Is there a notable initiative in a market that can be developed into a Pan-Arab initiative? April 2018

To a great extent banks and insurers are the “yin and yang” of operational risk. Banks have to deal with operational risk on a daily basis. Banks attempt to manage and mitigate these risks; and when they cannot, banks may attempt to transfer these risks to the insurance and reinsurance market. Insurers, for their part, attempt to understand and price the risk and then, in effect, remove that risk from the bank’s balance sheet. The premise of this paper is that banks and insurers have much more in common than meets the eye and that new developments in their respective markets can significantly enhance the financial strength of the Pan-Arab region.

In recent times, banks have sought to analyse operational risk on a granular basis and then map these risks into their insurance programmes. Insurers, for their part, have sought to analyse and assume the risk (if possible). The process of risk transfer between banks and insurers has been ongoing for over a century since the Lloyd’s Bankers Blanket Bond was first issued. Further risks were transferred as markets, liabilities and technologies developed (although the level and amount of transfer has ebbed and flowed over the period).

Before examining the initiatives which are occurring in the markets and how they can be developed into a Pan-Arab initiative, one first needs to briefly examine (a) bank operational risk and (b) the methods of transferring the risk.

Operational Risk

Operational Risk is “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events. The definition includes legal risk1, but excludes strategic and reputational risk”.2 Operational risk falls into broadly seven categories3:

- Internal fraud – employee infidelity (including “rogue” and insider trading), market manipulation, theft of information, money laundering.

- External fraud – theft, advancing funds on forged documents, cheque kiting, computer crime (including hacking), web page “defiance”

- Employment practices – health and safety, discrimination.

- Client, products and business practices – negligent advice, breach of privacy, misuse of confidential information, improper and/or aggressive sales.

- Damage to physical assets – natural disasters, property damage.

- Execution, delivery and process management – delivery failure, loss of client assets, vendor disputes, collateral management failure, data entry error, incorrect client records.

- Business disruption and system failures – hardware, software issues, utility outages.

As can be seen, many of the activities which fall within these categories are capable of being insured – for example, under a Bankers Blanket Bond, Computer Crime, Professional Indemnity or Cyber Crime Policy. Other risks are more “indirect”, but nevertheless impact a bank’s balance sheet; for example, employment practices, directors’ and officers’ liability (and the insurance of the latter would, one might expect, attract people of a necessary calibre, to provide the necessary governance to the bank and risk management supervision). Not only are the risks capable of being insured, but the insurance market has a significant, cumulative experience which it can bring to bear – given the benefits of a subscription market and the fact that insurers will have multiple exposures to and experiences of different banks (losses, claims and banking activities).

Market Initiatives

So, how is the market changing and what initiatives could benefit the Pan-Arab region?

First, a bit of history. In 2004 the Basel Committee reported on the role insurance could play from a banking/risk management perspective4. The Basel Committee was a gathering of cautious banking individuals (and they were not insurers). Their main finding was that banks adopting the Advanced Measurement Approach (AMA)5 could use their insurance policies (if the insurers or reinsurers were suitably credit rated) to replace part of their operational risk capital (i.e. part of the bank’s Tier One capital which it was required to retain on its balance sheet to cover operational risks). The findings of the Basel Committee were colloquially known as “Basel II” and had a global application.

Basel II policies required little “tweaking”; for example, the policies, at any point in time, needed to have an unexpired 12 month period (this was achieved by writing two year policies which were cancelled on the first anniversary and then renewed for a further two years). So the actual products were not changed significantly and, more importantly from the insurers’ perspective, coverages were not widened6. The bank got a dual benefit: risk transfer to the insurers and an operational risk regulatory capital discount. But, given this was insurance, banks could not take 100% of their policy limits on their balance sheets to replace their capital – only up to 20% of the policy limit was permitted (“the oprisk haircut”). For the rest of the banks adopting the basic or standardised approach to operational risk (i.e. a less sophisticated approach), in principle, no capital relief was permitted.

