COVID-19 and commodity trade finance: The way forward

We look at the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic across commodity markets globally and how this is impacting financing arrangements including ‘MAC’ clauses, financial covenants, ‘corona clauses’, events of default and force majeure as well as recent guidance from the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) on electronic trade documentation and flexibilities under the ICC rules.

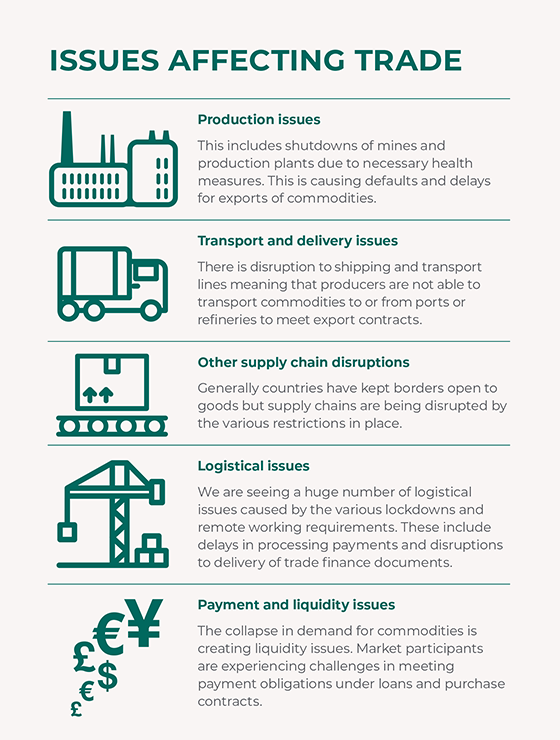

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a significant impact on international trade. The World Trade Organization has estimated world trade will fall by up to 32% in 2020 as the pandemic disrupts the economy. 1 Most commodity markets are experiencing dramatic falls in prices as demand and consumption have fallen and countries have been forced to put in place restrictive measures to contain the pandemic. These measures are affecting how goods and commodities are able to flow across the globe. The issues affecting trade are diverse, vary between countries and are evolving rapidly, however, these issues can generally be grouped into the categories shown below.

How do these issues impact on commodity trade finance?

Trade finance covers a broad range of financing arrangements for the production, export and sale of commodities. In structured trade finance, this includes pre-export finance (PXF) facilities, prepayment arrangements, borrowing base facilities and other structures, all of which aim to provide finance for the production of goods. The issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will be different for each of these structures and will be dependent on the specific drafting and deal terms. However, the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to raise some common issues for borrowers across most types of trade finance facility. A number of these issues are also relevant for corporate loans generally.

Liquidity issues

It may seem paradoxical in an environment where the Federal Reserve and ECB have injected significant liquidity into the economy, however, one of the big issues facing market participants is the tightening of supply of trade finance. Trade finance products have traditionally had low default rates in part because transactions are structured so that when the underlying goods are sold, the proceeds are applied to repay the loan. Despite this, the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on credit markets is that many banks are reducing their risk exposure. This means that new trade finance lending will likely be impacted over the coming months. It will become harder for certain commodity players to arrange new money deals and new client on-boarding is likely to be more challenging. Loan pricing will be impacted for certain names. On the other hand, the current environment is creating opportunities for trading houses who identify opportunities and solutions amid market dislocation and price volatility. The volatility is itself creating a liquidity risk for certain players who are unable to meet margin calls under commodity hedging contracts. We are yet to see the full impact.

We are starting to see the tightening of liquidity have an impact on existing trade finance, with many borrowers looking to draw on existing credit facilities to ensure sufficient cash reserves. There are several issues for borrowers to be aware of when thinking about drawing on existing facilities, whether committed or uncommitted funding.

Financing in the commodities sector is often provided on an uncommitted basis. This means that the lender has no obligation to provide funds and where structured as an overdraft, the bank can demand repayments at any time. These facilities are often used for working capital and are intended to be flexible, for example, enabling a borrower to purchase spot commodities at short notice to take advantage of arbitrage and other opportunities. In the current environment, borrowers need to plan for liquidity to be tightened and for any uncommitted facilities that they might have to become unavailable.

How are committed funds likely to be impacted?

For committed funding, borrowers need to be aware of the drawstop events under their existing facilities. These are events that give the lender the right to refuse further drawdowns. If the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic trigger a drawstop event, this may leave a borrower at risk of losing access to a crucial revolving credit facility or working capital line. If a drawstop event has occurred, or looks likely, then urgent discussion will be advisable with the lender in order to agree terms of a waiver or amendment.

