HFW Client Defeats Claim of Seaman Status Using New Sanchez Factors

In Sanchez v. Smart Fabricators of Texas, LLC, 997 F.3d 564 (5th Cir. 2021), the en banc U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals clarified the judicial test for seaman status under the Jones Act.

Since the May 11, 2021, opinion, only a handful of district courts have analyzed its holding. Recently, a federal district court in the Southern District of Texas denied remand after finding a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) supervisor, employed by an offshore contractor, was not a seaman according to the new Sanchez factors. The court’s ruling will provide further clarity to those employers challenging Jones Act seaman status in the offshore energy industry.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s test for seaman status

In Chandris v. Latsis, 515 U.S. 347 (1995), the Supreme Court established a two-prong test to determine whether a person is a seaman1 under the Jones Act.

- The person’s duties must contribute to the function or mission of a vessel.

- The person must have a connection to a vessel or fleet of vessels that is substantial in terms of both (a) duration and (b) nature.

The Fifth Circuit’s Sanchez course correction

HFW previously reported2 on the Fifth Circuit’s en banc decision in Sanchez urging the following inquiries in order to distinguish seamen and non-seamen who may face similar risks and perils of the sea:

- Does the worker owe his allegiance to the vessel, rather than simply to a shoreside employer?

- Is the work sea-based or does it involve seagoing activity?

- (a) Is the worker’s assignment to a vessel limited to performance of a discrete task after which the worker’s connection to the vessel ends; or (b) does the worker’s assignment include sailing with the vessel from port to port or location to location?

The contractor’s ROV supervisor

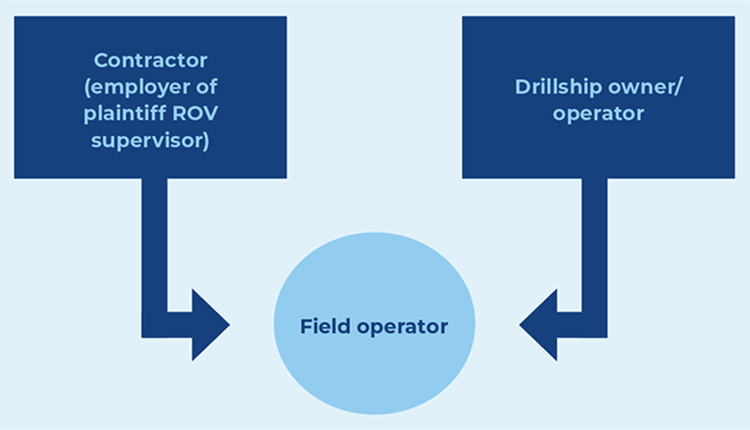

The contractor employed the plaintiff ROV supervisor for decades during which he performed services on various vessels owned by numerous entities. For the five years prior to his alleged personal injury, however, he worked primarily aboard one drillship in the Gulf of Mexico providing ROV services for the field operator. After the field operator removed the plaintiff’s state court Jones Act lawsuit to federal court based on federal question jurisdiction arising under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, plaintiff filed a motion to remand. The contractor responded that the plaintiff’s Jones Act claims were fraudulently pleaded because he was not a seaman. When examining whether the plaintiff’s connection to the vessel was substantial in nature, the federal court analyzed each of the Sanchez factors.

Did the plaintiff owe his allegiance to the vessel, rather than simply to the contractor, his shoreside employer?

The court found that the contractor employed the plaintiff, rather than the vessel’s owner or the field operator. The ROV technicians aboard the vessel were separate from the vessel and drilling crews and followed a separate chain of command. Further, despite primarily working aboard the drillship during the five-year period, he occasionally performed ROV services from different vessels for different operators. As a result, he did not owe his allegiance to the vessel, but rather to the contractor, his shoreside employer.

Was the plaintiff’s work sea-based or did it involve seagoing activity?

In short, yes it was sea-based. The plaintiff spent a significant amount of time at sea on various contracts. This factor alone, however, was not sufficient to meet the nature requirement.

Was the plaintiff permanently assigned to the vessel?

In answering no, the court pointed to the plaintiff’s decades-long work history with the contractor “showing he was never permanently assigned to a vessel or a fleet of vessels, but rather temporarily assigned to perform discrete services.” In addition, although he worked aboard the drillship during most of his last five years, at times he temporarily transferred to other vessels working under other contracts. “While [the plaintiff] did spend a longer time on the [drillship] than other contractors between 2016 and 2021, this was due to the nature of the ROV services he and [the contractor] provide[d] and not because he was permanently assigned to the [drillship]. [The plaintiff’s] presence on the [drillship] was dependent on the contract for discrete services between [the contractor] and [the field operator]. Therefore, the Court finds [the plaintiff] was not permanently assigned to the [drillship], or a fleet of vessels to which [the drillship] belongs.”

What have we learned from this opinion?

- A plaintiff’s sole reliance on his allegation of seaman status is not enough to win a motion to remand where his employer puts on admissible evidence otherwise.

- Sea-based work alone is not enough to prove connection to a vessel substantial in nature.

- A discrete task does not necessarily mean a short-term assignment. Five years is a long time, but because the assignment was based on a contract between the contractor and the field operator, it was for a finite period.

Footnotes:

- The federal statute which gives rise to a claim for Jones Act negligence refers to injury to a “seaman,” 46 U.S.C. § 30104, without regard to the fact that seafarers include both men and women. This newsletter tracks that terminology because the plaintiff at issue is male. One day, however, these authors hope to see more gender-inclusive language incorporated into federal statutes, including the Jones Act.

- https://www.hfw.com/Sanchez-v-Smart-Fabricators-Course-Correction-for-the-Seaman-Status-Test

Download a PDF version of ‘HFW Client Defeats Claim of Seaman Status Using New Sanchez Factors’