Global trends in international trade and the laws that underpin them, February 2015

Identifying and analysing the key trends and the legal issues that need to be resolved to support the further development of international trade.

Chapter 1

Introduction

This paper is divided into two parts. The first part considers some of the main global trends that are shaping the current landscape in international trade. Central to this is the rapid economic development of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and MINT (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey) countries. As living standards increase, the demand for raw materials and consumer goods necessitates that the volume of imported and exported goods into and out of the BRICS and MINT countries will increase. Recent experience suggests, however, that the path to full development will be far from straightforward. The paper then goes on to consider some of the challenges to economic growth. The sustained period of economic uncertainty and stagnation amongst developed nations appears to be impeding the growth rates of emerging markets (EM). Nevertheless, the pattern of international trade has been permanently changed by the growth of these countries.

The second part of the paper considers the laws that are relevant to international trade and the way in which these laws have assisted the development of trade, but also what is required to develop them in order to deal with the changing environment in international trade. By virtue of its very nature, international trade requires there to be laws and regulations that will be recognised in multiple jurisdictions. This has given rise to the proliferation of international bodies established in order to promote, govern and regulate certain aspects of international trade on a global basis, such as the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). In addition there needs to be a law that governs the relationships between parties, so that parties engaging in trade can have certainty about the enforcement of their rights and obligations. The challenge of choosing that law and enforcing it is a key challenge for the future growth of international trade as trading patterns change rapidly, an issue which this paper will consider, alongside recent developments aimed at furthering international trade law on a global basis, including bilateral investment treaties (BITs), reciprocal enforcement of judgments and the harmonisation of laws.

Chapter 2

BRICS and MINTS

For much of the past three decades global growth has been driven by the expansion of EMs – in particular the BRICS economies. Since 2000, EMs have accounted for more than half of global GDP growth as the BRICS have routinely recorded double-digit growth figures and by 2013 EM economies accounted for more than half of global GDP on the basis of purchasing power1.

Rapid economic expansion has not been confined to the BRICS, and other EMs have started to emerge as drivers of global growth, including the MINT economies. Indeed, much recent commentary has compared slowing growth in the BRICS with the situation in other EMs. In 2015 Brazil, Russia and China all look set to experience lower growth than in recent years2, even as the expansion of EMs as a whole gathers momentum. Looking to the future, it has been argued that factors ranging from demography to geography will see more rapid growth rates in EMs that do not belong to the BRICS club, in particular the MINTs. For instance, the World Bank has estimated that by 2050 Indonesia’s GDP will be almost seven times its size in 2012, whilst Nigeria’s GDP will be almost nineteen times as big3.

There is no one explanation for the slowing growth in some of the BRICS economies, and to an extent each is confronting a specific combination of issues. In China, a growing debt bubble is causing concern both domestically and internationally, whilst Brazil has been hit by falling commodity prices and a failure to invest in productivity improvements during the boom years. Meanwhile, Russia is set to experience recession after the effects of plummeting oil and gas prices have been exacerbated by the imposition of Western sanctions. Both Russia and Brazil also have serious problems regarding the competitiveness of their private sectors.

However, whilst there is a widespread belief that the era of double-digit BRICS growth is over, their role in the global economy, both present and future, should not be downplayed. For a start, India has recently upgraded its GDP growth forecast for the 2014 financial year from 4.7% to 6.9%4. Moreover, despite the weaknesses of particular BRICS, the size of their combined economies is set to exceed that of the US economy by the end of 20155. Over the next three to four years each of the BRICS predicts continued economic growth, with India expecting year-on-year growth to rise to between 7% and 8% between 2016 and 20186. Despite the significant problems many foresee for the BRICS economies, others have been encouraged by the willingness of the administrations in the two most populous – China and India – to confront these issues with practical and effective policy decisions. This growth is still very significant when compared with the old world economies.

The BRICS grouping is also becoming increasingly assertive on the international financial scene. In July 2014 they founded the New Development Bank, or ‘BRICS Bank’, which has been seen as a potential challenge to the hegemony of the US-led post-Bretton Woods global financial and monetary system. Other evidence points to a growing perception that the continued growth of the BRICS and other EMs will continue to alter radically the structure of the global economy.

Even if the pace of EM growth does not return to the levels reached in the previous decade, it is inevitable that the size and importance of EM economies will grow, as will the assertiveness and confidence of the governments overseeing these economies. International trade will be a significant part of this growth. Even as China looks to stimulate domestic demand and to reduce its reliance on exporting goods, it will remain an important international trade player. Meanwhile, India’s recently-elected government, is looking to stimulate its trade with major international partners from the USA7 to Japan8 whilst Turkey has identified diversifying its exports as a major economic objective9. Exports are also a key driver of Mexican economic performance, and should continue to expand if economic growth in the United States is sustained and if the Mexican government persists with its economic and political reform agenda.