As we all know, by 2008/9 we had the Global Financial Crisis which put an immediate stop to any developments in this area (although a considerable amount of time had been expended by lawyers, brokers, banks and insurers in bringing these products to market)7. Further, one of the problems with Basel II was that it had been authored by bankers and not insurers. Therefore issues such as contract certainty, coverage triggers (claims made, discovery based, loss occurring), first and third party liability claims, duties of disclosure and reinstatements were never addressed. However, by 7 October 2010, the Basel Committee had fathomed these issues8.

Scroll forward three years and the old documents were dusted off and were revisited and some (re)insurers and banks started to assemble insurance programmes. One of the first to be assembled was the Dresdner Bank programme and tucked away on page 184 of its 2013 accounts was the following:

“We buy insurance in order to protect ourselves against unexpected and substantial unforeseeable losses. The identification, definition of magnitude and estimation procedures used are based on the recognized insurance terms of “common sense”, “state-of-the-art” and/or “benchmarking”. The maximum limit per insured risk takes into account the reliability of the insurer and a cost/benefit ratio, especially in cases in which the insurance market tries to reduce coverage by restricted/limited policy wordings and specific exclusions.

We maintain a number of captive insurance companies, both primary and re-insurance companies. However, insurance contracts provided are only considered in the modelling/calculation of insurance-related reductions of operational risk capital requirements where the risk is re-insured in the external insurance market.

The regulatory capital figure includes a deduction for insurance coverage amounting to €522 million as of December 31, 2013 compared with €474 million as of December 31, 2012. Currently, no other risk transfer techniques beyond insurance are recognized in the AMA model.” [Author’s emphasis.]

So, as can be seen, use of insurance products can produce quite significant returns and can release regulatory capital which would otherwise be “frozen” and unproductive. There is no reason to believe that the policy structures departed significantly from established wordings, although the attachment points for the insurance programme were likely to be relatively high (we are talking several hundreds of millions of dollars or euros). And whilst pre-Global Financial Crisis “oprisk haircuts” were in the region of 10-15%, currently they are upwards of 20% i.e. the full reduction.

What the Basel Committee did forewarn was that these programmes were not meant to function as capital arbitrage i.e. the bank was required to demonstrate to its regulator that its “recognition of the risk mitigating impact of insurance reflects the insurance cover in a way which is consistent with the likelihood and impact of the losses that the institution may potentially face.”

A number of other banks followed suit, although it is fair to say there was not a torrent of activity.

So how were banks achieving these capital reductions? What new and sophisticated product had insurers produced to achieve these ends? As noted above, no new product was produced (certainly in coverage terms). Admittedly, some of the old “wrinkles” were smoothed out. Policy programmes were integrated and updated (who can forget that it was not until recently that the computer crime wording was updated, and did away with tested telexes!). Professional indemnity programmes switched to civil liability programmes. And some covers which previously had not been purchased were now included as a matter of course e.g. unauthorised trading cover, cyber cover.

However, whilst the coverages were not expanded, the real issues for the banks and insurers were twofold:

- mapping how insurers recognised claims and losses and how banks recognised the same. If one examines a claims made policy (where the policy period reflects, generally, the annual venture for insurers), then when a claim which is made in one year results in further related claims once the policy has expired, those claims are referenced back to the first notified claim and the expired policy. Banks, when raising provisions, do not apply the same methodology – if claims stretch across several years they are more inclined to raise provisions on a yearly basis. It is recognising the tension between these methodologies that remains the biggest (but achievable) challenge.

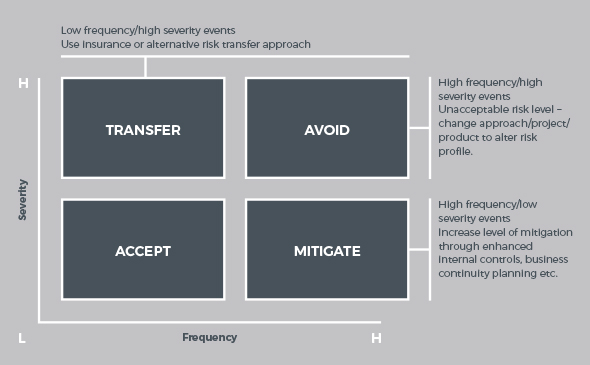

- how banks and insurers identify the risks which are capable of transfer and which risks should be retained. This can be illustrated simply by way of the diagram below:

How to import the initiative

But, you ask, how does this initiative translate to a Pan-Arab initiative? Let us consider the baseline issues.

