The Law of Privilege: how it relates to P&I and Defence Clubs

Privilege has long been recognised as a fundamental principle of English law. For several hundred years, the law of privilege has protected the right of clients to communicate with their lawyers in confidence, without fear that those communications will later be disclosed to third parties during the course of litigation. However, the modern commercial context has generated numerous challenges to the law of privilege, most notably for industries in which it is common practice for non-lawyers to advise on legal matters.

These challenges are compounded further by the ubiquitous use of electronic communication and data storage; emails in particular are highly vulnerable to widespread dissemination which may undermine a document’s confidentiality. Even in circumstances where privilege has arisen, it is all too often lost at the click of a button, leaving litigants facing the prospect of disclosing sensitive documents to their adversaries and into the public domain.

This note will outline the current status of privilege from an English law perspective, before addressing some common scenarios particular to P&I and Defence Clubs in which they may run the risk of making communications that lack the protection of privilege.

The current status of privilege The Supreme Court delivered its judgment last month on the most recent case to consider the limited scope of the law of privilege (R (Prudential Plc & Anor) v Special Commissioner of Income Tax & Anor [2013] UKSC1). The judgment serves as a cautionary tale for those across all industries who receive legal advice from non-lawyers. The case concerned tax advice given to Prudential plc by its external accountants, disclosure of which had been sought by the Revenue. The court ruled that because the advice was given by non-lawyers Prudential plc was not entitled to claim privilege. This meant that all relevant communications were fully disclosable, even though the advice was indisputably legal in nature and had it been given by a lawyer there would be no doubt as to privilege attaching.

The Prudential case concerned legal advice privilege, a category of privilege that attaches to confidential communications between clients and their lawyers during the “ordinary course of [the client’s] business”. The Supreme Court’s ruling reinforces the strict rule that only communications between lawyers and members of the “client team” will benefit from the protection of privilege. This contrasts with another category of privilege, litigation privilege, which applies in circumstances in which legal proceedings (such as court litigation or arbitration) have either already commenced or are highly likely to do so. In this situation, communications with third parties will also be safe from disclosure, provided their dominant purpose is linked to the conduct of the proceedings.

The Supreme Court’s decision further entrenched the “client team” concept which emerged from the litigation in the early 2000s between creditors of the collapsed BCCI and the Bank of England (Three Rivers District Council and others v The Governor and Company of the Bank of England [2003] EWCA Civ 474). The Court of Appeal’s highly restrictive interpretation of who exactly constitutes the “client” for the purposes of obtaining legal advice engenders a significant risk to clients even in circumstances where the advice has been given by an external lawyer. Under the rule created by this case, only employees of the advisee client whose role it is to request and receive advice from external lawyers will be able to assert legal advice privilege over those communications.

The meaning of “lawyer” and of “legal advice” has also attracted considerable judicial scrutiny, particularly within the context of in-house counsel. On this issue, English law differs from the position in the majority of European jurisdictions as well as under EU law itself (Thus in circumstances where a company is under investigation from, for example, the EU competition authorities, legal advice privilege will not cover advice from in-house counsel; see Akzo Nobel Chemicals Limited v European Commission [Case C-550/07]), which considers in-house lawyers “insufficiently independent” from their employers to warrant the protection of privilege. However, provided that the communications in question are confidential and concern advice which is legal in nature (as opposed to, for example, strategic or purely commercial), English law will still protect them from disclosure to third parties.

Once a client has obtained confidential advice from a lawyer over which it may safely assert privilege, there follows the enduring challenge of retaining it. This issue underlines the distinction between litigation privilege and legal advice privilege, namely that the former will attach to communications with non-lawyer third parties while the latter will not. Thus if litigation is reasonably in contemplation, imminent or existing, and the purpose of the communications is predominantly connected to the proceedings, litigation privilege will protect both confidential advice obtained from non-lawyers and a lawyer’s advice which the client has then forwarded to a third party.

Conversely in the case of legal advice privilege, the protection from disclosure may be lost if the client shares with a non-lawyer third party the confidential legal advice received from a lawyer. In these circumstances, the client is taken to have waived its right to assert privilege where the extent of the document’s circulation is such that it no longer fulfils the definition of a confidential communication between a client and its lawyer. That third party may even include employees of the same company who are not part of the “client team”. Clients must therefore exercise caution when disclosing parts of documents or documents that form part of a sequence (such as one email in a chain), as it will be open to the other parties in the litigation to force disclosure of the remaining document or documents over which the client will be held to have waived its right to privilege. This last principle applies to both litigation privilege and legal advice privilege.

