Egypt protests: issues for shipping

The situation is dynamic and this briefing seeks to identify some of the issues which shipowners and others who regularly call at Egyptian ports should have in mind. We focus on charterparties, but similar issues will arise under other contracts of affreightment and bills of lading.

Almost three weeks after protests began in Egypt, President Hosni Mubarak stood down on Friday 11 February, handing control of the country over to the military. There is still considerable uncertainty as to how the situation will develop, and at present the military are likely to remain in control for six months or longer.

The situation is dynamic and this briefing seeks to identify some of the issues which shipowners and others who regularly call at Egyptian ports should have in mind. We focus on charterparties, but similar issues will arise under other contracts of affreightment and bills of lading.

Are the parties entitled to refuse to perform a charter by reason of frustration or force majeure?

A contract will be frustrated where there is an unforeseeable change of circumstances which either makes a contractual obligation incapable of being performed or which renders performance radically different from that which was undertaken. Mere inconvenience, hardship or financial loss will not amount to frustration, and, generally speaking, it is very difficult indeed for a party to establish that a contract has been frustrated.

Depending on the specific provisions in the charter, owners may be able to argue that performance has been discharged by force majeure and/or Act of God provisions. Force majeure is not a free-standing principle of English law, and parties will need to consider carefully the terms of their contracts, to see which force majeure events are identified in the relevant contract, and whether the events in question actually fall within the parameters of the clause.

What if the Suez Canal is closed?

We understand that the Egyptian Army is controlling the Suez Canal, which has remained open throughout the protests. If the Suez Canal were to be closed, then vessels would, of course, need to follow the alternative route around the Cape of Good Hope. This is likely to take, on average, an additional ten days, and lead to significantly increased bunker costs.

Closure of the Suez Canal is unlikely to amount to frustration of a time or a voyage charter on grounds of increased cost or delay.

In a time charter, charterers will, of course, pay hire for the extra time spent travelling via the Cape of Good Hope, and it is likely that they will also be paying for the bunkers.

Parties to voyage charterers and bills of lading will need to look carefully at the terms of those documents to assess who is liable for the additional costs of an extended voyage.

Are owners entitled to refuse to call at Egyptian ports?

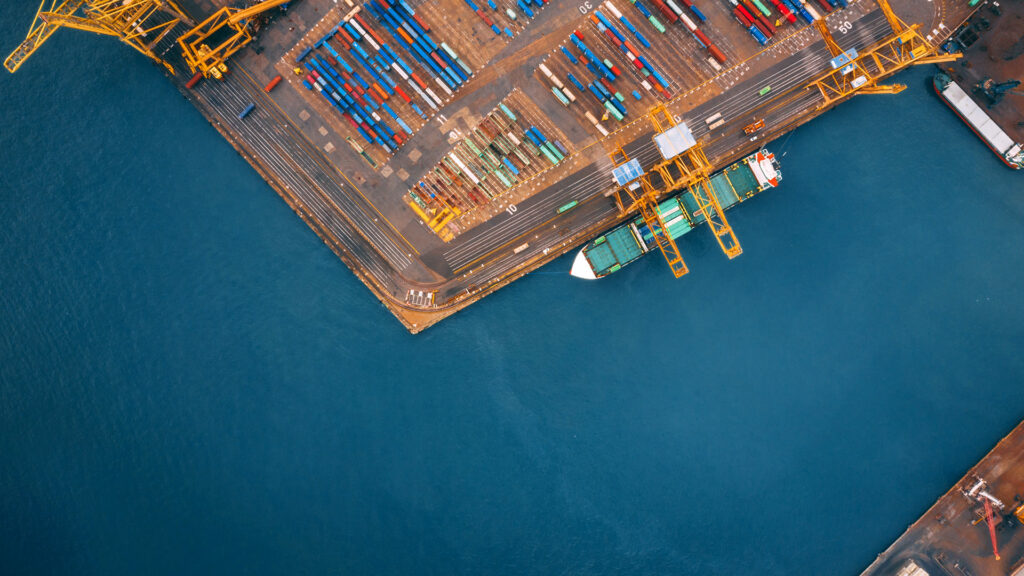

During the protests, some major operators refused to call at some Egyptian ports, and one leading container line declared Egypt’s Port Said to be closed because of rioting. There were also widespread strikes (including a strike by workers at the Suez Canal) although it is understood that the military government are now taking steps to make future strikes less likely.