One of the key conditions precedent that a borrower must meet for a drawdown is that there is no default under the existing facility. The definition of ‘default’ will vary but it will generally include potential as well as actual events of default. In the case of a rollover loan, the conditions for rolling over funds are generally less onerous and a borrower will typically be able to rollover a loan even if a potential event of default is outstanding (but not an actual event of default).

Another condition precedent to a drawdown will generally be that all repeating representations are true in all material respects. Repeating representations will generally include representations that:

- there has been no material adverse change in the assets, business or financial condition of the borrower/obligors since its most recent financial statements; and

- there is no default which has, or is reasonably likely to have, a Material Adverse Effect.

The meaning of ‘Material Adverse Change’ and ‘Material Adverse Effect’ are discussed in further detail below. The key point is that if there is a severe impact on a borrower’s business from issues relating to COVID-19 it might make it more difficult to give these representations. This will make it more difficult to draw down under an existing facility.

Producers of commodities might also have existing borrowing base facilities. These are loan facilities where the amount that can be borrowed will depend on the value of a pool of assets or ‘borrowing base’. As the mark-to-market value of the borrowing base changes, the amount that can be borrowed will adjust. Because the value of most commodities has fallen significantly since the start of the pandemic, this might create shortfalls in the borrowing base. Borrowers might then have to prepay the facilities to avoid defaults; this in turn might create short-term liquidity issues.

|

WHAT ARE THE KEY TERMS OF LOAN FACILITIES THAT BORROWERS SHOULD CONSIDER? For existing loans in the commodity sector, the disruptions to supply chains, payment mechanisms and production are making it harder for some borrowers to comply with the terms of their historic loan facilities. Borrowers will need to be aware of the key terms of their funding arrangements so they can start engaging with lenders early if waivers or restructuring are needed. Representations As mentioned above, key representations will likely need to remain true to avoid a drawstop to further drawdowns. Certain representations will also be repeated at other times, including on the first day of each interest period. As an example, a PXF facility will usually include representations about any export contracts. The borrower will need to confirm that there are no material breaches under any export contract. If there are payment or delivery issues resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, it might be difficult to give these representations. Financial covenants and cover ratios Loan agreements will often contain financial covenants which allow a lender to monitor financial performance of the borrower. Financial covenants are often tested on a quarterly basis with reporting 30 days after the quarter end. Borrowers will therefore need to check their financial covenants closely. It might be possible to ‘add back’ certain losses resulting from the impact of COVID-19 to EBITDA, if they can show that these amounts are exceptional items. This will need to be carefully looked at depending on the drafting of the particular covenant. New loans are already starting to include so-called ‘corona clauses’ which give borrowers more flexibility to allow them to ‘add back’ amounts for coronavirus related losses. If a breach of a covenant is likely then a borrower should start discussions with their lenders as soon as possible to discuss the options, including looking at waivers and prepayments. PXF and prepayment facilities are also likely to contain cover ratios. These monitor whether commodities to be sold under an export contract will generate enough cash to make loan payments. With prices falling across a number of commodities, we are seeing cover ratios put under strain for a number of borrowers. This means borrowers will need to think about how to ‘cure’ any breaches by prepaying or topping up the volume of exports (if there is sufficient production capacity). Other covenants As well as the usual covenants in corporate loan documents, trade finance facilities will often contain bespoke covenants which are specific to the commodity contract. For example, a PXF facility will likely include a covenant that the borrower/exporter complies with the terms of the export contract. This will likely include an obligation to make all export deliveries on time. If the borrower has production or transport issues resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic then it might be difficult to meet these contractual obligations. This in turn might create a risk of a breach of undertaking under the financing. Events of default Events of default are often heavily negotiated and borrowers will need to look closely at the exact terms in their facilities to fully assess the impact of the issues arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. A few of the key events of default that are likely to be relevant are as follows:

|

Is force majeure relevant?

Generally, loan agreements that are governed by English law will not contain force majeure clauses. English law will also not imply a force majeure clause into a contract that otherwise does not include one. This means that a borrower will not generally be able to assert force majeure if it finds itself unable to perform under a loan due to the impact of COVID-19.

The closest concept to force majeure in a typical loan agreement will be the grace period for non-payment. This clause generally allows a short grace period for a borrower if they find themselves unable to make a payment because of an event outside of their control. This is generally limited to events that impact the treasury function of a business. This might be relevant in the current environment, however, the grace period is usually very short, typically

2 to 5 days.

