Bulletins

Hong Kong Aerospace Bulletin, September 2019

In this bulletin, the latest in our current series of Hong Kong-related aviation bulletins, we look at both recent and forthcoming aviation developments in the region with a focus on finance-related issues, exploring the implications behind the acronyms of LIBOR, JOLCOs and IDERAs.

LIBOR – A growing concern

LIBOR was the world’s pre-eminent benchmark interest rate for players entering into floating rate debt arrangements. Now financial markets and regulators are scrambling to transition to “risk-free rates” before LIBOR’s likely discontinuation in 2021.

The following article provides a look into the risks faced by lenders and borrowers who are currently using LIBOR in documentation, the future after LIBOR and some practical tips for stakeholders to mitigate some of the risks and uncertainties caused by LIBOR’s discontinuation.

A short history of LIBOR

The London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) provides a number of benchmark interest rates for five currencies over seven maturities, which are used as a base rate for pricing debt finance products and has been referred to as the world’s most important number.

To illustrate the widespread usage of LIBOR, management consultancy Oliver Wyman estimates that more than US$240 trillion in debt finance products reference LIBOR. 1

LIBOR was first published in 1986 but, in 2012, ran into issues. It became apparent that some of the banks providing the reference rates that are used to calculate LIBOR were reporting artificially high or low rates, in order to achieve specific profit margins for those banks in certain transactions.

As a result of what became known as the LIBOR rigging scandal, US and UK regulators levied more than US$9 billion in fines on the banks involved and criminal charges were brought against culpable individuals.

The Finance Conduct Authority of the UK (FCA) also removed responsibility for the administration of LIBOR from the British Bankers Association and installed the ICE Benchmark Administration as the guardian of LIBOR going forwards.

The FCA, however, announced that it would only expect LIBOR to continue to be published until 2021, from when new “risk-free rates” (rates that have been described as “embedding no or only small amounts of risk” by the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC)) should replace LIBOR in documentation.

In mid-July 2019, Andrew Bailey, Chief Executive of the FCA, warned that LIBOR may be subject to a very sudden discontinuation in 2021 because “there is a high probability [it] will no longer pass regulatory tests of representativeness”. 2

What are the implications of LIBOR for lenders and borrowers?

Any floating rate debt arrangements entered into before 2021 are likely to rely on LIBOR as the basis for the interest rate payable under those debt arrangements. Contracts will usually have “fallback” provisions if LIBOR is not published for a period in respect of which interest is payable.

However, the danger with using fallback provisions is the onset of high operational demands and risks resulting from the need to calculate, process and, in some cases mitigate, the fallback formula used, interest payments and asset valuations to be made and collateral requirements.

For lenders in particular, this risk could be for such a high number of contracts that doing so will be time consuming and unachievable in the context of the timing of payments under all of its applicable contracts.

Borrowers risk finding themselves in a very different financial position to that which they calculated when entering into their LIBOR-based transaction.

A more specific concern is whether those fallback measures will be applicable. Some such measures rely on “reference rates” given by “reference banks”.

If those banks are no longer providing reference rates for the purposes of LIBOR, it is possible that they will not provide a rate for the purposes of a fallback provision.

If reference bank rates are the only fallback provision, this will leave uncertainty as to how the applicable interest rate should be calculated. In other scenarios, it might be unclear which fallback provisions should be followed, potentially leading to disputes and litigation over amounts payable.

Where borrowers find that the fallback provisions relating to their debt financing are not favourable, those borrowers might seek to find the discontinuation of LIBOR as a reason to terminate a contract.

The Chief Executive of the FCA has previously commented that “fall backs are not designed as, and should not be relied upon, as the primary mechanism for transition. The wise driver steers a course to avoid a crash rather than relying on a seatbelt”. 3 All parties should bear this in mind with LIBOR-based contractual arrangements, in the context of their own intentions and expectations.

Additionally, there are potential regulatory risks for lenders entering into LIBOR-linked contracts between now and 2021.

Dave Ramsden, Deputy Governor for Markets & Banking at the Bank of England, advised that, for LIBOR-based documentation, “the time for ‘last orders’ is now. Firms need to…stop adding to their post 2021 LIBOR exposures…firms need to educate their customers”. 4 Lenders need to be aware of potential claims if they fail to explain to customers that LIBOR will be discontinued or fail to provide appropriate fallback provisions.

Post-LIBOR: The future

In early April 2018, the New York Federal Reserve began publishing the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), a risk-free rate that is intended, in the long run, to replace LIBOR as the basis of US$-backed debt financings.

The ARRC has selected SOFR as an alternative to LIBOR for the purpose of derivatives transactions. SOFR is based on transactions in the US Treasury repurchase market, in which Treasuries are borrowed or loaned on an overnight basis.