In the coming years, the growth of trade between EMs will far outstrip the increase in trade between advanced economies, radically re-shaping international trade routes. The type of goods being traded will also transform as EMs move away from a reliance upon exporting basic commodities and start to produce more refined goods, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, amongst other things. Between now and 2030, huge growth will be seen in trade linkages between regions which bypass the developed economies of North America and Europe – in particular trade between South America and the Asia-Pacific region10. Clearly, the coming years will, if anything, see an acceleration of the rise of EMs and their role in the global economy.

Chapter 3

Key drivers of growth

Future drivers of economic expansion will be diverse and will differ between economies, as each derives growth from a variety of sources. Below are examples of the predicted future trends in three of the largest regions in international trade, namely China, the Unites States of America and the European Union.

China

Chinese economic policy will continue to focus on boosting domestic demand and consumption, as policymakers look to enact a shift away from reliance on export-led growth. As the Chinese economy develops and affluence increases, consumption patterns will progressively resemble those of developed economies. The rise in year-on-year retail sales has been steady over recent years, with growth becoming increasingly strong in the market for higher-end goods and food as consumption patterns adapt to the population’s increasing wealth11.

The Chinese government estimates that investment in fixed assets is particularly important to keeping growth rates stable12. Investment levels are dipping (notably in the manufacturing and construction sectors), which is seen as a significant cause of the recent economic slowdown13. Despite stimulus measures (including an interest rate cut) imports in January 2015 were down 20% when compared with the same period in 201414. Imports of crude oil and coal also saw marked falls at the beginning of 201515. Such trends have wider regional and global effects, particularly as they are factors in pushing down global commodities prices. This will be discussed in the next chapter.

However, in the long-term, Chinese growth will remain high by global standards. There are reasons to see the recent slowdown as a blip, even if it does signal the start of a less intense period of growth (in percentage terms) than over the last few decades. The average annual growth rate in China over the last 30 years exceeded 10%16, and even if rates remain at the current rate of 7% to 8% that, on any view, will amount to very significant growth over the coming years.

However, in the long-term, Chinese growth will remain high by global standards. There are reasons to see the recent slowdown as a blip, even if it does signal the start of a less intense period of growth (in percentage terms) than over the last few decades. The average annual growth rate in China over the last 30 years exceeded 10%16, and even if rates remain at the current rate of 7% to 8% that, on any view, will amount to very significant growth over the coming years.

Further encouragement can be derived from the re-balancing of the economy. In the past there were fears that the economy was over-reliant on (often inefficient) investment and that consumption was too weak. By contrast, recently the relative proportions of investment and consumption appear to have found a more sustainable equilibrium. The investment-to-GDP ratio has dropped, whilst consumption accounts for a steadily rising proportion of growth18. Employment and wages are also rising, which will further boost consumer activity19.

GDP growth rates will be between 7% and 8% in 2015 and 2016, far outstripping the OECD average20. According to a survey by PwC, between 2011 and 2050 Chinese GDP, both in terms of purchasing power parity and per capita, will grow at an average rate of over 4% per annum – becoming the world’s largest economy21. Of the countries surveyed, only Nigeria, Vietnam, Indonesia, India and Malaysia would enjoy faster-paced growth22.

Continued economic growth, added to population expansion, will see imports rise significantly in the medium- to long-term. It is predicted that China’s expanding and wealthier population will drive imports of an increasing range and quantity of foodstuffs, as well as high-specification transport-related and industrial goods23. Exports will also continue to grow (at an annual average of 10% to 2030), especially those to EMs in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. A rising proportion will be IT and industrial goods, although sectors like clothing will remain strong24.

USA

In contrast to most developed economies, the USA has recently enjoyed rapid growth which is expected to last into the foreseeable future. Job creation is healthy and falling prices are boosting consumption. Investment is also high. In the next few years the US government expects economic growth to remain strong, inflation to remain steady and low, and unemployment to continue to fall25.