First, there are not a sufficiently large number of banks in the region to benefit from such structures. The banks which could benefit from insurance products would need to adopt the AMA approach which would require those banks to have in place sophisticated (and expensive) systems in order to monitor operational risk. No systems – no regulatory capital discount. However, (a) there are a few banks with the necessary size to benefit from such structures (and consolidations appear to be increasing) and (b) replacing some bank’s capital with insurance might well be more economic. In other words, partial reductions may be possible. What this is, put simply, is a costs arbitrage between the bank’s cost of capital (or put another way, if the capital was released what return would the bank achieve with it) and the premium paid for the policy (but not a capital arbitrage which the Basel Committee said was a “no-no”). Looking at the diagram above, it might be appropriate for the banks to transfer some risks and not others.

Second, the regulators will have to sign off on these deals; but this is good for banks and the whole financial environment. Regulators (who tend to be naturally and understandably conservative given the travails of recent history) will only sign off if they are satisfied that (a) the risk is fully understood and (b) the risk is properly transferred to insurers and reinsurers of a suitable rating. And an appropriate (strong) rating is essential – the over capacity of reinsurance capital globally does not mean that these programmes can work as a matter of course – good quality capital is required, well underwritten and claim/loss payments should be made speedily. The latter issue is central – slow payments (or worse non payment) render any insurance product from the banks’ perspectives useless.

Third, the author is already seeing certain, sophisticated (but non AMA) banks in the region, model their insurance programmes on those of their European counterparts. Accordingly, the acceptance and understanding of such programmes and how they function is growing (supported by a number of leading brokers).

Benefits of these products and disciplines

So what of the banks which cannot avail themselves of the use of such programmes (i.e. non AMA banks)? There is no reason why such products and underwriting methodologies cannot be applied and the benefits of such applications are explored below.

First, the new products now reflect new banking practices, risks and paradigms. And, new products are also being developed which now cover risks which have previously been excluded: for example, coverage for commodities documents such as bills of lading and warehouse receipts (for the trade finance department). However, the corollary is that such coverages are not available to all – if banks wish to purchase these policies then there has to be (a) a fair allocation of responsibility and risk management and (b) the proper provision of information. This immediately impresses on banks the need to up their game in terms of best practices – if the bank improves its risk management, the likelihood of purchasing these products (at a decent premium) increases.

Second, to date, the underwriting of risks has been handicapped by the asymmetry of information i.e. banks have a considerable amount of information (even for non-reportable losses/claims) whereas insurers have very little (albeit considerable experience of losses/claims). Risks are often underwritten with an astonishingly small amount of information; for example, a US$25 million crime cover may be written on the back of a completed proposal form accompanied by the last annual accounts (at best there might be a presentation to insurers given by senior executives at the bank!). If the risk is going to be underwritten and priced properly and there is going to be a fair and proper risk transfer, information flows need to improve. Banks need to create more accurate and efficient systems for capturing information and insurers need to interpret it properly. And, in underwriting the risk on this basis, insurers have the ability to influence the bank’s risk management and information systems: put simply, if the information is not up to scratch, then no risk transfer can occur.

But, you ask, if the bank is not prepared to establish a satisfactory risk management framework (as required by insurers), won’t the bank simply go to another, less concerned insurer (and possibly less robust)? Yes, that is a possibility, but as we have seen, there tends to be a correlation between good underwriting and the credit rating of the insurer. One of the tools for banks in assessing risks is credit ratings – why should they not apply similar processes when it comes to the transfer of their own balance sheet risks?

What other benefits can be provided to banks other than the financial impact of the use of insurance?

