Construction Bulletin, March 2022

In this Construction Bulletin we cover a broad range of recent developments in international construction law, including: Judicial Approach to Uncontroverted Expert Evidence: Griffiths v Tui; “Jurisdiction vs. Admissibility” in Hong Kong Arbitration Law; Security for Joint Venture Participants; Ensuring Arbitration Provides an Alternative Dispute Resolution Process; Upcoming events

Judicial Approach to Uncontroverted Expert Evidence: Griffiths v Tui1

Is the court obliged to accept uncontroverted expert evidence? The answer is no. This briefing explores the Court of Appeal’s decision concerning expert evidence, which is very important in construction claims. The rules are applicable to both arbitration and adjudication for construction claims and relevant in jurisdictions with similar rules2 including Hong Kong3.

Background

Mr. Griffiths purchased an all-inclusive holiday from TUI. He suffered serious gastric illness whilst on holiday. His symptoms persisted after his trip. He alleged that his illness was caused by his consumption of food or drink at the hotel.

At trial, the only expert evidence addressing causation was the report of Professor Pennington (Mr. Griffith’s expert) and his answers pursuant to CPR Part 35. Professor Pennington was not cross-examined and no evidence was called to challenge his report.

The expert report was described as “minimalist” and deficient. The claim was dismissed because the court was not satisfied that the expert evidence showed that Mr. Griffiths’ illness was caused by contaminated food or drink from the hotel.

The appeal 4 was allowed by Spencer J. The second appeal raised the question of whether the court can evaluate and reject an uncontroverted expert’s report.

Decision

The second appeal was allowed 5 because: (1) there is no strict rule preventing the court from considering the content of an expert’s report though compliant with CPR Part 35 but is not challenged; (2) it is not inherently unfair to challenge expert evidence in closing submissions provided that the expert’s credibility is not challenged; (3) the onus is on the party relying on the evidence to ensure that the content of the report is sufficient to discharge the burden of proof; and (4) a rigid test based solely upon whether the requirements of CPR Part 35 have been met is inappropriate, and this alone is insufficient to require the court to accept such evidence.

Lessons Learned

A party seeking to rely upon expert evidence must ensure that the report not only meets the minimum threshold of CPR Part 35 but also contains the expert’s full reasoning for the conclusion.

Take care when considering the format of expert reports. Failure to set out the reasoning might diminish the weight to be attached to the report.

It is a “high risk” strategy for not calling any expert evidence, or cross-examining an expert, but to reserve criticisms until closing submissions as this may be regarded as litigation by ambush.

Stephanie Yu

Senior Associate, Hong Kong

T +852 3983 7658

M +852 9175 9698

E stephanie.yu@hfw.com

Footnotes

- Peter Griffiths v TUI (UK) Limited [2021] EWCA Civ 1442 (“Griffiths”).

- Part 35 of the Civil Procedure Rules (“CPR”) and Practice Direction 35 (Experts and Assessors) which governs the use of evidence from experts and assessors in civil proceedings in the UK.

- See Part IV of Order 38 of The Rules of the High Court (Cap 4A) and Appendix D (Code of Conduct for Expert Witnesses) which governs the use of expert evidence in Hong Kong

- Mr. Peter Griffiths v TUI UK Limited [2020] EWHC 2268 (QB).

- By majority (2-1) however, the Court of Appeal’s decision may not be final despite refusing permission for Mr Griffiths to appeal to the Supreme Court. In light of the strong dissenting comments of Bean LJ at [98] and [99], Mr Griffiths may appeal further to the Supreme Court – watch this space.

“Jurisdiction vs. Admissibility” in Hong Kong Arbitration Law

Recent cases1 confirm that arbitration agreements governed under Hong Kong laws are now subject to the concept of “jurisdiction vs. admissibility”, which concerns whether and if so when claims can proceed to arbitrations. This briefing explores the legal concept and sets out its implications to construction claims.

Terminology Explained

It is common for parties to construction contracts to incorporate multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses, i.e. when a dispute arises, parties resolve the dispute in stages. A classic example: parties agree to first negotiate and/or mediate, failing which they will proceed to arbitration when the project is completed. These are known as “conditions precedent” ( CP), and must be complied with before commencing an arbitration.

Very often, parties hold different views on whether CPs are fulfilled. When one party attempts to commence an arbitration, the other party may challenge its validity and request the arbitral tribunal to make a preliminary ruling on whether it has “jurisdiction” to hear the dispute.

The tribunal may rule that it lacks jurisdiction. “Jurisdiction” concerns the power of the tribunal to hear a case. It relates to the existence, scope and validity of the arbitration agreement, and whether arbitration is the appropriate forum. The lack of jurisdiction, if so ruled, is permanent.