Despite the development of SOFR, challenges remain in transitioning from it to LIBOR. Contracts do not contain specific provisions facilitating a change in the base rate and parties will need to agree appropriate documentary amendments to reflect the change.

From a practical perspective, however, parties will need to bear in mind that one rate is not replaceable by another without an impact on pricing.

As LIBOR is based on unsecured interbank lending, it prices debt transactions in a different way from SOFR, which is based on overnight lending back by treasury bonds.

More theoretical questions have arisen over concepts such as break costs, protection for lenders over change in law, increased costs and illegality and yield protection, which will each need to be dealt with on a case by case basis.

How should stakeholders mitigate uncertainty now? Practical tips

Given that 2021 is rapidly approaching and transition processes are, generally, considered to be slow, what should stakeholders do now to mitigate the risks of waiting until nearer to the drop-dead date for LIBOR?

We suggest:

- Considering your preferred approach post-LIBOR given your relevant LIBOR-related documentary provisions and your expectation to achieve that position

- Engaging with all your counterparties with a view to agreeing an approach in good time to ensure a smooth and timely transition

- To the extent possible, beginning a quantitative analysis of any proposed approach and stress testing it to ensure the expected outcomes can be achieved.

We have a wealth of experience and knowledge to assist. with your transition planning and risk management in the lead up to the discontinuation of LIBOR, transition to and documentation of SOFR or other appropriate risk-free rate, and post-LIBOR challenges.

Footnotes

- Oliver Wyman "Time to Switch Rates LIBOR Transition" June 2019 Edition.

- Speech by Andrew Bailey on 15 July 2019 at the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association's (SIFMA) LIBOR Transition Briefing in New York, USA.

- Speech by Andrew Bailey on 12 July 2018 at Bloomberg, London - on transitioning from LIBOR to alternative interest rate benchmarks.

- Bank of England event “Last orders: Calling time on LIBOR” on 19 June 2019.

JOLCOs

Traditionally a product geared towards lower costs for airlines and tax benefits for Japanese SME investors, Japanese operating leases with call options (JOLCOs) have become an established financing structure for the aviation market seeking flexibility in financing and equity investor-reward.

We at HFW have been advising clients on JOLCOs in the aviation sector for several years, and, more recently, in the shipping industry. We outline a typical JOLCO structure, their benefits and challenges below.We at HFW have been advising clients on JOLCOs in the aviation sector for several years, and, more recently, in the shipping industry. We outline a typical JOLCO structure, their benefits and challenges below.

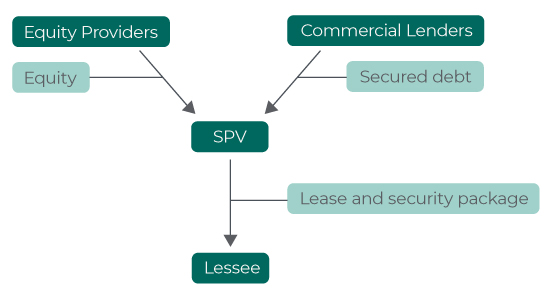

Typical JOLCO structure

JOLCOs are tax-based leasing products that take advantage of Japanese tax laws to attract equity from Japanese tax-paying investors and combine that equity with commercial loan finance to provide up to 100% financing for the lessee.

In essence, a JOLCO is a typical operating lease with a call option (i.e. option to purchase the asset) that may be exercised by the lessee at one or more fixed points during the lease term. The JOLCO almost invariably forms part of a sale and leaseback transaction under which the lessee sells the asset to the lessor and leases it back under the JOLCO.

In terms of usual structure, a Japanese special purpose vehicle (SPV) will be incorporated by a Japanese equity arranger. Equity in the SPV will be contributed by Japanese investors (often small and medium sized enterprises).

The SPV will enter into loan arrangements with commercial lenders, who will provide debt funding for a proportion of the asset purchase price (usually around 70%) to the SPV. The SPV will apply the equity contributions and the debt to purchase the asset.

Simultaneous with the asset purchase, the SPV will enter into an operating lease with the lessee (an airline or shipping company), which will include the call option.

Pricing for the operating lease is structured such that the lessee will incur far higher costs (increasing rental payment and more restrictive return conditions) if it does not exercise the purchase option on the specified date in the lease (or arrange for another financing, which will involve the purchase of the asset from the SPV).

It is important to retain separation between the distinct parties at each layer of the transaction, i.e. the lessee, the SPV, the lenders and the equity providers.

