with the more mature resource-rich economies, Mongolia must take one more step – this time in the sphere of capital markets. Until recently, this was not quite possible; despite the establishment of the Mongolian Stock Exchange (MSE) in 1991 and the enactment of the Securities and Exchange and Corporate Laws in 1994 and 1995 respectively (the Securities Laws), the MSE has been slow to develop and today remains one of the world’s smallest bourses.

The recent set up of a partnership with the London Stock Exchange (LSE), aimed at utilising LSE’s experience to modernise the MSE. Spurred by specific trading requirements on mining licence holders for minerals of ‘strategic importance’ (10% of shares to be traded on the Mongolian Stock Exchange), the Parliament is keen to push through the New Securities Markets Law, hoping to gain a bigger proportion of the benefits stemming from Mongolia’s rapid development.

Under the proposed law, companies issuing securities in Mongolia no longer have to be registered in the country, thus removing the burden of dual compliance of laws in Mongolia and the jurisdiction of incorporation. Moreover, the law allows companies with securities in other jurisdictions to list and trade securities on the MSE.

Depository receipts – financial instruments issued by custodians or institutions holding securities which carry rights in the underlying securities – are also a prominent feature of the proposed law. Under the New Securities Markets Law, the issuance of these financial instruments is permitted, where underlying assets are traded in foreign markets, simplifying secondary listings on the MSE. To enable this to work, the new law also addresses the distinction between the legal and beneficial interests, which will assist with the practicalities of setting up trustee and broker services for those holding beneficial interests.

It is hoped that these laws will attract investors encouraging listing and capital raising on the MSE and lifting Mongolia’s capital markets presence, which may be accomplished in part by the highly anticipated public listing of Tavan Tolgoi in London, Ulan Bator and Hong Kong later this year.

Conclusions

It is well recognised that a stable legal infrastructure will be key in promoting Mongolia’s mining sector. Mongolia’s laws have undergone major transition in recent years and arguably this has incentivised investors to engage in the country’s most prominent business sector. In fact, it was the mining sector which increased the country’s GDP by a significant 28% in 2011. However, Mongolia’s legal framework is still a work in progress. It is hoped that the proposed and newly implemented laws will strive to put Mongolia on equal footing with other mineral-rich markets, and the current review of the New Minerals Law, which it is anticipated we will hear about sometime following the June 2012 elections, will endeavour to find a balance between the interests of the Government and investors, whilst simultaneously protecting Mongolia’s unique environment and benefitting the ordinary people.

Investors should not be deterred in making advances into Mongolia, but instead do their homework and be prepared to balance the risks against the unparalleled benefits, which may ensue if they partake in this unique opportunity to unlock the vast natural resources of one of the planet’s fastest growing economies.