The tribunal may rule that it has jurisdiction, but the claims are inadmissible. “Admissibility” concerns whether it is appropriate for the tribunal to hear the claims. The bar is, in principle, temporary and may be removed, e.g. once CPs are fulfilled.

Recent Hong Kong Cases

Recent Hong Kong cases confirm that non-compliance with conditions precedent to arbitrations goes to “admissibility” of the claims rather than the arbitral tribunal’s “jurisdiction”. The distinction between “admissibility” and “jurisdiction” was not considered in Hong Kong Courts before.

In C v D, the Court held that non-compliance of the CP concerned – a request in writing for negotiation in good faith – goes to admissibility not jurisdiction. The Court held that the tribunal does not lack jurisdiction to make the arbitral award, notwithstanding the Plaintiff’s challenge to the non-fulfilment of the CP, which (it argues) would render the tribunal lacking jurisdiction to do so. Kinli subsequently endorsed C v D.2

T v B offers an important perspective to consider the same question. Does the above still holds if complying with the CPs concerned may lead to a limitation defence against the relevant claims, because the construction project is ongoing and the causes of action arose at an early stage of it? The Court’s answer is still “yes”, adding that in such a scenario, it only means the relevant claims are at risk of being time-barred. The Court considers that this is a “contractual risk” accepted by the parties when they entered into the contract.

One workaround, as suggested by C v D, is that parties may agree that pre-arbitral CPs should go to the tribunal’s “jurisdiction” but such agreement requires clear and unequivocal language3.

Implications

Following the recent cases, the Hong Kong Court’s approach is now consistent with common law jurisdictions such as England and Wales 4, the US5, Singapore6 and Australia7. Whilst this may provide some certainty to contractors running Hong Kong projects, stakeholders should be wary of the contractual risks regarding limitation defence, especially if the projects concerned would last for years.

Footnotes

- C v D [2021] 3 HKLRD 1, Kinli Civil Engineering Ltd v Geotech Engineering Ltd [2021] HKCFI 2503 and T v B [2021] HKCFI 3645. HFW acted for T in T v B.

- In Kinli, Mimmie Chan J clarified that the question as to when arbitration can be commenced is a matter for the tribunal to decide, if the Court is satisfied that an arbitration agreement exists; see [33].

- See C v D at [52], T v B at [23].

- See Sierra Leone v SL Mining Ltd [2021] EWHC 286 (Comm) and NWA v NVF [2021] EWHC 2666 (Comm).

- See BG Group plc v Republic of Argentina 134 S Ct 1198 (2014).

- See BBA v BAZ [2020] SGCA 53.

- See Nuance Group (Australia) Pty Ltd v Shape Australia Pty Ltd [2021] NSWSC 1498.

Security for Joint Venture Participants

Partnering up for project delivery, both in the construction and operations phases, is now common. While the focus during the bid phase is inevitably on the project documents and winning, there is still a significant amount invested in trying to put mechanisms in place that will govern the delivery relationship – such as ‘’joint venture’’ (JV) organisation structures, responsibilities, procurement, financing requirements and distributions, and the decision making processes (and managing deadlocks).

The participation interest that each party has in the JV is often negotiated after careful consideration of financial risk and return. What is often overlooked, and is the focus of this article, is the security that JV members should obtain from other consortium members, to ensure that their interest is protected.

For the reasons set out below, we conclude that an all-party cross indemnity should be considered in most projects.

The Project Scenario

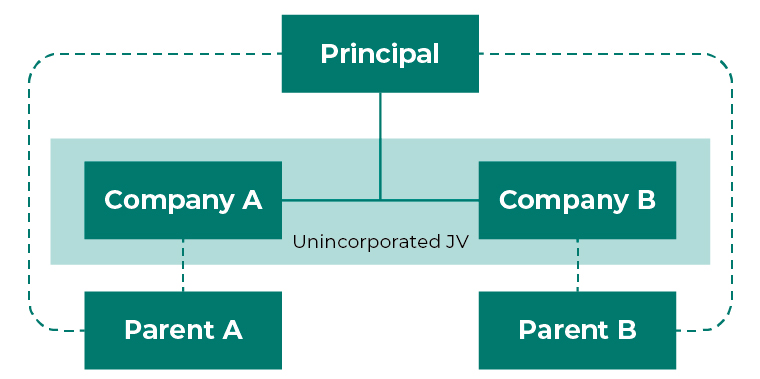

This briefing considers a simple JV comprised of two participants in an integrated unincorporated JV where each of the participants is a subsidiary of a larger parent organisation. These principles are also applicable to larger structures, where the reason for obtaining adequate security is more compelling.