As such, security is provided by the lessee to the SPV, which will on-assign that security to the commercial lenders in addition to securities the SPV provides itself, which will include a mortgage over the asset in all appropriate jurisdictions depending on the jurisdiction of registration of that asset and the relevant security framework. The banks have limited recourse against the Japanese SPV, and the lessee limits its exposure to the SPV and the banks.

The equity arranger will provide little, if any support in respect of the SPV, usually limited to a support letter in favour of the lenders and another in favour of the lessee.

Why are JOLCOs such an attractive structure?

Each participant can benefit from the transaction’s distinct structure and nature.

Lessees

Commercial lenders are unable and unwilling to provide debt finance in respect of 100% of the price of an asset, owing to capital adequacy requirements and ongoing changes in accounting principles.

As such, lenders will usually only provide up to 70% of the value of an asset.

The JOLCO structure, however, enables this 70% debt finance to be combined with 30% input by the Japanese investors, negating any need for financial outlay by the lessee, other than in respect of rent.

Lessees also gain the benefit of lower rental rates; the Japanese tax position is that lease returns cannot exceed 90% of the asset’s purchase price, plus associated acquisition costs (such as interest payable to the lenders).

Aligned with this is the lessee’s limited exposure to the lenders and equity providers under the JOLCO structure. The lessee benefits from the gains whilst not encumbering itself with any additional exposure.

Lessors

The call option provides the equity investor with an orderly exit from the leasing arrangements without having to enter into remarketing arrangements at the lease’s expiry.

If, on the other hand, the lessee elects not to exercise the call option on the relevant date, the equity investors are rewarded with an uplift in rent as compensation for having to carry on through to the lease expiry date.

Alternatively, if the asset is sold during the lease term for an amount greater than its residual value, the investors will receive the remainder of the purchase price following the repayment of the lenders.

Equity investors

Japanese tax treatment of the investments made by the Japanese equity investors benefits the investors in their ability to apply a double declining balance sheet depreciation method to their accounts.

The resulting enhanced losses incurred by each investor – as a result of the depreciation in value of the asset and costs of funding the JOLCO structure – lead to tax allowances for that investor, which can be offset against taxes incurred by its profitable affiliated businesses.

This has made the JOLCO structure particularly attractive to small and medium-sized enterprises and high net worth individuals looking to defer their aggregate tax exposure.

Lenders

The lenders have greater confidence in lending, based on the strength of the lessee’s credit rating. Whereas lenders might not be able or inclined to lend directly to airlines or shipping companies, notwithstanding their strong credit profile, the JOLCO structure permits indirect lending with the benefit of the strength of that credit being passed through the SPV.

Developments in JOLCO use in the aviation sector

Historically, narrow-body aircraft were the preferred asset for JOLCO transactions, given the lower equity investment required compared with wide-body aircraft; typically investors preferred aircraft such as the A320 and B737 models.

With increased confidence and usage in JOLCOs, we are, more recently, seeing the structure used to finance wide-body aircraft, such as the A330, A350 and B787 models.

Again historically, only “industry giants” or tier-1 airlines that flew to Japan were considered JOLCO-appropriate participants, due to their strong credit profile and asset pool depth. Smaller airlines were seen as unable to provide a strong enough package to tempt investors.

Over time, however, new market entrants have emerged, and now a wide range of airlines – including low-cost, no frills carriers – are participating, thereby demonstrating the wide-ranging appeal of JOLCOs.

Furthermore, no Japanese nexus is required, meaning any airline can engage in JOLCOs, regardless of its operational locations.

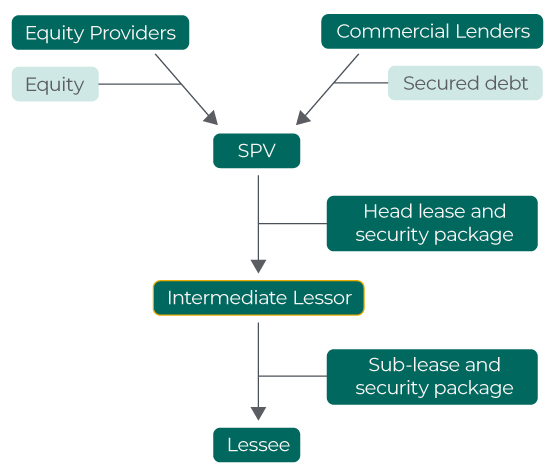

The last few years have seen a change in JOLCO structures, with the introduction of an intermediate lessor, resulting in the transaction structure shown above.

In such a transaction, the SPV leases the aircraft to the intermediate lessor, who sub-leases the aircraft to the sub-lessee. This type of structure provides a second layer of comfort to lenders and equity providers through the credit of both the intermediate lessor (which in most cases has a strong credit profile itself) and the lessee, and an enhanced security package provided by the intermediate lessor.