- Loss control and risk management services can be provided by insurers and specialist brokers; after all, they are at the “front end” when it comes to claims and losses. The “experience accounts” which have built up over decades can now be put to use – after all, they have paid losses on Enron, Sumitomo, Barings, WorldCom, Madoff, Stanford, systemic asset stripping in Scandinavia and South Africa … to name but a few. In this regard, let’s consider some simple examples of how insurers might impact and their experience which they can bring to bear

- It should be remembered that losses occur sometimes for quite simple reasons. Insurers are privy to these reasons because they pay claims and losses. For example, a US bank suffered losses of several hundred million dollars incurred by a $:¥ trader. How did this situation arise? It was because the bank was too mean to pay for two Reuter’s feeds (one for the front office (trader) and one for the back office). The trader settled all his own accounts and the back office never verified any of the deals (the bank would not pay for the back office employee to call traders in the Far East to verify the deals). If five random deals had been selected, the fraud would have been uncovered. At the time, given the bank indulged in proprietary trading insurers offered an unauthorised trading policy; the bank declined the policy saying it was too expensive and, after all, it would never happen to them…

- Another more intuitive example was told to the author. A US/Swiss bank collapsed because it was found to be operating a Ponzi Scheme. When insurers were invited to visit the bank in Geneva they met the chairman at his home. On departing his home, on the way to the bank premises, the banker and the insurers turned left for the bank premises. One insurer had expected the group to turn right, to that part of Geneva where the banking community was situated. Just based on this geographic “mis-step” that one insurer declined the risk (and avoided the $60 million loss which his fellow insurers had to pay).

- The cost and availability of insurance in of itself may act as an incentive to reduce losses and to establish adequate risk management processes.

- When profiling the risks decisions will have to be taken as to whether to transfer the risk or retain and manage the risk (see the diagram). Having analysed the risk environment it might be more cost effective for the bank to retain and manage certain risks rather than transfer them to the insurance market. Certainly some of the programmes which the author has reviewed have only insured, for example, first party risks (e.g. crime and property damage), whilst liabilities to third parties (generally insured under a Financial Institutions Professional Indemnity Policy) remained uninsured.

- With insurers engaging with the banks they can provide products which are more reflective of the underlying risks. This also reduces the possibility of costly and lengthy underlying coverage disputes arising – these are not helpful from the perspective of reputation, regulation or plugging operational risk balance sheet “holes” in a timely fashion9. Moreover, the alignment of the occurrence of events and the response of insurances needs to be rationalised i.e. a particular loss event may impact a number of policies – again, a recipe for uncertainty. Until recently, the failure of banks and insurers to “stress test” policies with scenarios resulted in considerable uncertainty. The asymmetry of information did not assist, although software is now available to analyse risks and place them in the appropriate operational risk “buckets” (see pages 1 and 2).

- With insurers engaging properly in the risk transfer they will accumulate a better understanding of the risk (and the author does not buy in to the notion that bank’s will seek to protect their IP when it comes to providing information – sophisticated insurers (which have the same financial reporting requirements and structures as banks) will be able to capably understand the bank’s mechanics and processes). This leads to an alignment between the bank’s operational risk teams and insurers (and the development of a more partnership based relationship). Insurers can now stress test the loss/claim scenarios. Accordingly, products which are produced are far more accurately aligned with the risks.

- And, there is already an established precedent for this form of underwriting where banks use insurance products for unfunded credit risk mitigation: it’s called trade finance/credit insurance. These risks are already being underwritten in the region and the expertise already exists. The reasons why banks purchase such products (or are co-insureds where customers obtain such products as part of their security package presented to the bank) is that banks can get capital relief. Banks “get it” and the reason they do is because it is the deal teams which assemble the deals, calculate the figures and can see whether it is more cost effective to transfer the risk (i.e. payment of the premium) rather than fund the cost of capital/cost of credit risk. For those teams it’s simple economics, it is not a procurement spend (which is the imperative for operational risk insurance buyers i.e. the same products and limits purchased every year with perhaps an increase in the D&O limits).

And why are these products so effective and sought after? Quite simply, they offer certainty of cover and payment. The policies map into the risk accurately, they contain little exclusionary language10 and there is relative certainty of timely payment The product has little relevance if payment is delayed. Finally, the dispute mechanism is intended to fast track the process in the unlikely event that a dispute arises11. - In addition, the other effect of insurance is to de-risk capital. On this basis, why should these products be limited to banks – why not corporates with treasury functions? Moreover, if bank corporate clients are purchasing trade credit policies and offering these as security to banks, are they not de-risking the capital which the bank is providing and, hence, the cost – if so, should not bank clients benefit from the reduction in cost and the competitive nature which such structures would achieve between banks?