Whilst weakness in the eurozone and several commodity-exporting EMs could slow this growth and dampen exports, growing domestic demand and a strong dollar should encourage imports. Whilst a strong dollar could have an adverse impact on large multinationals with significant non-US revenue streams, on the whole the outlook is positive for both consumers and the majority of American companies. Cheaper oil, cheaper imported goods and continued low inflation all herald optimism for an economy that is powered by consumer spending26. The long-term outlook is good – and whilst it appears that China will shortly overtake the USA to become the world’s largest economy, American GDP is still expected to expand consistently and to roughly double in size by 2050, growing to US$30-40 trillion27.

Europe and Beyond

The eurozone’s troubles continue and recent political events have prompted fears that the currency bloc could see a return to the turbulence experienced at the height of the crisis in 2010-2012. Economic weakness in Europe has a clear knock-on effect in EMs, in that weak demand hurts exports in economies from Turkey to the Far East28.

However, the long-term predictions still forecast steady GDP growth in the main developed European economies (principally the UK, France and Germany)29. Even in the short term, the EU and European Central Bank have revised up their forecasts for 2015 and 2016 and for the first time in 8 years all EU Member States are expected to record positive growth figures30. Eurozone GDP figures for the last quarter of 2014 also beat expectations – in several countries investment was strong, the low oil price boosted domestic consumption and the weak euro prompted increased exports31. As long as the euro remains weak, trade will remain a central plank of several governments’ growth strategy – Italy, for example, is relying on growing exports to leave recession32.

In addition, economic confidence in several central and eastern European countries – primarily Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic – is high33, notwithstanding geopolitical uncertainty caused by European tensions with Russia. Even if European performance does disappoint, this should be off-set by continued EM economic growth which, as has been seen, looks positive in the medium and long-term. In particular, Indian economic performance is exceeding expectations and across EMs several key indicators – including the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) – show that there is a good deal of confidence in future economic performance34.

Chapter 4

Obstacles and challenges to growth

Whilst there may be several reasons for optimism in the medium and long-term, the general outlook for global growth in the short-term appears to be more pessimistic. This is most likely due to a combination of factors which together are causing instability and a lack of confidence in the recovery from the global financial crisis.

Perhaps the greatest cause for concern in the context of international trade is the apparent slowdown in the growth rate of the Chinese economy, which last year expanded at its slowest rate in over twenty years. Although the latest official figures indicate that the growth rate has stabilised at 7.3% per annum, there are other indicators that suggest that the position is less secure. Of particular relevance to international trade, a recent survey published by the Customs Administration indicates that in January 2015 the Chinese monthly trade surplus grew to a record US $60 billion. Against the figures for the same period in 2014, imports fell by 3.3.% and exports by 19.9%. Both these figures were worse than expected by analysts. It is reported that the main reason behind the reduction in exports was the slow down in the manufacturing sector, which contracted for the first time in two years.

These figures have two main knock-on effects for international trade. First, as the largest manufacturing nation in the world, China’s figures are often seen not in isolation but as an indicator of the general health of the world economy. Therefore, if Chinese manufacturing and exports are declining, there is a presumption made that global demand for manufactured goods is also declining. This in turn may indicate that the health of the global economy is less strong than previously thought. Secondly, if Chinese imports are falling, China is buying a reduced number of goods from other countries, with the consequence that the exports of the rest of the world will be reduced and their growth rates similarly affected. Against this backdrop, investors are often deterred from capital spending in international trade, an issue which can exacerbate the problem further.

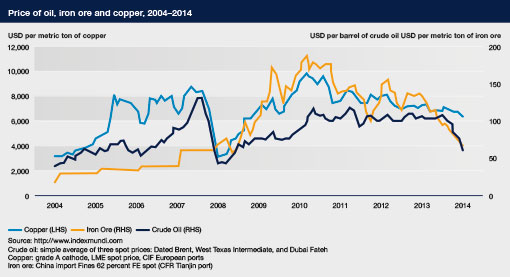

In commodities, reduced Chinese demand has contributed significantly to a drop in overall global demand. This fall in demand has coincided with a supply glut leading to a rapid slump in oil, iron ore and copper prices (see table on page 8) which the National Resource Governance Institute described as “probably the most dramatic aspect of the early 2015 global economy.”35 By way of example, in June 2014 Brent crude oil was trading at US$115 per barrel. At the time of writing (February 2015), the price of Brent is approximately US$55 per barrel (in mid-January 2015 it fell as low as US$45 per barrel). Since February 2011, copper prices have fallen 38% and iron ore 63%.36

