Constructing successful partnerships – Swiss Law and joint ventures

Many projects are currently built by joint ventures or consortia, and it is not uncommon for the relationship between their members to be governed by Swiss law. This article gives a high-level overview on some points to consider in that situation. By understanding these aspects, stakeholders can navigate construction collaborations effectively and mitigate potential challenges.

Joint Ventures in Construction Projects

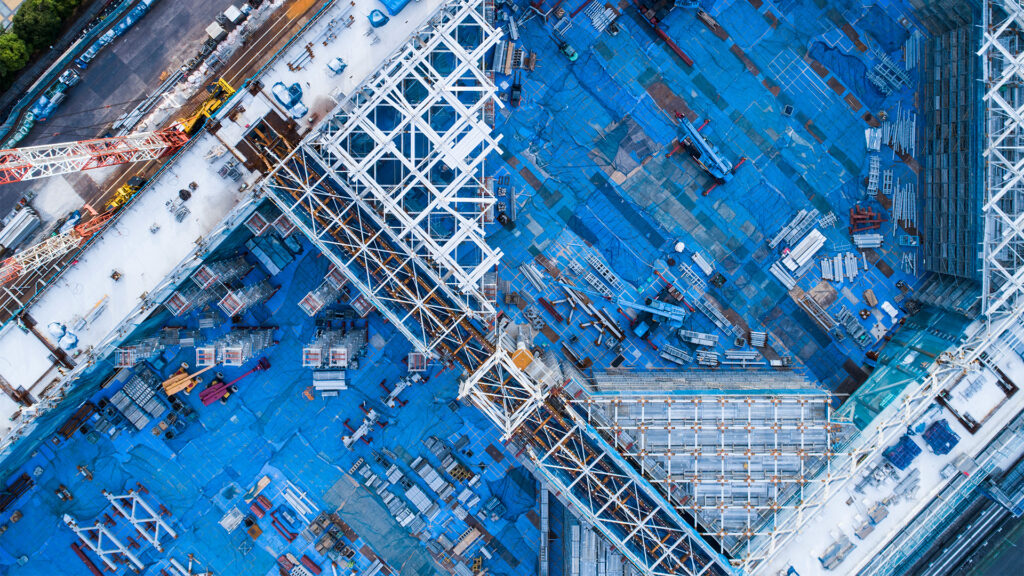

Construction and infrastructure projects are continuing to grow in scale and complexity. This trend extends not only to larger projects overall but also to their procurement strategies. Increasingly, complex work packages are being awarded under consolidated contracts — such as engineering-procurement- construction (EPC) or design-build agreements. This is being driven variously by employers, owners, sponsors and funders. As a result, contractors face the challenge of assembling diverse expertise and organisations that are able to take on the risks.

To meet these demands and succeed in competitive tender processes, contractors often form joint ventures (or consortia)1. These joint ventures bring together two or more distinct entities, each contributing specialised skills. By pooling their complementary expertise, multiple contractors can combine to tackle the different, complex and often proprietary elements of the work scope; and, at the same time, share (and reduce) – at least in principle – the potential risks involved had it been tendered by a single entity.

- Joint Ventures in Construction: Joint ventures are not novel concepts in the international construction industry. In fact, it has become standard practice for construction contracts to make specific provision for them. While some joint ventures take the form of separate legal entities, it is more common for them to be unincorporated (and simply described as such in the bid documents). From a legal perspective in terms of the construction contract, all joint venture members — at least with regard to the owner or employer client — are jointly and severally liable for the contractor’s obligations.

- Unincorporated Joint Ventures: In unincorporated joint ventures, the joint venture agreement serves as the sole contractual link between the joint venture parties. Given the ever-increasing scale of work packages, careful consideration must be given to the terms of the joint venture agreement: it governs financial, legal and practical arrangements between the joint venture members surrounding the performance of the underlying construction contract.

- Choosing Governing Law: The Swiss Advantage: When negotiating joint venture agreements, a critical consideration is the choice of governing law. Swiss law is a popular choice, even when none of the parties have direct ties to Switzerland. Why? Swiss law has long been regarded as a neutral, business-friendly and clear law for international contracts. The ICC’s 2023 Dispute Resolution Statistics2 mention once again that Swiss law was the second-most commonly selected choice of law to govern the contracts out of which the disputes which are submitted to the ICC arose. Accessibility to non-Swiss lawyers is another advantage, as Swiss Acts are officially published in German, French, and Italian, with unofficial translations available in English.

Joint Venture Agreements under Swiss Law

Three important aspects of construction joint venture agreements from a Swiss law perspective:

- Profit and Risk Allocation within the contractor joint venture.

- Decision-Making Processes within the contractor joint venture.

- Dispute Resolution Mechanisms specific to contractor joint ventures.

a) The allocation of profit and risk within the contractor joint venture

Under the Swiss Code of Obligations, each member of the joint venture will by default have an equal share of the nature and amount of his contribution. This provision is, however, not mandatory, and parties are free to allocate profits and losses within the joint venture agreement differently. For instance, in order to attract a member who brings important specific expertise to the joint venture, though whose scope is a smaller part of the overall work package, it is possible to cap the possible loss for the member but allowing it to participate equally in profit-sharing and management. There are limits however as to how the profit and loss can be allocated. For example, a clause allocating all the profits to one member and/or all the loss to another would not be enforceable (with the exception that it is possible to agree that a member whose contribution to the common purpose consists of labour will participate in the profits but not in the losses).