- On a regional basis, particularly somewhere like the UAE, it might be possible to mutualise the risks, providing meaningful limits to maximise risk transfer and/or cost of capital. Alternatively, banks (and corporates) could consider the establishment of captives. With forethought, the full panoply of insurance structures which have been trialled elsewhere (and have worked), can be brought to bear. In addition, local risk/regional structures can be integrated e.g. Takaful.

- With the development of a regional insurance and reinsurance structure, risks can be retained and managed within the region. Such developments would build up a cadre of experts (in the banking, insurance and broking sectors) in the region who understand the risks and can produce insurance programmes which accurately reflect the risks (how many times have issues arisen where plain vanilla London form wordings are used without “localising” the wordings)12.

- With a cadre of experts, disputes can be resolved locally. Courts can call upon acknowledged experts to assist them and arbitrations can be held without having recourse to experts outside the region (with the attendant reduction in costs and time).

Conclusion

It is clear that there is a growing understanding of how these insurance products work and the dual uses to which they can be put – no longer is it a question of simple risk transfer (indeed, on some of these significant programs risk transfer is furthest from the CFO’s/risk manager’s mind – it is the costs arbitrage which is the primary objective). The products and the providers of these products have the ability also to change the system, regional business cultures and values. The alignment of insurers and banks can lead to considerable mutual benefits (and profits) for these entities and also release capital to stimulate the regional economy. Moreover, and just as importantly, the benefits to those banks which cannot achieve (selected) regulatory capital reductions are still tangible in promoting greater cooperation between insurers and banks and upping their game across the region.

It is acknowledged that this re-alignment of interests will not occur in the short term. However, it is fair to say that programmes are developing along these lines and it is inevitable the rate of development will increase in the medium term.

John Barlow

Partner, Dubai

T +971 4 423 0547

E john.barlow@hfw.com

Footnotes

- Legal risk encompasses unforeseen legal developments and the failure to comply with supervisory requirements (which may involve fines and penalties (which themselves may not be capable of being insured)).

- “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, para 644”.

- These categories are derived from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision analysis – on which more later.

- “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards”. An updated version was issued in June 2006.

- The AMA approach comprises three strands:

1. The board of directors and senior management are involved actively in the oversight of the operational risk management framework;

2. The operational risk management system is conceptually sound and implemented with integrity; and

3. There are sufficient resources to implement the system. - There is clearly a delicate balance to be drawn between the risk transfer between balance sheets of banks and insurers, potential issues of aggregation and systemic issues – to a great extent, a diverse, subscription market assists in addressing these issues.

- The products were either wholesale re-writes of existing products (which found few takers, the banks being naturally conservative creatures, at least with regard to the purchase of insurance products), or the “tweaks” as mentioned. More recently, programmes are beginning to function as a form of contingent capital, albeit operating within the confines of standard policy wordings.

- “Recognising the Risk-Mitigation Impact of Insurance in Operational Risk Modelling”.

- By way of a real example, the author when investigating bank losses in South Korea, remarked that the vanilla crime policy did not effectively map into the risk environment and was told by the broker that this was the wording which was always used and if claims were declined then they would simply blame the London reinsurance market!

- They will generally contain nuclear (if London market wording, although its presence is quite inexplicable) and fraud exclusions.

- Indeed, certain products “write in” the expert to which the insured and insurer can refer matters for a speedy response.

- An obvious example which springs to mind is the negotiability of cheques – they are negotiable in the UAE; they are not in the UK. The negotiability of such instruments immediately changes the risk environment. It does not mean that such risks cannot be insured, but the necessary safeguards need to be in place to ensure that minimum standards are recognised when handling such instruments. This is simply allocation of risk and what the bank needs to understand is that if it does not manage the risk properly, it will not be covered. Banks are experts in authoring internal manuals in order to manage and control risk; the problem has always been ensuring staff compliance with such manuals.

Download a PDF version of ‘Is there a notable initiative in a market that can be developed into a Pan-Arab initiative? April 2018’