Force majeure may be relevant under a related trade agreement that a borrower has entered into. For example, many Chinese importers have already declared force majeure in relation to a wide range of commodity trade contracts. The particular wording of any force majeure clause and the specific circumstances will need to be carefully considered in relation to any assertion of force majeure. For further information please see the briefings published by HFW on this area. 4

What about other trade finance instruments?

What about issues in relation to more vanilla trade finance instruments, such as letters of credit, bonds and guarantees? These are instruments that are generally used to make sure payment or performance happens in international trade. Can the issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic be considered a force majeure event under these types of trade finance documents?

An underlying sale contract will need to be looked at separately from the trade finance instrument itself. For letters of credit and demand guarantees that are governed by English law, the ‘autonomy principle’ will apply. This means that a letter of credit is a standalone contract; it is a separate agreement to the underlying sale contract and even if there are performance issues under the sale contract this is not relevant for the letter of credit. The bank will deal only with the documents that are presented and not with the goods or the underlying sale. In short, the question of whether there is a force majeure event under the sale contract is separate to any force majeure event under the terms of the trade finance instrument.

Almost all international trade transactions involving documentary credits are carried out on the basis of the ICC Uniform Customs & Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP 600) and as such, must be examined through the prism of the chosen governing law.

Under Article 36 of the UCP 600, a force majeure event is an event “such as those arising out of the interruption of a bank’s business by Acts of God, riots, civil commotions, insurrections, wars, acts of terrorism, or by any strikes or lockouts or any other causes beyond its control”. This offers banks some protection from events that are outside of their control. Article 36 further provides that when business resumes, a bank would not need to honour a credit that has expired during the interruption of its business. However, force majeure under a letter of credit is still a high bar to meet and it is not clear whether banks will seek to test this protection in light of disruptions to their operations caused by COVID-19. Rejection by an issuing bank on this basis would certainly have severe reputational consequence in the interbank market for the institution concerned.

The ICC’s other model rules in relation to trade finance instruments all contain concepts of force majeure. If the relevant instrument incorporates the ICC rules, force majeure may therefore be relevant. Parties will need to look at the terms of the instrument and the ICC rules to understand whether the specific issues they are facing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic may constitute a force majeure event under the documents.

Are there any flexibilities under the ICC rules?

The UCP 600 rules entered into force in 2007, before the global financial crisis and COVID-19. In April 2020, in response to exceptional difficulties faced by market participants, the ICC issued new guidance on flexibilities under the ICC rules for trade finance documents. 5 This guidance recognises that some banks are facing difficulties processing trade finance transactions due to the current public health measures required to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidance reminds market participants that the ICC rules can be modified by agreement. For example, the five banking day examination period imposed by UCP 600, Article 14(b) may be extended provided that the parties agree.

What about electronic trade documentation?

The ICC has also recognised that most trade finance instruments still require paper documentation to process payments. The back-office staffing to process transactions is significant for banks and the disruptions caused by COVID-19 are causing processing delays. The ICC has urged governments to take emergency measures to allow electronic trade documentation. 6 We are yet to see how this will impact the market but any reform towards digitisation of trade finance will be an unintended and positive legacy of COVID-19.

|

NEXT STEPS FOR BORROWERS? Borrowers will generally need to be pro-active in thinking about their trade financing needs in light of the continued disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to their business and to global trade. As a starting point borrowers should consider taking the following steps:

|

For more information please contact:

Jason Marett

Senior Associate, Geneva

M +41 (0)79 103 3492

E jason.marett@hfw.com

Olivier Bazin

Partner, Geneva

M +41 (0)79 582 6648

E olivier.bazin@hfw.com

Footnotes

- https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm

- BNP Paribas SA v Yukos Oil Co [2005] EWHC 1321 (Ch)

- Grupo Hotelero Urvasco v Carey Value Added SL and Another [2013] EWHC (Comm) 1039

- https://www.hfw.com/insights/Coronavirus-Can-it-be-a-Force-Majeure-event-Feb-2020/

https://www.hfw.com/insights/The-COVID-19-Pandemic-and-the-Contractual-Force-Majeure-Landscape/

https://www.hfw.com/Force-Majeure%E2%80%93Now-What-A-Three-Step-Framework-for-Mitigation-May-2020 - https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/04/2020-10-the-impact-of-covid-19.pdf

- https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/04/icc-memo-on-essential-steps-to-safeguard-trade-finance-operations.pdf

- https://www.hfw.com/insights/Improving-liquidity-by-selling-debts-a-look-at-anti-assignment-provisions-in-receivables-financing/