P&I and Defence Clubs

We set out below some common scenarios which are likely to arise in the course of a Club’s business and which shed light on the numerous threats to asserting privilege over confidential documents.

- A Club claims handler is contacted by members whose vessel has suffered main engine damage. Owners are not sure whether it is because of ongoing problems with their purifier or because the charterers have provided off spec bunkers. The Club claims handler appoints a surveyor, who reports poor maintenance of the purifier has contributed to the degree of engine damage. Is the survey report privileged?

The answer will depend on whether or not litigation has already commenced or is reasonably in contemplation. It is irrelevant that the owners may never commence litigation on account of the surveyor’s findings, only that there is a “real likelihood” or that litigation is “reasonably in prospect”, whether it be as claimant or defendant to an action. A mere possibility of litigation or a general apprehension of future proceedings will not suffice.

In this case, there is a clear and sufficiently realistic likelihood that the owners will wish to claim against the charterers if bad bunkers have also contributed to the engine damage. Moreover, there is a further possibility that the charterers may bring a claim against the owners for off-hire and any other losses. Thus the surveyor’s report would benefit from the protection of litigation privilege.

Notwithstanding the above and assuming that this scenario did not satisfy the “reasonably in contemplation” test necessary to establish litigation privilege, the rule affirmed in the Supreme Court’s Prudential decision would apply and legal advice privilege would not attach to the surveyor’s report.

- After an earlier withdrawal dispute, a Club claims handler advises a member over email on general circumstances in which it would be entitled to withdraw for non-payment of hire. The owners explain they are interested in finding out when they can withdraw as they have a better charter lined up. Are these emails privileged when the member subsequently withdraws a vessel and a dispute arises?

Emails present the law of privilege with a unique challenge. Preserving the confidentiality of emails is considerably more difficult than, for example, letters. This is due to the ease with which emails are circulated, forwarded or copied to third parties, frequently unknowingly or by accident. It is crucial for the entitlement to and maintenance of legal advice privilege that the confidential advice is restricted to members of the owners’ “client team”. Circulation to third parties of these emails or others in the chain may result in the loss or waiver of privilege and the requirement to disclose the full chain of emails.

This scenario would fail the test to establish litigation privilege. At the time it is given, the Club’s advice is generic and not within the context of specific, imminent litigation, thus litigation privilege would not attach to these communications.

In the absence of litigation privilege, the question hinges on the claims handler. If he or she is not a lawyer, the rule in Prudential would apply and legal advice privilege would not attach to these emails. On the other hand, if he or she is a lawyer (i.e. retains a valid practicing certificate and is subject to regulation by the Solicitors’ Regulation Authority or Bar Council), provided the advice is confidential (which it clearly is) and legal in nature (again, this seems certain here), then legal advice privilege will attach to the email communications.

- The Club appoint a London law firm to advise members on a speed and consumption dispute. The London firm suggests the merits are 50:50 and recommends settlement. The Club claims handler forwards this advice to members without copying in the firm, and the claims handler adds in some comments of their own about the merits. Is the email privileged? Is the London law firm’s advice still privileged?

Where an external lawyer advises on the merits of a claim, certainly litigation privilege will apply. The forwarded advice would remain privileged, subject to any subsequent loss or waiver.

Let us imagine, however, that the advice was more generic (in respect of a member’s standard charterparty speed and consumption clause, for example) and that litigation privilege did not apply. The possibility of legal advice privilege attaching will depend on the status of the claims handler.

Assuming he or she is not a lawyer, the act of forwarding the advice to members without the lawyers in copy would run a very serious risk of extinguishing any entitlement to privilege. Even if the lawyers were copied in, widespread circulation by itself may serve to undermine the confidentiality of the document such that privilege is lost forever.

The claims handler’s own comments may attract legal advice privilege provided that he or she is a lawyer, the recipient members are part of the “client team” and the comments themselves are confidential. Beyond this strictly limited scenario, it is probable that the claims handler’s comments are not privileged and their dissemination as an addendum to the law firm’s advice will serve to destroy any claim to legal advice privilege which may have previously attached.

