India’s spring board

This article first appeared in the April 2014 issue of Port Strategy and is reproduced with permission. www.portstrategy.com

There are positive signs of progress in the development of India’s port sector as some big ticket deals are expected to take place in 2014.

According to the press, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd (APSEZ) agreed in early 2013 to buy Dhamra Port Company Limited, a joint venture between Larsen & Toubro Limited and Tata Steel Limited, in Odisha, provided that the current operator gets environmental and coastal zone approvals.

Paradip Port Trust is also planning to develop containerised cargo handling infrastructure at Paradip Port to cater for growing box cargo exports, a project in which Container Corporation of India and Warehousing Corporation of India have shown interest. This is welcome news for players in India’s port sector, which has seen mergers & acquisitions deal volumes decline since 2011 due to sluggish economic trends, a slowdown in economic reforms, rising interest rates, high inflation and a depreciating Indian Rupee.

Ports play an important role in India’s overall economic development. At present, 95% by volume and 70% by value of international trade in India is carried on through maritime transport. There are currently 12 major ports and 187 non-major ports in India. Major ports fall under the control of Ministry of Shipping and non-major ports are operated under concession from State Maritime Boards (SMB).

As one of Asia’s growth engines, and a lower cost manufacturing and outsourcing hub for advanced economies, India’s port sector has witnessed significant growth over the past decade with total traffic handled increasing from nearly 380m tonnes in FY01-02, to approximately 934m tonnes in FY12-13. This increase in demand in maritime transport has exerted pressure on India to expand and improve its port facilities.

The Indian Government has recognised the importance of privatisation to increase capacity and to improve the performance standards in the ports sector. In January 2011, the Ministry of Shipping introduced its policies for the maritime sector of India for the next 10 years. The ‘Maritime Agenda 2010-2020’ replaced the previous National Maritime Development Plan, which was launched in 2005 and was to end in March 2012. Both documents focus on the development of port infrastructure with significant involvement from the private sector.

Broad base

There are now a total of 72 PPP projects in India’s port sector in different stages of implementation, 30 of which are under operation. The well known ones include the Nhava Sheva International Container Terminal at JN Port (completed in 1999), the third container terminal at JN Port (completed in 2006) and the second container terminal at Chennai Port (completed in 2009).

These PPP projects are dominated by major global port operators, including APM Terminals (Mumbai and Pipavav), DP World (Chennai, Mundra, Nhava Sheva, Visakhapatnam, Cocohin) and PSA Singapore (Tuticorin, Chennai and Kolkata).

But despite the importance of PPP projects for India’s port sector, progress has been protracted.

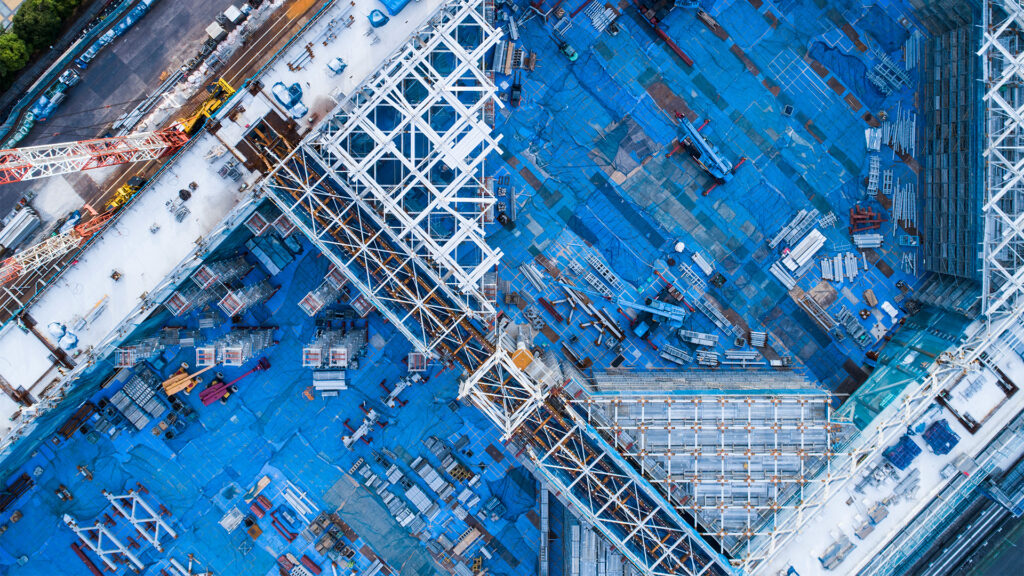

At the bidding stage, the process has been slow due to bureaucratic procedures at most major ports. At the post award stage, projects have been delayed due to the time taken to obtain environmental and other government approvals. It is estimated that around five years is needed to obtain all governmental approvals. It then takes another three to four years for construction of the port.

India’s new Land Acquisition Act arguably will add further delay to PPP projects. This new legislation was passed by Parliament in September 2013 and came into force on January 1, 2014. Under this landowner-favoured legislation, PPP project proponents will be required to obtain consent from 70% of the landowners for acquiring land for a greenfield port project.

Inadequate infrastructure has also contributed to low performance standards at Indian ports. The design of the current port infrastructure is out of date and a large number of ports are not equipped with dedicated and efficient cargo-handling facilities. The future generation of mega vessels require a draft of 13m to 15.5m, whereas several Indian ports cannot handle vessels that have a draft requirement of more than 12.5m. Additionally, the roads within most ports are narrow and the connectivity between hinterland and road, which accounts 60% of cargo traffic in India, is poor.

Despite some continuing challenges, there are positive signs in India’s ports sector and the potential for growth and development is enormous. However, India’s port sector is currently facing structural problems which require innovative solutions from all stakeholders involved in the sector.

Policy reforms to improve connectivity between ports and other modes of transport, including increasing rail shares, expediting government approval processes and upgrading infrastructure, are key to addressing the capacity constraints facing the industry.

For more information, please contact Connie Chen, Special Counsel, on +61 (0)2 9320 4616 or connie.chen@hfw.com or Alistair Mackie, Partner, on +44 (0)20 7264 8212 or alistair.mackie@hfw.com, or your usual contact at HFW.