This over-supply has been caused in large part by a refusal of the major producers to reduce their production levels in response to the fall in demand. For example, following their annual meeting in Vienna in November 2014, OPEC announced that it would not cut crude oil production, despite the price crash described above. It is widely reported that the basis for this decision was that the largest and most influential member of OPEC, Saudi Arabia, did not want to risk sacrificing its market share in light of the boom in shale oil production. Similarly, four of the largest iron ore producers, BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Anglo-American and Fortescue Metals, have openly pursued a strategy of flooding the market with tonnage to drive the price down with the reported intention of forcing less efficient producers out of the market, thereby eventually leading to a reduction in supply. The strategy is not without risk as a large number of the less efficient producers targeted by the “big-four” are either state or state-backed entities, and are therefore not as vulnerable to market fundamentals as private companies. Whether this emphasis on taking short-term pain to maintain market share will be successful or indeed sustainable remains to be seen. However, the consequences will be far reaching in terms of how commodities markets respond to over-supply in the future.

In the more immediate term, the sudden and marked fall in commodities prices is having a significant impact on the global economy. Whilst countries that are net consumers of commodities are welcoming the reduced costs, producing nations (for example many of the African and South American nations) that are heavily reliant on the income generated by commodities are faced with the prospect of significant budget deficits. It is conceivable that this may in turn lead to increased borrowing, higher taxes and, in the worst case scenario, political instability. In regard to market participants in commodities, such as the oil majors and large traders, the response to date has been to cut capital spending and bring forward divestment from unprofitable assets. It may also be necessary for producers to consider new ways of raising finance, such as through private equity, pre-payment off-take agreements or the issuing of convertible bonds.

A further cause for concern in the development of international trade is the significant ongoing geopolitical tensions in Ukraine/Russia and Syria, Iran and Iraq. International trade relies on the free movement of goods and services in and out of different jurisdictions. Geopolitical tensions therefore impede international trade both in a practical sense, as political turmoil and violence severely limit the physical movement of goods, and in a legal sense, as sanctions put in place by the European Union and the United States of America in particular, have restricted the types of trade permitted with these nations. In the case of Russia, the sanctions have been met in kind with the imposition of restrictions on the import of certain food types from western countries. Again, it remains to be seen what the long-term impact will be on international trade as a result of these conflicts.

Political instability within a country is also a recent factor impacting on international trade. Piracy has been a recent problem off the east coast of Africa, and has recently re-emerged off the coast of west Africa. Whilst the international community has worked together to resolve the issues in east Africa (with the use of convoys, navy patrols, and armed guards), this was an issue which significantly impacted international trade at the time.

Chapter 5

Trade routes

The shipping industry, one of the central components in international trade has been subject to significant turbulence since the global financial crisis. Freight rates have plummeted as global demand for commodities, especially in China, has fallen. In February 2015, rates on the Baltic Dry Index reached their lowest ever level37. The rates for bulk commodity carrying ships could remain at these historically low levels if Chinese steel output and coal demand remains low. Most analysts do not predict an upturn in rates in the immediate future, with the most optimistic predictions not foreseeing a rebound until the second half of 201538.

A major cause of the drop in rates has been over-capacity on many shipping lines, exacerbated by the slowing of trade growth since its 2008 peak. Some have said that freight rates could even decline in the next few years as year-on-year trade growth is unlikely to attain its pre-2008 levels in the foreseeable future39.

Beyond this near-term view, in the longer term patterns of global trade are likely to alter radically. As demand remains weak in advanced economies but continues to expand in EMs, the volume of intra-EM trade will constitute an increasingly important proportion of total global trade flows40. Currently under-utilised trade routes will grow in prominence – for example, that between Argentina and India41. China’s dominance of international trade will grow, and by 2030 it will feature in 17 of the top 25 bilateral sea and air freight routes42. Between 2009 and 2030 the countries featuring in this ‘top 25’ will change noticeably, and several countries not featuring at all in 2009 will be listed by 2030 (including Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, India and the UAE)43.

Despite these drastic shifts, several established trade routes will remain amongst the most-used in global trade. For the foreseeable future, China will remain Brazil’s main export destination, whilst Canada, Mexico and China will remain the USA’s biggest export partners44. Other established bilateral trading relationships which will remain amongst the world’s largest include those between Japan and China and Japan and the USA, as well as the USA’s strong trade relationships with European countries like Germany and the UK45.