The Principal will enter into a project agreement with Company A and Company B (the Project Agreement). The Principal will also request a parent company guarantee ( PCG) from each of Parent A and Parent B, which secures the obligations of the relevant subsidiaries. A Company and its Parent together will be referred to as a Corporate Group.

This briefing is prepared in the context of Corporate Group A but is, of course, generally applicable.

Liability to the Principal

The underlying obligations to the Principal will be set out in the Project Agreement. In most cases, the liability that each of Company A and Company B (the members of the Unincorporated JV) will have to the Principal will be expressed to be on a joint and several basis. That is, the Principal is entitled to seek recovery of the entirety of any claim from either Company A or Company B.

Similarly, under the PCG, each of Parent A and Parent B will guarantee the performance of their subsidiaries under the Project Agreement. The consequence of this is that each of the parent entities will be exposed to the entirety of any claim of the Principal, subject to any applicable liability caps.

The JV Agreement

The JV Agreement will, in most cases include a provision that recognises that liability to the Principal will be on a joint and several basis but provides that liability will be apportioned between the JV members in proportion to the participation interests. Such an agreement is often reinforced by a contractual indemnity given by each party to the other, in respect of any liability incurred by the other in excess of its participating interest. In the absence of any other security, this will only protect the participation interest of Corporate Group A where the claim is made against Company A and Company B is able to financially meet its commitment. It provides no protection to the participation interest of Corporate Group A if the Principal’s claim is made directly on Parent A. In order to provide additional protection, the JV Agreement often includes a provision that recognises that in the event a claim is made against the PCG issued by Parent A, a subsidiary holds on trust for the benefit of its Parent the right to recover from the other JV party, such that the participation interests are maintained. However, this does not perfect the liability gap risk. In particular, it requires:

- Parent A to ensure that Company A is financially viable to enable Company A to pursue its rights under the JV Agreement;

- Company B to be financially viable to the extent required to honour its obligations under the JV Agreement; and

- The trust arrangement must survive any challenge, and this is at risk in a distressed project.

Table 1: Protection provided by standard JV agreement:

| Claim against Company A | Claim against Parent A | |

|---|---|---|

| Protection from Company B | Protection available but only to extent Company B financially viable | No protection without trust provision (and only to extent of trust surviving) |

| Protection from Parent B | No protection | No protection |

Financial Security

Genuine security could be provided by an acceptable form of financial guarantee, a bank guarantee or insurance bond. This is mentioned for completeness. It is expected that in all but the highest risk projects that the costs associated with financial security being required between the parties would be prohibitive. Not considering the need to protect corporate guarantee facilities, the cost would also dramatically increase with each party to the JV, making the tender uncompetitive.

Parent Company Cross Indemnity

A cross indemnity provided by the Parent provides an additional level of security. This arrangement ensures that a claim made against Parent A is contractually covered by Parent B to the extent required to maintain the share of participating interests under the Project Agreement. However, it does not (without additional security) perfect the liability gap risk as it does provide protection from Parent B to Parent A where claims are made against Company A.

Table 2: protection provided by standard JV agreement together with a parent company cross indemnity:

| Claim against Company A | Claim against Parent A | |

|---|---|---|

| Protection from Company B | Protection available but only to extent Company B financially viable | No protection without trust provision (and only to extent of trust surviving) |

| Protection from Parent B | No protection | Protection provided |

JV PCG

A parent company guarantee by Parent B providing a guarantee to Company A could be considered as additional security. However, this may be politically or commercially unacceptable. Many established parent entities are unwilling to be considered as being required to provide security to a junior subsidiary of another company

Table 3: Protection provided by standard JV Agreement together with a PCG:

| Claim against Company A | Claim against Parent A | |

|---|---|---|

| Protection from Company B | Protection available but only to extent Company B financially viable | No protection without trust provision (and only to extent of trust surviving) |

| Protection from Parent B | Protection provided | No protection |

All-Party Cross Indemnity Agreement

The All-Party Cross Indemnity combines the benefit of the JV PCG with the Parent Company Cross Indemnity.

In a single document with all JV parties and their respective Parent Companies, cross indemnities can be established that ensure that claims made against any party can be dealt with appropriately. This ensures the participation interests in the project are contractually maintained.

Where a Corporate Group is offering PCGs to the Principal, it is difficult to consider situations where all-party cross indemnity should not be sought in order to maintain the participating interest and the commercial model.

Table 4: Protection provided by standard JV together with all-party cross indemnity

| Claim against Company A | Claim against Parent A | |

|---|---|---|

| Protection from Company B | Protection available but only to extent Company B financially viable | Protection provided |

| Protection from Parent B | Protection provided | Protection provided |

Exceptions may arise where a Corporate Group is taking a majority interest in a project but considers itself a less attractive “target” for security enforcement. This could be a result of it, for example

- having a lesser financial capacity; or

- being resident in a difficult enforcement jurisdiction,

and the outcome in such case will depend on the relative commercial power of the parties, their interest in the project, and respective risk appetites.

