Aerospace

Pre-eminent specialist aviation lawyers offering global experience combined with regional insight and deep-rooted sector knowledge.

Commodities

Providing legal expertise and support for all hard and soft commodity related matters.

Construction

Specialist construction team working internationally on some of the largest and most technically complex projects across procurement, risk management and disputes.

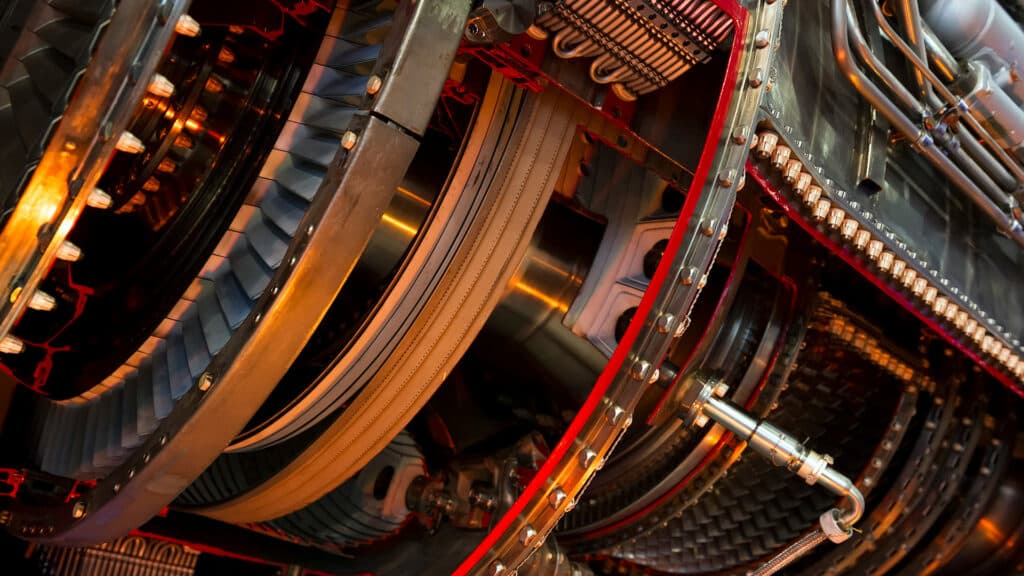

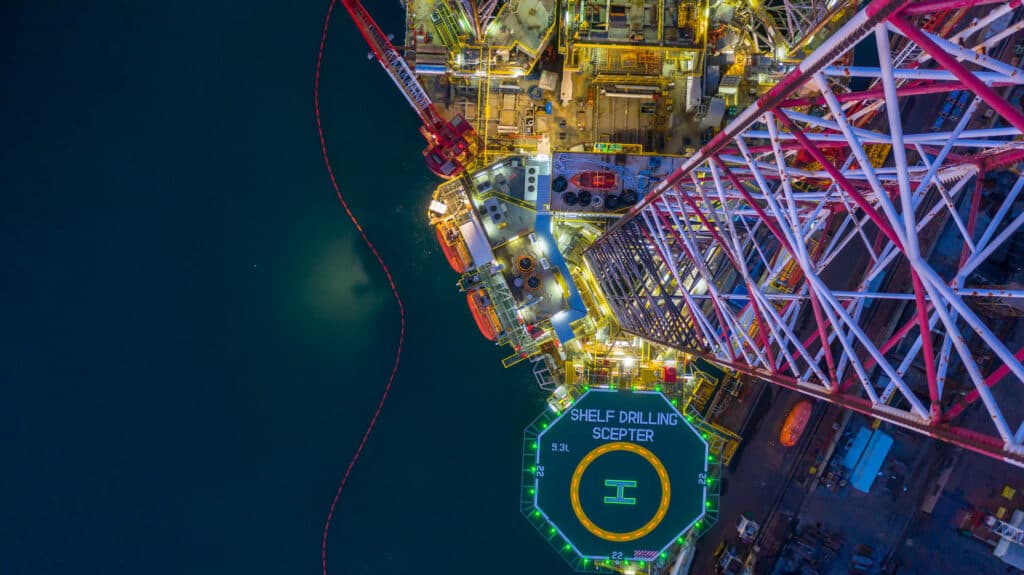

Energy

True industry specialists working collaboratively across borders to provide creative solutions throughout the energy chain.

Insurance & Reinsurance

Specialist multi-jurisdictional lawyers providing first-class advisory and dispute resolution legal services to the insurance sector.

Shipping

Widely recognised as the world’s leading shipping and maritime law firm, serving clients in the industry for over 140 years.