It is also worth emphasising that such an internal allocation does not affect the relationship between the members of the joint venture and third parties. Where the members are jointly and severally liable for obligations to third parties, the effect of the joint venture agreement would be to regulate the position as between the members and not with regard to the third party (e.g. the owner or employer).

b) Decision-making within the contractor joint venture

Often, under Swiss law, a joint venture will be considered a simple partnership within the meaning of the Swiss Code of Obligations as the contractors agree to combine their efforts and/or resources in order to complete the project or reach an objective. Swiss law on simple partnerships does not contain many provisions, and most of them are not of a mandatory nature, therefore the parties have a lot of freedom to adapt their joint venture agreement to their needs.

In the absence of express provisions otherwise, the decisions within a joint venture must in principle be made by the consent of all the members.

If not specifically dealt with in the joint venture agreement, this can be quite problematic. For example, it can delay actions being taken when they are urgent, which might for example occur if something has to be done within a certain time period or before a deadline or time bar lapses. A mechanism requiring mutual consent of all members can also be prone to gridlock or even be abused, especially in the context where the interests of most of the members are not aligned with those of the minority. Extreme cases can arise if one member wishes to replace another member in the joint venture, for instance because the composition of the members of the joint venture needs to be adapted to meet new requirements of the bidding process or because one of the members no longer meets certain criteria required to participate in a bid.

It is therefore necessary to consider whether the default decision- making mechanism requiring mutual consent should be altered, for instance by providing that the decisions of the joint venture should be passed by a majority vote, by designating a lead member or by specifying bespoke decision-making mechanism for particular situations.

Considering the interest of a contractor joint venture to act quickly and decisively when it needs to, those provisions (e.g. by majority vote or lead member) can be vital as it would allow obstacles to be eliminated within a short timeframe. For example, without such clauses, the only way to seek to expel a problematic member would through an action to dissolve the joint venture for good cause. This in itself might not have the desired effect in that it might jeopardise the contractors’ success in the bid process; such proceedings are also not always straightforward and often time- consuming, which may defeat the purpose of the proceedings.

c) Dispute resolution within the contractor joint venture

Given the fact that it can be essential to solve any material disputes between members of a contractor joint venture quickly, it is advisable to give careful thought to the dispute resolution mechanism in joint venture agreements. This is related to the previous topic of decision- making. It is however an aspect of joint venture agreements that is commonly overlooked or at least not tailored to the specific project or joint venture, largely because discussions on this subject are viewed as being negative at a time when everyone is seeking to establish a positive and co-operative relationship.

Tiered dispute resolution provisions are often included involving referrals to higher levels of management within the joint venture entities to seek to resolve the dispute amicably. Yet, because members of contractor joint venture for complex projects are often established in different countries, international arbitration is by far the most common, final forum for dispute resolution for joint venture agreements; and, for or similar reasons that Swiss law is chosen as the governing law of the joint venture agreement, Switzerland is a common choice for the seat of arbitration. This has its advantages in this context: the “finality” of the arbitral award would be strong because: (i) the award is final from the time when it is communicated (there is no automatic suspension of the arbitral award in case of challenge); (ii) the Swiss Federal Tribunal is the sole jurisdiction to hear challenges of international arbitral award seated in Switzerland; (iii) the grounds to set aside a final award are very limited (the vast majority of appeals are unsuccessful); (iv) the appeals against arbitral award before the Swiss Federal Tribunal are usually decided within six months; and (v) it is now possible to file appeal submissions in front of the Swiss Federal Tribunal in English, even though English is not an official language of Switzerland.

In addition, for certain categories of dispute, it may be appropriate to specify in the arbitration clause that the award must be rendered within a short timeframe and by a sole arbitrator, such as three months from the date of the case management conference for simple issues, and that such a time limit can be extended if necessary. For more complex categories of dispute and for those where there is less urgency in a final decision, different timetable and tribunal provisions can be specified. Either way, it is also recommended to choose a reputable arbitral institution to administer the case in an expedited manner. This would be particularly relevant in the likely case where parties cannot agree on the identity of the sole arbitrator.

Conclusion

For multi-national contractor joint ventures or consortia, the choice of Swiss law to govern their joint venture agreement has advantages. This article has provided some insights on the legal aspects of construction joint ventures and highlights the importance of express provisions for allocating profits and risks, appropriate decision-making processes and selecting dispute resolution mechanisms for joint venture agreements under Swiss law. By understanding these points, contractors can benefit from the advantages of collaborating with other entities and mitigate the potential challenges that may arise in complex projects.

Footnotes

- For the purposes of this article, we assumed that there are no material differences between consortia and joint ventures. The term “joint venture” will therefore generally include consortia.

- Available at: ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics: 2023 – ICC – International Chamber of Commerce (iccwbo.org)

Download a PDF version of ‘Constructing successful partnerships – Swiss Law and joint ventures.’