Conclusion

Managing risk and the commercial outcome in projects is a complex and ever-shifting consideration. There are steps that can be put in place that can ensure that bad project outcomes do not have a greater corporate impact.

Michael Debney

Partner, Melbourne

T +61 (0)3 8601 4507

M +61 (0)428 334 084

E michael.debney@hfw.com

Ensuring Arbitration Provides an Alternative Dispute Resolution Process

This briefing explores different tools that can be used in arbitration of construction disputes in Australia, to make it a more efficient and commercial system.

To remain relevant and effective as an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) process, arbitration in the construction industry must provide parties with advantages that are not available in traditional litigation. In Australia, the Courts are efficient and effective, and therefore, litigation remains a process of choice for parties seeking a definitive and enforceable outcome. Having said this, commercial arbitration offers parties with advantages in respect of flexibility (choice of rules, procedures and arbitrators), confidentiality and the support of the Courts (via Commercial Arbitration legislation).

The challenge for arbitration to remain an “alternative” and a choice of an ADR process in the construction industry lies in its cost. Typically, the costs for a construction arbitration are similar and, in some cases, greater than the cost of proceedings in Superior Courts. The scale of the costs of an arbitration may reflect the increased complexity and technical subject matter of a construction dispute, particularly now that “payment disputes” can be resolved through the expedited and, in most cases, cheaper process of adjudication under the relevant State and Territory Security of Payment legislation.

However, the primary causes for the increase in the costs of arbitrations are attributable to several factors, as follows. First, a propensity for parties (in particular their legal teams) to adopt processes that mimic litigation and second, to consider and exploit the flexibility of the processes available to parties when an arbitration clause is being negotiated. All too often, arbitration clauses are negotiated on the “heel of the hunt” and are inserted as a “one-size fits all” solution without sufficient consideration as to the nature of the Project, or the needs and interests of the parties. A carefully drafted arbitration agreement may serve to mitigate those risks. The importance of the drafting and negotiation of an arbitration agreement cannot be overstated.

To reduce the risk of protracted disputes, parties should consider, for instance, the following when formulating their contractual arbitration clauses:

- Segregating claims into a high-value and a low-value group of claims. For example, low-value claims to be determined “on the papers” and the correlating award be final and binding on the parties;

- The inclusion of an agreed position in relation to an appeal process, emergency relief or expedited arbitration process so as to allow a party to seek rapid relief on an interim or final basis; and

- Developing multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses to avoid additional disruption and delay and grounds for jurisdictional challenges.

The most important step is for the parties to invest more time and consideration in the negotiation of these clauses to ensure that they will in fact work (as a matter of process) with their respective project and commercial teams, and that these clauses do not create procrustean results. If domestic arbitration practices model themselves on traditional Court practices, irrespective of who might be the arbitrator, that process is unlikely to provide an improved efficiency or a real alternative to litigation, as originally intended.

Stevana Chaghoury

Associate, Sydney

T +61 (0)2 9320 4618

E stevana.chaghoury@hfw.com

Upcoming Events & Webinars

HFW Webinar

Project Lifecycle: Five Steps to Effective Contract Management

Wednesday 2 March 2022

(1-2pm AWST)

Speakers: Ian Gordon (Partner, Perth); Nick Watts (Partner, Sydney)

HFW Webinar

Tips for Successful Resolution of Disputes Outside Court (Panel Discussion)

Wednesday 9 March 2022

(1-2pm AEDT)

Speakers: Jo Delaney (Partner, Sydney); Nick Longley (Partner, Melbourne); Antony Riordan (Partner, Sydney); Mary Walker OAM (Nine Wentworth Chambers)

HFW Webinar Series: Painting the Future of Arbitration in Asia Pacific

Webinar 3: Effective Case Management

10 March (4-5pm SGT)

Speakers: Nick Longley (Partner, Melbourne); Karen Cheung (Partner, Hong Kong); Chanaka Kumarasinghe (Partner, Singapore)

HFW Webinar

Insolvent Trading: the Protections Provided by Safe Harbour and D&O Insurance Policies

Wednesday 16 March 2022

(1-2pm AEDT)

Speakers: Ranjani Sundar (Partner, Sydney); Sophy Woodward (Special Counsel, Melbourne)

LTC Construction Law Conference

Contract Interpretation

London

24 March 2022

Speaker: Max Wieliczko (Partner, London)

Construction Week Leaders in Construction UAE

Dubai

September 2022

Speakers: James Plant (Partner Dubai/Kuwait), Michael Sergeant (Partner, London)

Construction Week Leaders in Construction KSA

Riy