The sub-lessee will give its usual security package in favour of the intermediate lessor, who will on-assign that security in favour of the lenders, whilst also providing its own security package.

Key concerns in JOLCO transactions

Although JOLCOs are becoming increasingly commoditised given the breadth of their application, it is important to consider the individual characteristics of each JOLCO arrangement.

One key consideration is the lessee’s jurisdiction, which will impact a variety of elements of the transaction, including security arrangements and any restrictions on the lessee’s operations that might be required, given the regulatory regimes which might apply to lenders and the transactions into which they enter.

Another issue is the extent to which the obligations (generally payment-related but also positive covenants and representations given) of the parties under the lease and loan (and any intermediate lease, if applicable) can be made “back-to-back” in nature and, to the extent they are not “back-to-back”, how the risk of any mismatch is apportioned.

The lessee and any intermediate lessor will not want to shoulder excessive burdens that the lenders might require as terms of the financing. However, they might find that they have to if the lenders adopt a strict approach.

The question for intermediate lessors and lessees is how to mitigate this or find a compromise on other matters to lessen the load.

Looking forward

The benefits of JOLCOs to all participants in the transaction centre on the Japanese tax treatment of the underlying assets.

Should any fundamental changes in Japanese law be enacted, dramatic consequences on the benefits arising under JOLCO arrangements could result, thereby making them much less attractive to stakeholders.

Equally, a change in the Japanese economic environment could be a precursor to such changes in the legal and accounting treatment of these transactions or could, in itself, affect the appetite of investors for the product depending on alternative product offerings.

However, the JOLCO market currently continues to grow and is increasingly utilised by a wider range of participants, which suggests that it has a strong future ahead.

New IDERAs: Recent regulatory changes affecting the aviation finance industry

The Indonesian aviation sector continues to grow rapidly. With the majority of aircraft operated by Indonesian airlines being procured from foreign lessors or purchased with financing from foreign lenders, it is important for international stakeholders to be aware of the implications of the Regulation of Minister of Transportation No.52 of 2018 (New MOT Regulation).

What brought about the New MOT Regulation?

The Cape Town Convention is fully implemented and enforceable in Indonesia.

However, there was confusion surrounding Indonesia’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation’s (DGCA) treatment of Irrevocable Deregistration and Export Request Authorisations (IDERAs) until the New MOT Regulation was implemented in November 2018.

What is the Cape Town Convention?

The 2001 Cape Town Convention and its Aircraft Equipment Protocol are, together, known as the Cape Town Convention.

The Cape Town Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment is an international treaty intended to standardise transactions involving movable property by creating an international framework for the formation, registration – through an International Registry, protection and enforcement of certain international interests in airframes, aircraft, engines and helicopters.

What is an IDERA?

An IDERA is an authority document executed by the owner/operator of an aircraft, granting the authorised party or its certified designee the right to, following a default, deregister and export such aircraft from the aircraft registry in the state in which the aircraft is habitually registered.

How does the New MOT Regulation affect IDERAs?

The New MOT Regulation expressly permits an IDERA to be granted in favour of a creditor, i.e. a chargee in a security agreement, conditional seller in a title reservation agreement, or lessor in a lease agreement.

The DGCA will consider accepting registration of an IDERA, provided the following requirements are fulfilled:

- The DGCA’s new IDERA form is used.

- DGCA prescribed application forms, which may include a Certified Designee Deed of Appointment (CDDA) and Certified Designee Letter (CDL) are completed and submitted.

- The IDERA is in favour of a party other than the direct lessor, e.g. the financier.

- A summary of agreements written bilingually (Bahasa Indonesian and English), and signed by all parties involved in the arrangement is submitted,

- A Statement Letter on the DGCA’s prescribed form, signed by the aircraft operator and the party authorised under the IDERA, not to bring any legal action against the DGCA as a result of the IDERA registration.

If the IDERA is in favour of the direct lessor, the DGCA will accept a CDDA from the direct lessor in favour of any owner or financier, provided the IDERA and CDDA are submitted to the DGCA together with the CDL (which will be acknowledged by and registered with the DGCA).

Key considerations

It is important to note that if the DGCA, for whatever reason, refuses to record an IDERA or even if it simply takes a long time for the IDERA and any CDL to be recorded in Indonesia and that, in the meantime, an event of default occurs, the parties can produce any Deregistration Power of Attorney (DPOA), which would be in favour of the owner, and any Deregistration Consent Letter (DCL), which would be in favour of the financier, in an Indonesian court for the purposes of applying for a deregistration of the aircraft from the DGCA. The DPOA and DCL do not need to be registered in Indonesia for this purpose.