It is expected that there will be continuing congestion at ports, following events over the past three weeks. For example, there were reported shortages of staff and customs officials at Alexandria and Damietta. Owners will not be able to rely on these staff shortages as grounds to refuse to call at these ports.

If the situation deteriorates, issues may arise as to whether particular ports are safe, whether ports fall within the trading limits in the charter and whether owners are entitled to deviate to another port.

At this time, there is nothing to indicate that Egyptian ports are not safe in the legal sense. A port is safe if ships can reach the port, use it and return from it without, in the absence of some abnormal occurrence, being exposed to dangers which cannot be avoided by good navigation and seamanship.

Where a port is legally safe, but there is ongoing disruption there, owners may seek to argue that they do not need to call there, by reason of the trading limits set out in the charter.

Owners will look first at the express trading limits in the charter. If the port does not fall outside the express trading limits in the charter, then the parties need to consider whether the port, whilst safe, is excluded from the trading limits by reason of war, riot or insurrection. One important issue to consider is whether there has been a significant increase in the risk since the charter was signed, or whether this was a risk which the parties agreed to bear at the time the charter was signed, in which case owners will find it difficult to rely on one of the general exclusions from the trading limits.

Owners will also have to review the charter carefully to identify whether they are entitled (by reason of an express clause) to deviate to an alternative port. If so, they need to ensure that they comply with any requirements of that clause, and also that they act properly and as required – ie in good faith, not arbitrarily, capriciously or unreasonably.

If there is no express right to deviate, owners may seek to rely on the implied right to deviate to save life/property and/or an argument that this is a “reasonable deviation” under the Hague Rules.

Who pays for the delays?

If there are delays to shipments to or from Egyptian ports, eg because of further strikes, then the question will arise as to whether owners or charterers must pay for those delays.

In the case of a time charter, charterers will seek to argue that the vessel is off-hire, in order to suspend their obligation to pay hire. The specific off-hire clause needs to be carefully considered, but if the charter incorporates one of the usual off-hire clauses (such as NYPE clause 15), then charterers will find it difficult to argue that the vessel is off-hire.

In the case of a voyage charter, laytime will run (assuming that the vessel has been able to tender valid Notice of Readiness). However, depending on the circumstances (and the specific clause in question), charterers may be able to rely on one of the exceptions to laytime, in order to stop laytime from running. Charterers’ position will be more difficult if the vessel is already on demurrage, as the exceptions are.

Who pays for the other costs?

If carriers are entitled to deviate, they may also be entitled to recover the additional costs from cargo interests. The terms of the clause which gives owners the right to deviate must be carefully considered.

Any additional costs or losses incurred by owners as a result of following charterer’s orders may also be recoverable under an express or implied indemnity (or by way of a claim for damages if orders were illegitimate.

The events in Egypt could further increase war risk premiums, which are already at an increased level, because of the effect of piracy. If war risks premiums are further increased, owners should carefully consider the terms of their charters, to see whether they are entitled to recover any additional costs by way of additional charges to charterers.

There has also been speculation about increases in Suez Canal dues by any new Egyptian government, to fund state spending. Additional charges of this kind will not frustrate the charter. As with war risk premiums, the terms of the charter need to be carefully considered to assess whether the charterers must pay any such additional costs, if and when they levied.

What is the effect of closures of local banks?

Closures of commercial and public banks have been reported. This may lead to problems in respect of payments under sales contracts, which will usually be by way of letters of credit.

In addition, any time charterers who are reliant on Egyptian banks to make payments of hire must take appropriate steps to ensure that hire is paid in full and on time in order to avoid the risk of withdrawal of the vessel. If there is a delay in payment, owners should carefully consider the withdrawal provisions in the charter (particularly any anti-technicality provisions) before taking any further action.

What other practical issues need to be considered?

Port agents and local correspondents will be able to provide up to date information on developments “on the ground”, and we recommend that they are consulted if owners or charterers have particular concerns.

For example:

- Those running on tight timetables (eg “just in time shipments”) will need to make allowance in their schedules for potential delays.

- Those who store goods in warehouses in Egypt need to consider whether those goods are adequately insured.

- If cargo is re-routed, the carrier will need to decide whether they are entitled (and whether they feel commercially able) to pass on to their customers any additional terminal handling charges, transhipment costs and freight costs which are incurred.

For more information, please contact Daniel Martin, Associate, on +44 (0)20 7264 8189 or daniel.martin@hfw.com, or Scott Pilkington, Associate, on +44 (0)20 7264 8323 or scott.pilkington@hfw.com, or your usual contact at HFW.