There is scope to assert a further category of privilege in this case, known as common interest privilege. Common interest privilege applies to communications which are passed on to third parties with the same interest in the same matter to which the document relates, which certainly would seem to be the case in this scenario. However, the law of common interest privilege is unsettled and contentious, giving rise to some highly inconsistent case law. It is therefore advisable for clients to avoid exposing themselves to the risk of having to assert reliance on common interest privilege.

- A London law firm obtains a survey report on damage sustained by a vessel after a collision. The Club claims handler writes directly to the surveyor asking questions about the report, without copying in the law firm. The surveyor replies, including information confirming the member’s vessel is likely to bear the majority of the blame for the collision. Is the email privileged? Is the survey report still privileged?

Because there is an obvious real prospect of litigation following the collision, the likelihood is that litigation privilege will cover all of the communications in this example, provided that the report is confidential. In the absence of litigation privilege (i.e. for surveyor reports where litigation is not in contemplation), none of the advice – be it the report itself or the email response – given by the surveyor would benefit from legal advice privilege. As with scenario number (3) above, the comments in the email may serve to remove the legal advice privilege that previously attached to the report when the claims handler received it from the law firm.

- The Club offers new build cover and members ask the Club to comment on the wording of the yard’s refund guarantee and other provisions of the shipbuilding contract. External lawyers have not been appointed to review the contract, but the member is also seeking advice from brokers. The Club representative points out to both the member and brokers a risk that one of the clauses could be interpreted in a way which is unfavourable to the buyer. However, as it is agreed that this is a relatively small risk, it is decided to go ahead and sign the contract. Subsequently there is a dispute in relation to the relevant clause. (a) Is the Club’s advice disclosable? And (b) would privilege still apply if the Club’s advice is accidentally forwarded on to everybody at the member’s new build team, including engineering and operational staff?

At the time of signing the contract, there was no contemplation that litigation would arise. Thus there would be no scope in this scenario to assert an entitlement to litigation privilege. If the Club’s representative is not a lawyer, then the rule in Prudential will apply and the Club’s advice to both members and brokers will not be protected by privilege. Even if the Club’s representative were a lawyer, dissemination to the entire new build team would almost certainly be fatal to a claim for legal advice privilege.

- A shipowner’s company-wide reporting system stores accident investigation reports on a database accessible by all employees in the office. Would these reports be privileged?

Whether litigation privilege would apply or not would depend on the circumstances, but the most prudent approach would be to consider that it does not. This is because the preparation and preservation of accident reports is a general procedural step performed in order to ensure safe operating practices, thus it cannot be said that specific reports serve the interests of litigation as their dominant purpose.

As the reports’ draftsmen are not lawyers, it is unlikely that legal advice privilege will attach either. The lack of confidentiality to a “client team” connected to any claims which may arise from accidents reported on the database vitiates further any entitlement to claim privilege in this example.

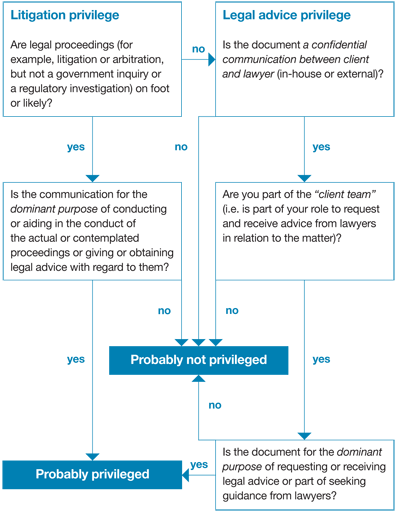

The following flowchart illustrates the way in which the courts will determine whether or not a document may be protected by privilege.

Conclusion

This note has covered some of the obstacles and pitfalls that may undermine an entitlement to privilege. Clubs must therefore exercise abundant caution in order to safeguard their confidential communications against disclosure to third parties during the course of litigation, both by as far as possible ensuring that the advice they receive is privileged in the first place, and preserving that protection permanently.

For more information, please contact Paul Dean, Partner, on +44 (0)20 7264 8363 or paul.dean@hfw.com, or your usual HFW contact.

Download a PDF version of ‘The Law of Privilege: how it relates to Pu0026I and Defence Clubs’