Added to this, new shipping routes could also impact upon international trade flow – in particular, the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which follows Russia’s northern Arctic coastline. As Arctic sea ice melts, it is becoming increasingly possible for large vessels to sail in ever quicker times from Europe to Asia. Via the NSR, the sailing time from Rotterdam to Kobe or Busan could be reduced by almost a third when compared with the traditional route travelling through the Suez Canal46. The tonnage sailing via the NSR is growing rapidly – in 2010, just 4 vessels made the voyage. By 2012 this had increased to 46, and in 2013 the number of transit permits issued by the Russian authorities was 8 times this number47. South Korea’s Maritime Institute estimates that the NSR could account for 25% of all trade between Asia and Europe by 203048. A combination of factors, from accelerating climate change to heightened geopolitical tension in the South China Sea to piracy could see the NSR become an increasingly viable and popular choice for vessels carrying goods between Asia and Europe.

There has even been a suggestion that melting ice could open up the Northwest Passage (passing over Canada and Alaska) to more large commercial vessels, which could also save tens of thousands of dollars in fuel costs49. Even though this is widely seen as having less commercial potential than the NSR, it is a further illustration of how factors ranging from climate change to economic development will rapidly alter global trading patterns in the future.

Chapter 6

e-Commerce

The growth of e-commerce is a further factor that will drive the development of international trade patterns and relationships over the coming years. Over the last two decades, the huge growth of e-commerce platforms like eBay and Amazon has changed the way many consumers access domestic and international markets for a range of goods. This trend looks set to continue as new companies, especially in emerging markets (notably, Alibaba) continue to grow and expand. The nature of e-commerce itself will also transform, especially with the growth of commerce conducted on mobile phones and other portable devices (so called “m-commerce”).

The Chinese e-commerce market is forecast to undergo substantial growth in the next few years, growing from less than 500 billion yuan in 2012 and 2013 to a figure in excess of 3 trillion yuan by 201750. As the rates of internet access amongst EM consumers continues to improve, the possibilities for e-commerce will escalate. One study found that between 2013 and 2014 the number of Indian respondents who had used the internet for shopping in the past year had increased from 20% to 32%, and between 2010 and 2014 the number of people with internet access in India more than doubled, a trend also visible in other EM countries such as Indonesia51. Several African markets, including Nigeria and Kenya, also have well-developed e-commerce markets.

In addition to transforming national and domestic retail markets, e-commerce could have an equally profound impact on international trade. Several e-commerce platforms, from eBay to the Japanese firm Rakuten, have expanded their activities into multiple new markets. The Chinese e-commerce behemoth Alibaba has also expressed a desire to expand its global operations beyond its domestic market52.

The potential of e-commerce extends beyond the consumer retail sector. As will be discussed in section 9 of this paper, for decades there has been an increasing ‘electronic’ role in international trade – especially with the development of instant communication technology – and courts have had to develop appropriate legal responses to the important developments in international trade which technological advance has caused.

In addition to electronic communications, electronic trading documents have also had an impact on the way that trade is conducted, and continued innovations ensure that this will also be the case in the future. One such innovation is the introduction of electronic Bills of Lading. Using soft or electronic copies of trade and commercial documents as opposed to hard copy versions has a multitude of potential advantages. As well as reduced waste and delay, e-documents can diminish the risk of fraudulent documents being created and, by virtue of being accessible by multiple parties in their ‘original’ format, allow for the increased integration of systems and document storage along the whole supply chain. In the past, the increase in use of electronic Bills of Lading has been slow, as every party in the contractual chain must be a party to the same trading system. However, if applied to all documents routinely used in commerce – from trade finance documents to invoices to certificates of origin – the impact could be significant and could greatly improve efficiency at several stages of the typical international trade transaction.

As technology improves and as ever more people around the world have access to the internet and the online commercial marketplace, the role of e-commerce will inevitable grow in size and importance. It appears that, increasingly, large commercial transactions will be conducted on an almost exclusively e-commerce basis, for instance from the negotiation and agreement of contracts by email to the conclusion of the transaction and the delivery of the goods under the agreement by the presentation of an electronic Bill of Lading. In this context, it will be increasingly important to develop international frameworks which facilitate the conduct of international trade, whether this is by means of designing integrated online trading platforms or by putting in place international agreements to regulate and govern the conduct of international trade by means of e-commerce. This will be further considered in the next chapter, which will consider the role of international agreements and conventions in the regulation of international trade and commerce.

Chapter 7

Nature of international trade

In the mediaeval and early modern eras, the growth of international trade – or trade between the citizens of separate political entities – in Europe and the Middle East, gave rise to an increasing volume of disputes in which the ‘conflict of laws’ became an issue. Courts were increasingly required to decide upon cases which contained a large foreign element53. Such disputes gave, and continue to give, rise to three key questions where the court of one state is called upon

Download a PDF version of ‘Global trends in international trade and the laws that underpin them, February 2015’

-1024x683.jpg)